A Young Palestinian’s Diary

While many new books on Israel/Palestine pore over the conflict and its lack of resolution, the details of identity formation, the political trials and triumphs on each side, few books give the reader a heart-felt tug that can come from the voice of youth. Among works by and about Palestinians, many books that share individuals’ lives have thus far appeared in Arabic. Indeed, there has been an increase in the number of memoirs, autobiographies, and biographies, on both sides of the historical conflict, but few come from the pens of young people as they struggle to fulfill dreams of education, employment, and marriage to that right person.

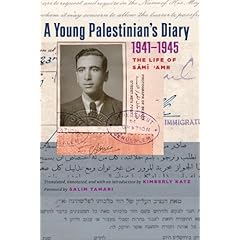

While many new books on Israel/Palestine pore over the conflict and its lack of resolution, the details of identity formation, the political trials and triumphs on each side, few books give the reader a heart-felt tug that can come from the voice of youth. Among works by and about Palestinians, many books that share individuals’ lives have thus far appeared in Arabic. Indeed, there has been an increase in the number of memoirs, autobiographies, and biographies, on both sides of the historical conflict, but few come from the pens of young people as they struggle to fulfill dreams of education, employment, and marriage to that right person. The publication of A Young Palestinian’s Diary, 1941-1945: The Life of Sami ‘Amr by the University of Texas Press (July, 2009) gives readers of English the opportunity to see the realities and challenges through the eyes of Sami, who wrote his diary while in his late teens and early twenties. Sami’s story is both a coming of age account and documentary evidence of the life of this particular youth (and perhaps many other young people during this period in Palestine and other parts of the globe) experiencing life and rule under the British mandate (1917-1920, military administration; 1920-1948 mandate government).

Sami left his home in Hebron at 17 years of age to find work and a place to live in the British mandate capital of Jerusalem. The vagaries of living alone in the city appear poignantly in the pages of Sami’s diary, as he shares his experiences of different rented rooms and flats, landlords and landladies, as well as the neighbors and co-workers whom he encountered daily. He was not always alone, as he sometimes shared a flat with a brother who at first worked with him, and later joined the British army. His brother Sa‘di’s experience in the military serves as a stark reminder of the complexities of the Palestinian Arab experience during the mandate period, just as it should remind researchers how little studied this aspect of Palestinian history during the British mandate is. His struggles with work, relationships and his future appear throughout revealing not only the difficulties of his life but also his perseverance through tough circumstances. In reading about Sami’s efforts to advance his studies, his work in different jobs connected to the British government in Palestine, and his travails in love, the reader becomes fully aware that his experience is the experience of youth almost everywhere: completing an education, finding a suitable job, and finding a life partner.

The backdrop for all of this is the cities of Palestine that Sami lived, worked, and traveled in: Hebron (his birthplace), Jerusalem (his workplace), Ramle (another place for work), Anabta, Jaffa, Nablus (where he visited family members), the beach, and the Nunqur valley (where he sought entertainment on his days off from work). The reader travels with this young man, grasping both his strong tie to his family and his strong tie to his homeland: Palestine. True to the history of the time period, Sami shares in the pages of his diary the diversity and pluralism that existed in Jerusalem, as the young man from Hebron interacted with mandate and military officials, locals girls (e.g. Greek, Jewish, Christian, Muslim) and others who add color and richness to the city and this period of history (including an Italian landlady who tried to seduce him!). It is a remarkable story, only made more remarkable by the fact that he documented it at the time and preserved it for over fifty years until his death in 1998.

Sami’s eldest son, Samir ‘Amr, came in possession of his father’s diary, and it is he who sought to have it published and asked me to work the original Arabic manuscript, which I translated and annotated. In addition I wrote an extensive introduction to the book, which will introduce the reader to the history and historiography of Palestine, as well as to the family and family history of Sami ‘Amr. Indeed, Samir’s enthusiasm for the project remained constant throughout the research and publication, as he facilitated access to his living family members, furnished photos for the books, and helped clarify a number of issues in my translation, which he reviewed for a final time before the book was published.

In the absence of a state, an official Palestinian historical narrative is challenging. At best it is scattered through the various remaining documents, photographs, and personal accounts that usually bear political and nationalist perspectives; at worst, such an official account is absent. Indeed, one might read Sami’s diary as a form of resistance, a statement of his (and Palestinian Arabs’) presence on the land that within five years after the completion of the diary would witness the dispossession of hundreds of thousands of Palestinians with the concomitant establishment of the state of Israel. In fact, Sami only briefly mentions politics; rather, it is his very personal dedication both to his family and to his home city and country that appears in the diary’s entries. His words are personal but in the very public arena in which the book’s publication has thrust them, readers of English now are able to share in his challenges, obstacles, and disappointments, just as they are able to participate in his triumphs, his hopes, and his joy.