Photographer Peter van Agtmael's Unsparing Images from Iraq and Afghanistan

In a recent column entitled "The Pictures of War You Aren't Supposed to See," esteemed correspondent Chris Hedges described the nature of modern war: "War is brutal and impersonal. It mocks the fantasy of individual heroism and the absurdity of utopian goals like democracy. In an instant, industrial warfare can kill dozens, even hundreds of people, who never see their attackers. The power of these industrial weapons is indiscriminate and staggering... The wounds, for those who survive, result in terrible burns, blindness, amputation and lifelong pain and trauma. No one returns the same from such warfare. And once these weapons are employed all talk of human rights is a farce."

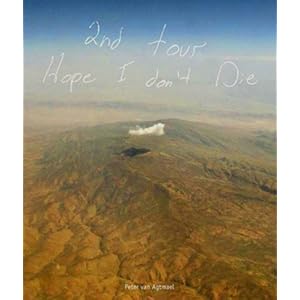

To help readers understand the toll of war, Hedges recommended two haunting books of photographs that "attempt to unmask war's savagery": Peter van Agtmael's 2nd Tour Hope I Don't Die and Lori Grinker's Afterwar: Veterans from a World in Conflict.

In 2nd Tour, Peter van Agtmael, 28, chronicles his tours as an embedded photographer with US troops in Iraq and Afghanistan from 2006 to 2008. He photographed night raids in Baghdad, war-torn Iraqi streets, the pain and chaos of a busy Baghdad emergency room, and firebases in Afghanistan, as well as wounded veterans and military funerals back in the States.

Van Agtmael's book has been acclaimed for its honesty, compassion and unflinching portrayal of war and its toll at home and abroad. His work has been compared to renowned photographers he admires, such as Don McCullin, Larry Burrows, Catherine Leroy, David Douglas Duncan, James Nachtwey, and Gilles Peress. The first edition of 2nd Tour has sold out, but the venerable photography collective Magnum is planning a second printing in the near future.

Van Agtmael began serious work in photography as a student at Yale. After graduation in 2003, he received a fellowship to live in China for a year and document the consequences of the Three Gorges Dam. In 2005, he covered the Asian Tsunami, then relocated to Johannesburg, South Africa, and covered sub-Saharan Africa. He began extensive work on U.S. wars as an embedded photographer with the military in 2006.

Van Agtmael has won numerous awards for his work, including the World Press Photo Award in 2007 for his work in Iraq. He again covered Afghanistan last fall, and this past January, his assignments ranged from a tour with actor Jeff Bridges to humanitarian relief efforts in Haiti and New Orleans.

Van Agtmael recently talked at length by phone about his photography and covering war from his family home in Maryland.

Robin Lindley: Were you interested in war photography as a child?

Peter van Agtmael: I was interested in war, especially World War II. I got into details like the Finnish planes in 1939, and how many machine guns they had. The interest in war led to photographs of cool tanks and airplanes. But when I saw what they did in stark human terms, it freaked me out. I was about 10 years old. I didn't lose interest in war, but lost interest in being a soldier.

The interest in history continued, and went well beyond war to the great civilizations. In college, I recognized that the great civilization now is my civilization. I started taking pictures my sophomore year and took to photography immediately. And I knew I wanted to cover these wars of America.

Lindley: How did you become an embedded photographer with the military?

Van Agtmael: I did it on my own. I just e-mailed the Army public affairs people in Baghdad and said I wanted to be embedded. It took a few weeks, and suddenly I was on a flight to Iraq.

Lindley: Did you have any special training or preparation?

Van Agtmael: I did a one-week course for photographers on how to operate effectively in a war zone. More important, instinctually I'm a cautious person and, before I do something, I think a lot about how to do it so I won't get hurt. My gut told me I was ready to go to Iraq after I spent a year in Africa.

And it was a leap of faith to go there. No matter how much you prepare, the way you get killed in Iraq is you just step in the wrong vehicle and it gets blown up. And sometimes it's the first vehicle in a convoy that gets blown up, and sometimes it's the second or the third or the fourth. When your number's up, your number's up.

Lindley: What was it like to arrive in Iraq?

Van Agtmael: I was confident I'd made the right choice, but freaked out too. When I flew in, it didn't feel like a war zone with raging fires and shooting everywhere. The fighting in Iraq and Afghanistan is very contained. The nature of these wars is that when things happen, it's very sudden. It doesn't feel like a war, then all of a sudden, you're in the thick of it.

Lindley: Did the first unit accept you?

Van Agtmael: I got along well with the soldiers in the unit, but at first I felt like a fish out of water. But slowly, as you share experiences, you get to know these people, and in war zones people are generally more open with their emotions.

Lindley: Did you have any censorship restrictions?

Van Agtmael: There were no real restrictions. I felt if I'm going to put myself at risk, I'm not going to cut any corners. I worked to a manic degree. I was going on a lot more patrols than most of the soldiers. I was full of the same kind of piss and vinegar of a new soldier eager to go out and prove himself.

Lindley: How did you feel about the night raids by soldiers where they broke into civilian houses?

Van Agtmael: I was pissed off on a lot of levels. It was complicated: my understanding and empathy for the people was growing, and at the same time, I saw them commit these terrible acts, and I wasn't sure why. I was thinking, rather naively, wouldn't it be great if democracy was brought to the Middle East [and] maybe this violence is a way to bring that democracy. I wanted to figure it out for myself, and that was a reason to witness it. You either drink the Kool-Aid, or become radicalized by these things, and I became radicalized.

Lindley: Your photographs capture the chaos of those raids. There's a picture of a young Iraqi after a soldier hit him in the face with a gun butt. Did that shock you?

Van Agtmael: That certainly shocked me. By then, I was taking angry photographs to show what was happening in its starkest, most straightforward reality. I was there about two months or so, and I got tired of it. I went home, and within a few weeks, I thought there was so much more I needed to do. I didn't want to transition from the war.

I was on a mission to have as many people as possible see these pictures. I worked for mainstream media sources like the New York Times. I believe in the role of the media, but I find that most publications very rarely want to give American a glimpse into the real, dirty, depraved core of the war.

Lindley: So you faced censorship by the media rather than the military?

Van Agtmael: Yes. There's questions about where the great pictures are from Iraq and Afghanistan, and whether the embed system is corrupting objective reporting. My conclusion and my colleagues is that the pictures are being taken, but they're not getting published, and that's a big shift from Vietnam where they showed the stark brutality of war.

The news is as much to provide entertainment as information and my guess is that the advertisers don't want bad news. Inevitably corporate America allows for these diverse news sources with the strength of the dollar, but it puts on serious limitations.

I did the book in the first place [because] I didn't feel that anything I had seen that had any meaning to me whatsoever or that defined my experiences was being seen by an American audience, and I was pissed off about that.

Lindley: How did you decide to go back to Iraq after these horrific night raids?

Van Agtmael: I don’t know how to explain it in a rational way. I thought this is what I needed to do with my life, no matter the risk to my life. I'm an idealistic person and believe in the value of bearing witness, and in human progress and evolution.

Lindley: Did you choose your assignment at the Baghdad emergency room?

Van Agtmael: I've always chosen. And the military wants to get the news out.

Lindley: The E.R. must have been much different than the field missions.

Van Agtmael: Yes. It was a lot of waiting, and then chaos, and you might see something that would change your life, and then it would be quiet again for many hours, then all hell would break loose again. When you're in the Green Zone in the E.R. you don't feel like you're in a war. It's surreal. You're not in danger, but you see the effects of something awful that happened.

Lindley: Was it difficult to work while physicians were treating seriously wounded patients?

Van Agtmael: Yes. But the doctors were interested in getting out these images of the brutality. I felt facilitated by the whole staff in the E.R.

Lindley: And you got to know some patients and visited them later in the U.S.

Van Agtmael: They [were on] various painkillers, but were conscious. As the doctors and nurses worked on them, I'd chat with them and try to distract them from what was going on. I wanted to be involved in a helpful way. It gave me some consolation, and it allowed me to make sure I had consent for the pictures.

Lindley: Your pictures of wounded soldiers are especially moving. One shows a soldier who was badly burnt and died shortly after you took the photo.

Van Agtmael: That was a terrible moment, and my life changed after that five minutes when he was on the table screaming. That memory lingered in my brain, close to the surface, for a very long time. Even writing the caption was difficult.

Lindley: Some of the memories must be very difficult for you.

Van Agtmael: It hit me later. After finishing the book, a lot faded away. Mostly I'm at peace with it. These things linger and screw with people's heads in the long term if they have some moral culpability. The soldiers are suffering more because they have questions about whether they did the right thing. I feel confident I did the right thing.

I was in a bad place after that second trip to Iraq. At this point, I accept that these things happened and I can only take pictures of it. That's my job. To be devastated on a personal level would be pointless because I couldn't do my job any more.

My intention is to do this for a very long time. You can't predict when something will screw with your head, but in the meantime, I'm doing well. I want to work with these wars as long as they last, but I don't have a strong interest in just covering wars. It's a good way to have a short and screwed up life.

Lindley: Do you think your pictures will prompt people to question war?

Van Agtmael: I think so. People end up at war through ignorance more than anything else. As a kid, I was deeply affected by seeing these realities without ambiguity, without any Hollywood veneer. I completely believe in that notion, and that's the reason for doing this photography in the first place. You don't necessarily change what's going on, but I do want the photographs to resonate and I take the long view with all of this.