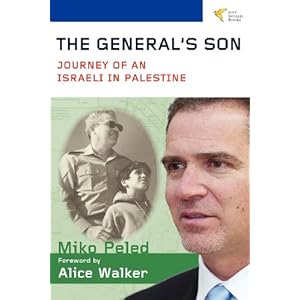

Murray Polner: Review of Miko Peled’s “The General’s Son: Journey of an Israeli in Palestine” (Just World Books, 2012)

Murray Polner is a regular book reviewer for the History News Network.

Just by having Alice Walker write the foreword, you know immediately what approach Miko Peled will take in The General’s Son. It was Walker who recently refused to allow an Israeli book publisher to issue a Hebrew language translation of her Pulitzer Prize novel, The Color Purple. In doing so, she compared Israeli treatment of Palestinians under occupation with South African apartheid. In her statement withholding permission to publish her novel, she said, “I grew up under American apartheid and this [treatment of Palestinians] was far worse.”

Just by having Alice Walker write the foreword, you know immediately what approach Miko Peled will take in The General’s Son. It was Walker who recently refused to allow an Israeli book publisher to issue a Hebrew language translation of her Pulitzer Prize novel, The Color Purple. In doing so, she compared Israeli treatment of Palestinians under occupation with South African apartheid. In her statement withholding permission to publish her novel, she said, “I grew up under American apartheid and this [treatment of Palestinians] was far worse.”

Whether the reader agrees in whole or in part or not at all, Miko Peled’s idealistic and passionate memoir reflects in part those Jews everywhere who have grown increasingly uncomfortable with the harsh Israeli occupation and continuing colonization of the West Bank, captured from Jordan during the 1967 war. “How did we reach this point?” asked a distressed David Shulman, an Israeli dove who teaches at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem and is active in Ta’ayush Arab-Jewish Partnership. How indeed?

What Peled sets out to do is reintroduce Matti Peled, his highly respected Israeli general and father who became a fearless advocate for an end to the occupation and establishing a viable and independent Palestinian nation. Miko, the son, tries hard, though not always successfully, to explain why his father -- and his mother, whose own father was Abraham Katznelson, a legendary figure in Zionist history -- dramatically changed their views and opposed their country’s policies toward Palestinians.

Matti Peled was born in Haifa in 1923, resisted the British Mandate as a member of the Palmach, a Jewish paramilitary militia and opposed the Jewish extremists and terrorists in the Irgun and the Stern Gang. He later served in the IDF rising to the rank of general. Always a believer in Zionism as a national liberation movement and still a hawk, in 1967 he played a crucial role in the so-called Six-Day War, when Israel crushed Egypt and for a while he backed the U.S. invasion of Vietnam, even visiting American forces there at the Pentagon’s invitation. At the time, bogged down in a dirty and unwinnable war, many in the U.S. military tended to think of the Israelis as super-warriors. For much of his life, then, he was oblivious to Palestinians who had lost their homes and lands.

Miko thinks his father’s brief tenure as military head of Gaza in the '50s might have begun his transformation. There, in that deeply troubled, teeming speck of territory now governed by the democratically-elected Hamas, he was taken aback by the absolute power he held over a people whose language he could neither speak nor a culture about which he was ignorant. He then set out to learn Arabic and later he became professor of Arab literature at Tel Aviv University, earned a Ph.D. at UCLA, and wrote a dissertation about the gifted Egyptian writer Naguib Mahfouz.

Increasingly unconventional, genuinely interested in the intractable Israeli-Palestinian divide, he began supporting Israeli and Palestinian peace groups, working closely with Israeli peaceniks Amos Keinan, Aryeh Eliav, and Uri Avnery, and helped form Gush Shalom, the Israeli peace group still in existence. Along the way, together with Avnery and several non-Jews, he was elected to the Knesset under the flag of the Progressive List for Peace, which soon vanished, as do most small sectarian Israeli political parties.

Even so, Miko says he is always asked, “What made your father change?” He really can’t offer specific reasons though he points to things he believed transformed his father from hawk to dove. Miko speculates that reported shootings of Palestinian civilians and torture of prisoners must have deeply disturbed his father. So it was no surprise that when Israel invaded Lebanon in 1982, the general urged Israeli soldiers not to participate and he was deeply sympathetic to Yesh Gvul, an organization of Israeli soldiers who refused to fight. What they asserted was a war of choice not defense, a position soon taken by hundreds of thousands of protesting Israelis in Tel Aviv.

Miko also recalls his father’s speech at a synagogue in San Francisco, when he urged the U.S. to stop peddling Israel weapons and above all stop sending it money. “Receiving free money, money you have not earned and for which you do not have to work, is plain and simply corrupting.” He added that U.S. weapons were being used against the Palestinians.

In 1997, two years after the general died, his thirteen-year-old granddaughter, Smadar, Miko’s sister’s child, was murdered by a Palestinian suicide bomber on a Jerusalem street. The resulting shock led some family members, especially the girl’s father and Miko’s brother-in-law and close friend, to condemn Palestinian terror. Others in their circle wondered whether any cause, however justifiable, was worth the death of a child. A grieving Miko, an IDF veteran, was then as now living in San Diego with his wife, where he was teaching judo, and their life in escapist southern California “did not include any Israeli or even American-Jewish friends.”

He sought solace after the murdered child’s parents encountered the Orthodox Israeli Itzhak Frankenthal. His brother-in-law described his first sight of him: “a large and impressive man with a knitted kippah [skullcap] on his head” whose own son had been killed by Hamas thugs in 1974. Frankenthal had visited Smadar’s home during shiva, the Jewish ritual for the dead, leaving her father deeply upset. To Frankenthal he protested, “How dare you walk into the home of someone who just lost a child and talk about peace and reconciliation. Where do you get the nerve to do that?” Frankenthal said he had come to invite the brokenhearted couple to meetings of his Bereaved Families Forum, comprised of Palestinian and Jewish families who had lost their children in the endless violence yet still believed in peace and reconciliation. In distant San Diego, eager to find an outlet for his own grief, Miko organized the Wheelchair Foundation which offers free wheelchairs for Israelis and Palestinians victimized by the mutual bloodshed.

Even so, visiting Israel fairly regularly he found many unsympathetic to his dovish views. He had turned against the notion of two independent states existing side by side instead supporting a single state with all citizens equal. This was an echo of the past, as when Judah Magnes, the first Chancellor of the Hebrew University and Martin Buber the eminent philosopher, among other Zionists, had urged the same approach in the thirties, an approach which then and now is dismissed by most Jews and Palestinians.

Miko, now a full-throated dissident proponent of Palestinian rights, visited Bil’in, an Arab village which for years has been opposing the occupation without violence. He supports sanctions and boycotts against Israel. He calls the IDF a “terrorist organization” and urges young Israelis to refuse to serve, which most youngsters, even liberal-minded ones who loathe the way Palestinians are treated, find it hard to contemplate, let alone practice. He quotes an acute challenge directed at him, “Are you suggesting that we refuse to serve in the same army that your father helped to build? The first Jewish armed force to protect Jews in over two thousand years?”

Even so, he is outraged when he contemplates the never-ending rationalizations that justify the killing of Palestinian civilians while condemning the killing of Israeli civilians. “Struggling to end the segregation and create a secular democracy where two nations live as equals, while difficult is not naïve, nor is it utopian,” he insists. “How,” he asks, reflecting his late father, “did Israelis turn away so completely from the values I thought we all held dear?”