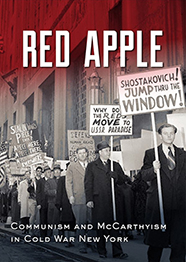

Review of Phillip Deery's "Red Apple: Communism and McCarthyism in Cold War New York"

In June 1950, Edward Barsky went to jail. So did ten other members

of the board of the Joint Anti-Fascist Refugee Committee (JAFRC).

Their crime? They refused to relinquish to the House Committee on

Un-American Activities (HUAC) membership and other lists of their

organization, which had been dedicated since its founding in 1942 to

helping European anti-fascists in hiding and exile. This act of

defiance by Barsky and his JAFRC colleagues was heroic and

constitutionally justified, as the United States Supreme Court

eventually confirmed in a case protecting NAACP membership lists from

scrutiny by white supremacist state governments: According to the

Court, the threat of publicity and reprisal compromised the right of

political association. In the Barsky case that reprisal could be

deadly. Among the names on JAFRC lists were those of former Spanish

Loyalists still hiding out in Spain and elsewhere across Europe;

exposure would potentially put them in the hands of Franco’s brutal

secret police.

In June 1950, Edward Barsky went to jail. So did ten other members

of the board of the Joint Anti-Fascist Refugee Committee (JAFRC).

Their crime? They refused to relinquish to the House Committee on

Un-American Activities (HUAC) membership and other lists of their

organization, which had been dedicated since its founding in 1942 to

helping European anti-fascists in hiding and exile. This act of

defiance by Barsky and his JAFRC colleagues was heroic and

constitutionally justified, as the United States Supreme Court

eventually confirmed in a case protecting NAACP membership lists from

scrutiny by white supremacist state governments: According to the

Court, the threat of publicity and reprisal compromised the right of

political association. In the Barsky case that reprisal could be

deadly. Among the names on JAFRC lists were those of former Spanish

Loyalists still hiding out in Spain and elsewhere across Europe;

exposure would potentially put them in the hands of Franco’s brutal

secret police.

But until the Court decided the NAACP case in 1958, HUAC had its way. And what, after all, did the committee want with that list or any of the other membership lists it subpoenaed in the long nightmare we call “McCarthyism?” As this fine little book by Australian historian Phillip Deery makes clear, reprisal and intimidation were the whole point. Deery traces the campaign against JAFRC through the lives of five of its members, most of them relatively unknown in the history of McCarthyism. Their stories, heroic, tragic and painful, are well worth reading.

Barsky and the JAFRC’s ordeal began in 1945, when a newly reconstituted HUAC launched their first post-war inquisition of the American left. That date is important. This was the “first flexing of political muscle by HUAC,” Deery writes. And its successful attack on JAFRC established the “framework…for future congressional inquisitions that were to become such an emblematic feature of McCarthyism.” Moreover, the fact that the assault on JAFRC “commenced very early in the postwar period,” underscores an important truth about McCarthyism: It started a good two years before the beginning of the Cold War. So, as a new generation of Cold War historians is beginning to make clear, the Red Scare was not triggered by an unmistakable Soviet menace against the United States. That threat could not be plausibly identified until at least 1947. By that year, Barsky and his associates had already been convicted in a federal court. Among them were two New York University professors, Edwin Berry Burgum and Lyman Bradley, as well as the novelist Howard Fast and JAFRC executive secretary, Helen Bryan, a Quaker activist. Only some of them were Communists. All of them spent time in jail.

Nor did their persecutions end there. Barsky, a physician and a Communist, heroically ran field hospitals during the Spanish Civil War (Ernest Hemingway called him “a saint”); yet, he had his medical license suspended while in jail for reasons undisclosed but nonetheless clearly retaliatory. The United States Supreme Court upheld that decision in 1954. In his dissent, Justice William O. Douglas wrote “nothing in a man’s political beliefs disables him from setting bones or removing appendixes…. When a doctor cannot save lives in America because he is opposed to Franco in Spain, it is time to call a halt and look critically at the neurosis that has possessed us.”

The nightmare continued as well for Howard Fast, who in 1945 was at the height of his career. Citizen Tom Paine (1943), his most successful novel to date, had been distributed by the military to American servicemen and to liberated nations by the Office of War Information. It was on the approved list of novels for New York City’s public school libraries. After his conviction, Fast “struggled to be read.” His most famous work, Spartacus, finished after Fast got out of jail in 1951, could not find a publisher thanks to concerted lobbying with publishing houses by historian Arthur Schlesinger, Jr. and the rabidly McCarthyite magazine Counterattack. Ultimately, Fast had to privately finance the novel’s publication. And it suffered, like the rest of Fast’s books in the 1950s, what novelist and friend Albert Maltz called a “savage and sweeping” boycott by American reviewers. Deery methodically chronicles the collapse of Fast’s prospects up to his public repudiation of the Communist Party in 1957, which came largely in response to the party’s increasingly doctrinaire culture, Soviet anti-Semitism and Khrushchev’s revelations at the 20th party congress the previous year. Yet as Deery makes clear, Fast’s apostasy also followed from his forced isolation and the damage done to his career by the HUAC inquisition.

This is an extremely well documented, lucidly written study, using personal correspondence, Party records and other archival sources amplified by newly declassified FBI files. Throughout, Deery impresses upon the reader the personal costs of McCarthyism, as he tries to get at the “largely hidden” history of “that pervading sense of fear and anxiety…which was experienced privately and silently” by many Communists and non-Communists in the late 40s and 50s. He succeeds in showing in these five sketches “how the phenomenon of McCarthyism wrecked the lives of a group of American citizens” and how “living on the left during a time of apparent national crisis can test resilience, destroy careers, and endanger liberties.” The experience of Helen Bryan was typical. HUAC and the FBI insisted she was a “higher echelon” Communist Party member, only to admit years later that they were wrong. But the damage, to her life and her career, had been done.

Yet, while Deery plays to our understandable sympathy for these destroyed lives, he does so at the expense of deepening our understanding of McCarthyism’s effects on American politics and culture. We still ask, what exactly was that neurosis that possessed us? And how did it change us? Deery focuses on violations of rights and personal injury. That is commendable, especially given the blithe dismissal of such things by some Cold War historians preoccupied with the tiny proportion of former Communists (a few hundred out of tens of thousands) who spied for the Soviet Union. Thus, Deery is absolutely right that “…we must delineate the clandestine ‘nonlegal’ party apparatus from the open, daily struggles waged by communists for social justice and ‘a better world.’”

Beyond the necessary discussion of rights and personal damages, however, lie even more pressing questions about politics and power that tend to get obscured in these kinds of studies. Deery exposes a systematic process of intimidation and reprisal that served the very clear purpose of driving present and future adherents and allies away from the Communist Party while depleting the broader institutional culture of the left. Its effect was to destroy those institutions (what conservatives and liberals contemptuously call “front groups”) and banish die-hard believers from public and professional life. Deery makes passing reference to those repercussions, for instance in the academy, but he consistently turns our attention back to the personal. That may be a safe standpoint from which to criticize McCarthyism, but isn’t it time we moved to riskier positions? While we should never forget the damage done to individuals by the Red Scare, more important was its effect on American political culture. With hindsight, we should now be able to say that McCarthyism politically impoverished us all. But, generally speaking, we can’t. That is a problem – a symptom, I would think, of the impoverishment itself.