Oscars: Real History Is Far More Intriguing than Reel History

It’s Oscar time once again on Sunday and the controversy over history in films exceeds that of the gowns worn by all the glamourous women on the red carpet.

Several Oscar Best Picture nominees have been lashed by critics for their misguided history. The character of Alan Turing in The Imitation Game was criticized by many as too strident, unlike the real Turing. CNN aired a news piece in which the veracity of American Sniper author Chris Kyle, the hero of the book and movie, was attacked. Selma has been flogged over its muddled history for months.

The movie colony is not alone. Plays and television shows have been charged with historical misinformation for years, too.

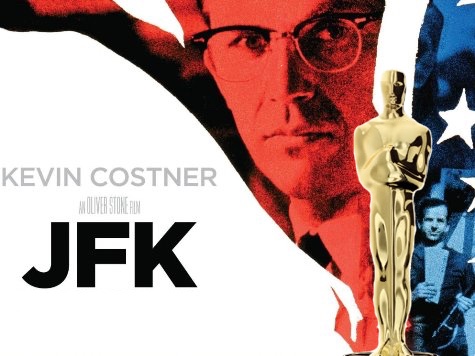

The three Oscar nominee movies are just the latest in a long line of very good films that have been chastised for distorting history. The slanting of history in the arts goes all the way back to 1851, when artist Emmanuel Leutze painted the famous portrait of George Washington standing up in his boat as he and his men crossed the Delaware River on Christmas night, 1776 (the General was actually sitting down). In 1915, writer Thomas Dixon Jr. and film director D.W. Griffith twisted history in the racially horrific Birth of a Nation. Remember the tangled story of boxer Hurricane Carter in Hurricane? The crazy, widespread conspiracies in Oliver Stone’s JFK? Just about any of the 1950s western television series? And just last week, critics in Poland lambasted film director Pawel Pawlikowski’s foreign language Oscar nominee Ida because the film did not emphasize that it was the Nazis, not the Polish government, that ran the Holocaust in Poland during World War II that took the lives of millions of Jews.

This is not new. It has been going on for generations. Do you remember the 1950s film The Bridge on the River Kwai? Not only did the film producers savage the history of British soldiers in Burma in World War II, but presented a movie in which the bridge over the river Kwai wasn’t even over the River Kwai.

The director of the television mini-series George Wallace shot a scene, that he admitted was made up, of an African-American worker in Wallace’s mansion considering murdering him with an ice pick. In the 2000 film U-571, an American submarine captures an enigma (intelligence) machine from a German U-boat. Well, it was really a British team that did that. Everybody in Britain was so furious that Parliament actually condemned the film,

How about Kevin Costner’s epic revision of history in Thirteen Days, the story of the Cuban missile crisis as seen through the eyes of White House aide Ken O’Donnell. The real crisis was powerful drama and did not need Costner’s new look at it. You can’t find a much more dramatic story than the threat of nuclear annihilation. Why twist it to make O’Donnell, and not JFK, the hero? George S. Patton pulling out his pearl handled revolvers in North Africa and firing at attacking German planes in Patton? Never happened. Wasn’t the heroic Patton, with all his flaws, a good enough story?

The moguls in Hollywood take no blame. They beat their chests and roar that “it’s just a movie,” to cover up their assassination on history. Another of their defenses: we have to make an engaging film and real history is not that engaging. A third defense: You want an authentic movie about World War II: we’ll give you a movie, all right but its four years long. And finally: hey, we just changed things a little but had the spirit of the true story.

Well, the spirit is just not the same. Lyndon Johnson was a hero in the Civil Rights fight, along with Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and numerous other white and black men and women. Ava DuVernay, the director of Selma, not only dismissed him, but presented LBJ as a Presidential ogre intent on derailing the movement. She then said, as they all do, that’s it’s just a movie, just one interpretation of events.

Now, Hollywood has made transgressions that you can forgive, such as the real Bonnie and Clyde looking nothing like glamourous Warren Beatty and Faye Dunaway, or the kindly, loving portrait of Robert Stroud, the Birdman of Alcatraz, who was really a psychotic. What real life characters had the glamor of Errol Flynn or Johnny Depp? How many World War II soldiers had the swagger of John Wayne? We can forgive that. The overt revision of history, as was done in Selma, cannot be ignored, though.

The big problem is that Americans don’t read much anymore and are getting their history lessons from movies. Historian Simon Schama wrote that the screenwriters are now the ones who decide what a nation’s history is, not the historians.

Kim Peirce, the director of Boys Don’t Cry (1999), is a shining example of that. Her drama was a film charged with inaccuracies. She fumed that “You can change facts. You can change characters. You can change everything in search of the truth.” Huh?

A long string of big, colorful, dramatic events make up the American story from D-Day to Selma to San Juan Hill to Gettysburg to lynchings to murders to injustices against minorities and the oppression of women. Hollywood can produce movies about all of them and stick to the truth. The truth of them is far more intriguing than Hollywood’s perception of history, quickly written besides some pool. You need to embellish the larger than life story of Lyndon Johnson? Of Martin Luther king Jr.? Come on.

Media moguls shout that doing that is too lengthy a process, too complicated, too costly. It’s not.

The easiest way for Hollywood to solve its problems with history is, as I have written before for HNN, just add extra thirty seconds of dialogue. The screenwriters should have one character turn to another and tell the true history of the event. Thirty seconds, that’s all. Or, as Hollywood did back in the 1930s, run a scroll at the start of the picture to say something like: “This is a fictional movie set in Poland, where the Nazis conducted the Holocaust after overrunning the country.” Problem solved.

It works, and works well. Look at the success, in glowing reviews, Oscars and box office tallies, of Lincoln, Steven Spielberg’s masterful portrait of the sixteenth President. He gave the country a terrific look at the political genius of Lincoln, warts and all, plus his feisty wife and angry son. It was gripping and it was real. It was far better than the dozens of heroic, syrupy stories about Lincoln that have cluttered the screen since the birth of film at the turn of the century. The truth of Lincoln was much better than the fiction.

These are all suggestions to obtain better films and also get Hollywood, the theater and television off the hook. Audiences love history, but they want accurate history.

Will the moguls listen? Of course not.

I know what we’ll see next on the silver screen: Joe Frazier knocks out Muhammad Ali in the “thriller in Manila.” Ali then looks into the camera and says he lost because he was out of shape after his two tours of duty with the U.S. Army in the Vietnam War.

Or, after that, Tom Cruise as Barrack Obama?