Spike Lee’s Da 5 Bloods: How Bad is It?

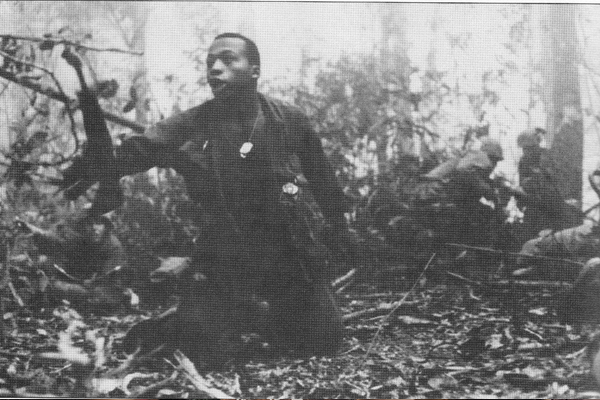

“Awful” is not the most thoughtful way to begin a film review. But why mince words? The film’s “bloods” are four black Americans who have returned to Viet Nam to recover the remains of a fifth, their buddy Norman. If you took the storylines of Frances Ford Coppola’s 1979 Apocalypse Now out of Bloods – yes, they even go upriver to strains of Wagner’s Ride of the Valkyries! – there is little originality left for filmmaker Spike Lee to claim; even its subplot of the four’s search for a buried chest of gold bars is plagiarized from 1999’s forgettable Gulf War adventure Three Kings.

Bloods trots out every caricature of Viet Nam War figures that you can imagine, beginning with American veterans of the war. The image of traumatized veterans was a Hollywood staple even before PTSD was canonized in the 1980 DSM. The utility of the victim-veteran as a metaphor for the America victimized by the war made it political and filmic catnip from Ronald Reagan’s “Morning in America” years to Donald Trump’s campaign to “Make America Great Again.” You might think Spike Lee could leave it alone but no: when fireworks are thrown outside a bar in Ho Chi Minh City, all five “hit the deck.” Later, one of them randomly claims “we all have PTSD,” while still later another says, “We’re all broken.”

But Viet Nam veterans were not all broken. Most returned quietly to their workplaces and schools like veterans of any other generation. Many others, politicized and empowered by their wartime experience, joined the antiwar movement. One of those, Chuck Searcy, returned to Viet Nam and founded Project Renew devoted to finding and defusing unexploded ordinance left behind by the American military in Quang Tri Province. Searcy is white. Maybe Lee has his bloods connecting with Searcy and redefining their mission—instead of searching for buried treasure, they search for buried landmines? Guess again.

Lee’s troop meets up with a group of backpackers in-country to do Project Renew-type work. The group’s leader is a whiter-than-white twenty-something woman, a scion of wealth reaped from what had been French Indochina—a riff from the 2001 Apocalypse Now Redux—who is irresistible to a son of one of the bloods who has (somehow, inexplicably) arrived in the jungle from Morehouse College.

Bloods’ racial clichés are the film’s strongest through line. The bloods come across as foulmouthed and uninformed about the war as they probably were when they were sent to fight it; the veteran-father of the Morehouse College man is an absent presence in his son’s life; and with the exception of Otis, who takes time in Ho Chi Minh City to find the daughter he fathered back in the day, the bloods are as disdainful of the Vietnamese as many GIs were at the time. And the Vietnamese characters fit stereotypes too: some paramilitary guys looking like the hapless losers seen in most American movies (check); the one woman, a wartime prostitute (check).

This awful movie is also dangerous. With one blood wearing a MAGA hat, the loss of the war is attributed to home-front betrayal—upon return, we were called “baby killers,” says one of the four. Republicans have been on a half-century campaign to avenge the treachery of the anti-war left, as they see it, and now is not the time to give credence to Trumpian revanchism as a promising course for Black Americans—or anyone.

The one good reason for seeing Da 5 Bloods is to credential your advice to others that they don’t.