When Did America Stop Being Great?

My formative experience of America came during this country’s great summertime of resurgence. It was 1984, I was sixteen years old, and I had flown into Los Angeles on the eve of the Olympics. For the next six weeks, I watched, wide-eyed, as the long national nightmare of Vietnam, Watergate and the Iranian hostage crisis was brought to an end by a modern-day gold-rush.

A multi-racial team of US athletes, led by the likes of Carl Lewis, Mary Lou Retton, Michael Jordan and Greg Louganis, completely dominated the medal table. Team USA even performed well in some of the more obscure events - a calorific boon for customers of McDonalds, which ran a scratch-card promotion, planned presumably before the Soviet boycott, offering Big Macs, fries and Cokes when Americans won gold, silver or bronze. With the thumping chant of “USA, USA” echoing from coast to coast, it was hard, even as a visiting outsider, not to be swept up in this torrent of patriotism.

Later that year, of course, Ronald Reagan surfed this red, white and blue wave to a second term in the White House, winning 49 out of 50 of states. For millions of his supporters, many of them lifelong Democrats, truly it felt like morning again in America, the sunny slogan of his re-election campaign.

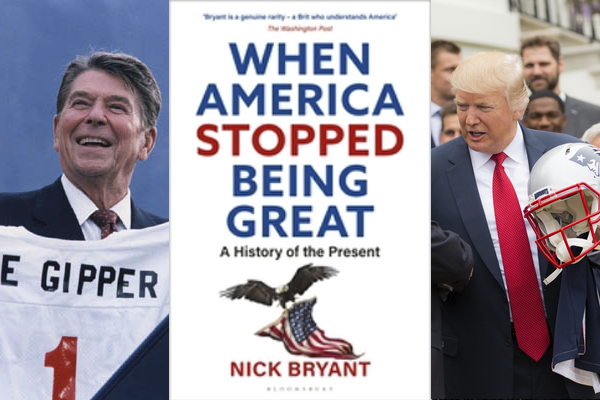

My new book, When America Stopped Being Great: A History of the Present, began as a quest for understanding. How had the United States gone from the self-confidence and swagger I experienced in the Reagan years to the American carnage of Donald Trump’s dystopian inaugural address? What had turned this country into a place of such chronic disunion, shared land occupied by warring political tribes?

Then, as I was writing it, further questions arose, which came under the same rubric. Why was this superpower so vulnerable to the viral onslaught of COVID-19? How had we arrived at the point where an insurrectionary mob could storm the US Capitol, violently seeking to overturn a presidential election in which Joe Biden had so obviously emerged the victor?

Like the unexpected victory of Donald Trump four years earlier, the botched response to the coronavirus outbreak and the brazen attack on the US democracy were culminating moments. They could not be written off as historical accidents or aberrations. Arguably, they had become historically inescapable.

How had this come to pass?

In locating the origins of this troubled present, we could reach back to the earliest days of the new Republic. “1776,” chanted the mob of MAGA diehards who invaded Capitol Hill, fervently believing they were acting in the spirit of the Revolutionary War. We could revisit the Constitutional Convention and the deliberations that produced the Electoral College, a relic of the Eighteenth Century that could never be described as the Founding Father’s finest work.

To understand America’s inherent contradictions, we could consider how the author of the Declaration of Independence could write that “all men are created equal” while also penning a pseudo-scientific treatise outlining what Thomas Jefferson believed was the biological inferiority of slaves. Or we could journey to the battlefields of the American Civil War – Fort Sumter, Antietam, Manassas, Gettysburg – to be reminded of how division has long been this country’s default setting.

Instead, however, I have retraced the steps of my own American journeys: as an impressionable teenager during the Reagan era; as a student in the Nineties conducting research into the struggle for Black equality; as a fresh-faced foreign correspondent dispatched to Washington to cover the impeachment of Bill Clinton. Witnessing his Senate trial, I felt sure it would be a once-in-lifetime event. But afterwards those kind of mega-stories came thick and fast: the disputed 2000 election, the attacks of September 11th, the war in Iraq, the Great Recession, the election of Barack Obama and presidency of Donald Trump, with its back-to-back impeachments.

Part history, part memoir, my book describes the role of each successive president in paving the way for Donald Trump – and, yes, they all contributed to his rise. Reagan, who was the first commander-in-chief since Dwight D. Eisenhower to complete two full terms, elevated the presidency while at the same time dumbing it down.

After the showmanship of The Gipper, George Herbert Walker Bush demonstrated the value of a less theatrical presidency, but this moderate Republican failed to halt the rightward lurch of the conservative movement. Radicals, led by Newt Gingrich, snuffed out his thousand points of light. The Baby Boomers, who had cut their political teeth during the culture wars of the Sixties, usurped the Greatest Generation, whose belief in patriotic bipartisanship was forged during the Second World War.

Bill Clinton may indeed have built a bridge to the 21st Century, but for much of Middle America it felt more like a bypass. And though he presided over a period of peace and prosperity, the Nineties were pregnant with so many of the problems encountered in the new millennium: the financial meltdown of the subprime crisis, the unchecked power of Big Tech, the problem of mass incarceration.

George W. Bush, by pursuing his war on terror in such a polarizing way, failed to seize the opportunity presented by the calamity of 9/11 to reunify an ever more fractious nation. Like his father, he also failed to steer the conservative movement in a more compassionate direction.

Barack Obama helped stave off a financial meltdown when he first took office in the midst of the Great Recession, but during his eight years in office he struggled to soothe the fears of blue-collar Americans who felt like castaways in a globalized and digitized economy. His presence in the White House, rather than closing the country’s racial rift, fuelled the rise of white nationalism and the presidential candidacy of the untitled leader of the birther movement.

And there are so many more milestones and waystations on the path to polarization.

The political success of Donald Trump should not have taken us all by such surprise. So many trend-lines – political, economic, racial, cultural, spiritual and technological - converged and culminated in his presidency. As the 2020 election underscored – a contest, remember, in which he won 25 states and amassed more than 74 million votes – his presidency was not some American aberration. He became the figurehead for much of this country, and remains so even after his role in inciting his moshpit of MAGA diehards on January 6th.

Just as few weeks ago, I was on the inaugural stand in Washington, just as I had been four years earlier, and listened to America’s 46th president, Joe Biden, make his plea for national healing. “We must end this uncivil war,” he said, in one of the more searing lines of his speech. Alas, the disturbing conclusion I reach in When America Stopped Being Great is that genuine national unification may now be impossible to achieve. The United States is riven with so many unbridgeable divides. Its very name has become a misnomer.

Travelling this vast land, I struggle to identify where politically, philosophically or spiritually it will find common ground. Not in the guns debate. Not in the abortion debate. Not in the healthcare debate. Not at weddings, where more than a third of Republicans and almost half of Democrats say they would be unhappy if their children married a partner from the other party, compared to 5 percent in 1960. Not in the singing of the national anthem at American football games. Not in the debate over the country’s history, and how it should be memorialized.

Few, if any, national events, are politically benign, ideologically neutral or detached from the culture wars. No longer are there demilitarized zones in US politics. It seems that everything is contested. Even the most rudimentary of facts. Even the simplest of protections, like the facemask. Even the most clear-cut of presidential elections.

After talking so much this century about the emergence of a post-America world, I fear we are living in a post-America America. The land that I fell in love with during that summertime of resurgence has entered a bleaker season.