Top 5 Myths About Christmas

Click here to see articles about the holiday published across the Internet.

#1 Myth

Retailers Have Ruined Christmas By Commercializing It

Until retailers began to see in Christmas the opportunity to market their merchandise the holiday attracted little of the attention it does now. It was retailers who made Christmas exciting. It was they who turned Santa Claus into a national icon. Montgomery Ward gave us Rudolf the red-nosed reindeer. Coca-Cola helped popularize the smiling Santa. Retailers discovered the commercial possibilities of Christmas after the Civil War. Only then did newspapers regularly begin to feature advertising sales associated with the holiday.

Retailers helped establish Christmas as an American tradition by persuading Protestants to overcome centuries of hostility to the holiday, which had long been identified as a popish import. The leaders of the Massachusetts Bay Colony so disdained Christmas that in 1659 they passed a law prohibiting the public celebration of the holiday, punishing"anybody who is found observing [it], by abstinence from labor, feasting, or any other way." The law was repealed 25 years later, but the prejudice against Christmas remained strong. Judge Samuel Sewall was delighted to be able to report in his diary in 1685 that he did not see a single person celebrating the holiday.

#2 Myth

Christmas Cards Are a Venerable Tradition

Yes, Virginia, Christmas cards are venerable. But it was the Victorian businessman who made the Christmas card an American tradition. Before the middle of the 19th century Americans simply did not send holiday greeting cards at Christmas.

#3 Myth

Clement Moore Wrote the Poem,"The Night Before Christmas"

Several years ago Vassar professor and professional debunker Don Foster concluded that Moore did not write the famous 1822 poem with which he is so identified. Foster claimed, according to an account in the New York Times in 2000, that the poem's"spirit and style are starkly at odds with the body of Moore's other writings." Foster speculated that the poem was actually written by Henry Livingston, Jr., an author from Poughkeepsie (where Vassar happens to be located).

The story made a big splash in the newspapers. It was then promptly forgotten. The same cannot be said of the poem.

#4 Myth

Christmas Trees Are Traditional

The Christmas tree first made its appearance in America in the middle of the 18th century, thanks to German immigrants. But a hundred years later it was still rare. In 1851 a Cleveland, Ohio reverend who had recently emigrated from Germany put up a Christmas tree in his local church. He was roundly condemned. Nobody before had ever put up a Christmas tree in an American church. Victorians in the latter half of the 19th century slowly began adopting the German tradition, but the Christmas tree remained controversial. In the 1880s the New York Times editorialized against the Christmas tree. When Teddy Roosevelt became president he denounced the practice of cutting down trees for Christmas. Good conservationist that he was, he declared the practice a waste of timber.

#5 Myth

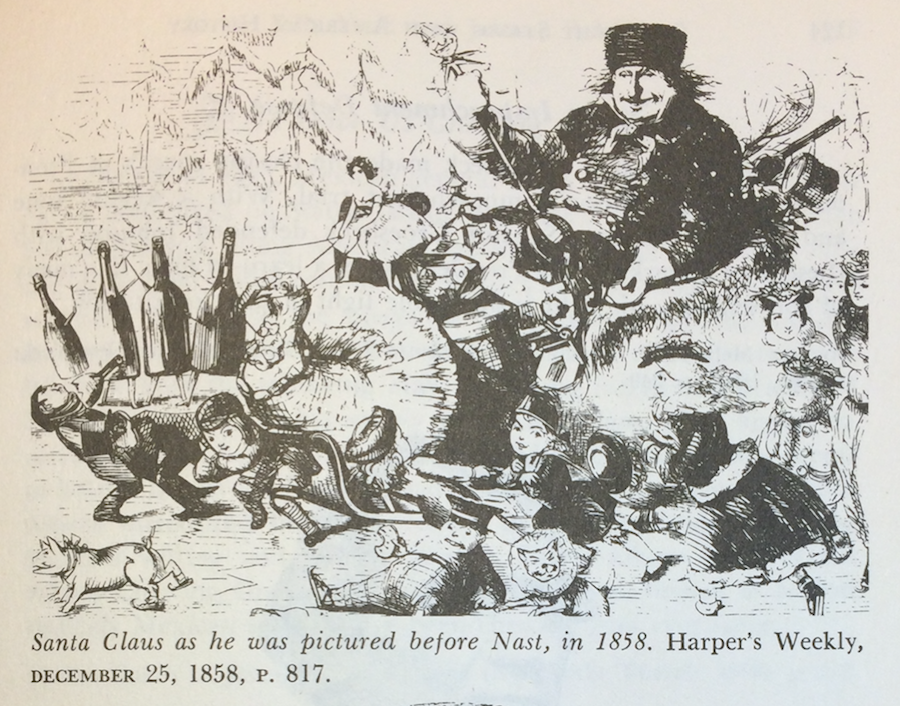

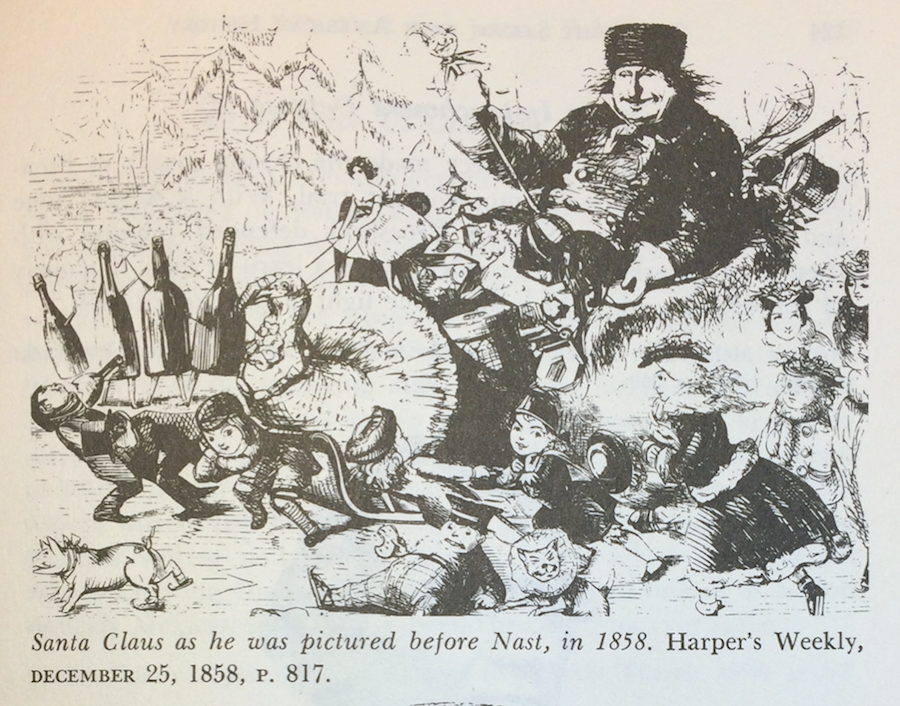

Santa Was Always Fat and Jolly

Whether he was a Dutch creation, as so many believe, is, according to scholar Eric C. Wolf, doubtful."There is no evidence," says Wolf,"that the Santa Claus myth existed in New Amsterdam, or for a century after English occupation." To be sure, Santa is loosely based on the European figure, St. Nick, the fourth century Bishop of Demre, Turkey, who was said to have carried a sack full of toys for children. But it was only after the Revolution, when writers began inventing American traditions, that Santa suddenly achieved broad popularity. The myth was slow to build. Not until 1821 was Santa seen flying in the sky behind a pack of reindeer. Only in 1837 do we find evidence that he arrived in American homes via the chimney. And not until the Civil War did Santa look the way we imagine him. In colonial days he was often described as thin and beardless. In 1809 Washington Irving imagined Santa as a bulky man who smoked a pipe and wore a Dutch broad-brimmed hat and baggy breeches. Later, Santa was depicted as a fat man with brown hair and a big smile. Then in 1863 Thomas Nast gave us our modern idea of Santa Claus, as a jolly fat man with a flowing white beard dressed in a red suit. Here it is: