Power Chords of Freedom

Much has been made over the years of the “revolutionary” power of rock music, particularly in 1960s America. What anti-war scene would be complete without images of rockers and (presumably) drugged-out hippies swaying in the wind? The notion that rock music marched in the forefront of the anti-war movement was nearly universal until Kenneth Bindas and Craig Houston popped the bubble in 1989 with their article on rock music and the protest myth in The Historian.

Since then, rock has often been criticized—mostly from the Left—as being insufficiently revolutionary. Woodstock, once a muddy-but-golden moment in which rock music reached its pinnacle, has more recently been described in less enthusiastic terms. In fact, rock was extremely revolutionary, only not here in the West. It played an unappreciated role in bringing down the Iron Curtain, or, at least, so say many of those inside the former Soviet bloc who clung to it as their lifeline.

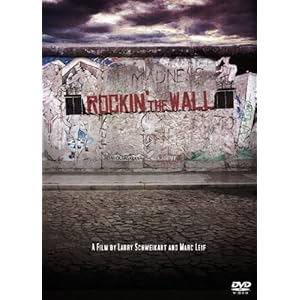

Two streams came together while I was in the process of researching a chapter for Seven Events that Made America America on rock music. First, having been a rock drummer for many years, opening for the legendary group Steppenwolf, as well as the James Gang and Savoy Brown, I briefly returned to my roots (or, in my case, my sticks) to investigate the power of rock. Then, through an almost accidental connection with Mark Stein, the incredible lead voice and keyboardist of the ‘60s band Vanilla Fudge, we began working on a history of the Golden Age of rock together. These opportunities opened up doors for interviews with dozens of classic (and even a few current) rockers: Billy Joel, Alice Cooper, Dave Mason (Traffic), Rudy Sarzo (Quiet Riot), Robby Krieger (The Doors), David Paich (Toto), and members of Deep Purple, Badfinger, Manfred Mann, the Yellowjackets, Rare Earth, Sugarloaf, and, of course, Vanilla Fudge. Our discussions soon led us to the foundational core of rock, freedom, and from there, to the part rock music has played in expressing that freedom to the people of Eastern Europe. From there, director Marc Leif took an interest in the project, and this drummer-turned-historian had to become a producer as well, starting a company and raising nearly a half-million dollars to produce an 83-minute documentary, “Rockin’ the Wall.”

Central to our argument in the film was the hypothesis that rock music was about more than lyrics. While it was true, as one “witness” from the Ukraine told us, that “all the boys learned their English from rock music,” we heard repeatedly that the music itself was inherently appealing. Why? In the 1950s, when the State Department sent jazz bands on tours of the Iron Curtain, it had the same appeal. Why? We concluded that the very nature of jazz, country, and above all, rock, was the key element—that rock music, especially, structurally represented America. It was a music like no other: rock bands began a song together, ended together, but evolved into a form where you always had the solo, that essential ingredient of freedom and self-expression. Everyone from David Paich to Vince Martell talked about the solo; “kid” bands from Ohio to Los Angeles always included the solo; and even the funk-rock band Mother’s Finest (one of the stars in the film), who played in East Berlin just two weeks before the Wall came down, emphasized the solo. It seems fitting that the end of the “Golden Age” of rock, circa 1970, came with the dominance of bands such as Cream, whose members all played simultaneous solos in the solo section!

To be sure, jazz is often one big solo—but then again, that is part of the reason it has never achieved the popularity of rock, even with the Europeans. Rock demanded a communal, group effort (we might call it “society”) but never ignored the needs of the individual to be free. If there was a single word that leaped out from “Rockin’ the Wall,” whether from musicians or the “witnesses,” it was freedom. And behind the Iron Curtain, musicians did anything and everything to be free. The Soviet Union so feared rock that it attempted to subsidize bands for towing the Party line, literally creating a “Ministry of Rock.” (Cue Jack Black: “A Ministry of Rock. Are you *#$%Q@ me???”) Some bands played the game, most went underground, copying the Americans and Brits until finally, in 1986, the USSR let four groups tour the U.S. under the “Red Wave” tour. (The music left a lot to be desired, but you could sure hear the American influence.) Leslie Mandoki, a student activist in Hungary who was also a drummer in a popular group, noted that despite a clampdown on information, all it took was putting up a few hundred flyers on the major college campuses and he’d draw 5,000 people to an illegal concert. The trick was, he noted in the film, to write a “rat tail.” The rat tail was a song that ostensibly was about Ronald Reagan or the United States or capitalism—and would therefore clear censors—but which was obvious to all the kids to be a criticism of the Soviet system.

Another witness recalled that Bibles in her country were banned and churches closed, but the authorities allowed the rock musical “Jesus Christ Superstar” to tour. She noted she “came to Jesus” and was baptized through, well, the power of rock and roll.

Perhaps the most illustrative rock moment, as described in the film, came when Mother’s Finest took their tour bus into the Eastern zone. An officer with a double-buttoned jacket boarded the bus. “Who is ze leader?” he asked in a stern voice. Lead singer Glenn Murdock raised his hand. Looking back and forth from Murdock’s face to Murdock’s passport picture, he instructed the singer, “To ze back of za bus!” Murdock went back and closed the curtain, wondering if he would be arrested. Looking in all directions, the officer unbuttoned his jacket . . . and pulled out a Mother’s Finest album. “You vill sign?” he asked. “I bring another next time.”

Rock music was blasted to through the Iron Curtain through government-subsidized Voice of America and Radio Free Europe, and we interviewed the legal counsel for VOA who described the debates inside the Reagan administration about the appropriateness of sending “degenerate” rock music eastward. But even the advisory boards came to understand that it was the structure of rock, as much as the lyrics, that counted. Yet that raised another interesting argument about the freedom inherent in rock music: until it reached VOA, rock was entirely unsubsidized and unregulated. It was a music that grew up from the people, not government. Fortunately, in America there was no Ministry of Rock to turn gems of rock genius into manure of mediocrity. No National Endowment for the Arts fueled the Golden Age of possibly the greatest music form of the twentieth century—and for that, based on our interviews, the people of the former Soviet Bloc seem extremely grateful.