David Silbey: The “traditional forms of history are dying” meme

The “traditional forms of history are dying” meme is strong within conservative precincts, and, oddly, the New York Times. “Traditional” in this case usually means one of a choice of political, diplomatic, economic or military history. The regular story is that these important kinds of history are being excluded from academia by (unstated but usually implied) less important forms of history that involve politically correct topics like race and gender. The articles are written from the viewpoint of the traditional forms of history, and those quoted represent those forms. Input from those historians practicing the PC forms are largely ignored.

A canonical example of this came a few years ago, in the National Review. John Miller wrote “Sounding Taps: Why Military History is being retired,” which took as its starting point the inability of the University of Wisconsin to fill the Ambrose-Hesseltine Chair in Military History. Miller’s article is typical of the breed. It nodded to the “official reason” why the Chair hasn’t been filled, but then pivoted to the “real” explanation:

The ostensible reason for the delay is that the university wants to raise even more money, so that it can attract a top-notch senior scholar. There may be another factor as well: Wisconsin doesn’t actually want a military historian on its faculty. It hasn’t had one since 1992, when Edward M. Coffman retired. “His survey course on U.S. military history used to overflow with students,” says Richard Zeitlin, one of Coffman’s former graduate teaching assistants. “It was one of the most popular courses on campus.” Since Coffman left, however, it has been taught only a couple of times, and never by a member of the permanent faculty.

And even the military history that some are doing was not acceptable to Miller because their military history took as its main focus social and cultural concerns. Thus had military history been “infiltrated” by social history to the cost of the real kind of military history, operational military history (this ignored–as Mark Grimsley pointed out) that Mac Coffman, Wisconsin’s emeritus military historian, was actually a social historian of the American Army. Never mind the facts, we have a narrative to write.

But this post is not mainly about Miller’s article. That came out a while ago, and others have done a good job of shredding it: Grimsley’s post mentioned above, and a number of others by him, which are gathered here. There was also a useful discussion on H-War.

No, this post is about the way in which the narrative overcomes the reality. This is nowhere in evidence more than in the most recent article of the genre, Patricia Cohen’s piece in the New York Times. The article starts off with the standard lead-in:

To the pessimists evidence that the field of diplomatic history is on the decline is everywhere. Job openings on the nation’s college campuses are scarce, while bread-and-butter courses like the Origins of War and American Foreign Policy are dropping from history department postings. And now, in what seems an almost gratuitous insult, Diplomatic History, the sole journal devoted to the subject, has proposed changing its title.

For many in the field this latest suggestion is emblematic of a broader problem: the shrinking importance not only of diplomatic history but also of traditional specialties like economic, military and constitutional history

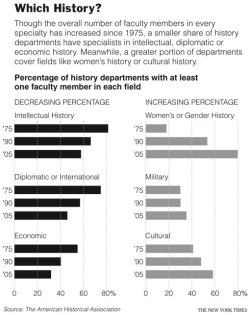

It goes on in this vein, quoting senior diplomatic historians and a lone graduate student, mostly commiserating the state of the field. All in all, it’s a pretty standard example of the type.Others have done more extended jobs critiquing the article for its lack of any voices on the other side of the debate, or looking at the assumption that fields can’t evolve and change their approaches. What I want to look at, instead, is the accompanying chart:

The data is courtesy of the American Historical Association, but the thing that struck me was that the number of military history positions has been flat (1975-1990) or growing (1990-2005). This is in contrast to diplomatic and economic history positions, which are declining, but similar to cultural history and gender history positions, which are increasing.

That surely does not fit the accepted wisdom of the declining state of military history within the academy, of the reluctance of politically-correct departments to hire “warmongers,” or of a generation of military historians retiring and not being replaced. (Nor, should I note, does the fact that the University of Wisconsin did actually hire a military historian for the Ambrose-Hesseltine Chair, something that John J. Miller does not seem to have acknowledged anywhere). So perhaps the view of what’s going on should be a little more nuanced? Maybe there’s room for an investigation of what’s actually going on? If military history is a traditional field being evicted by trendy historians of society, cultural, race, gender, etc., why are the number of positions increasing recently? Surely, there’s a discussion to be had?

Actually, no. The bizarre thing about the growth in military history revealed by the article is that nobody noticed, not even the author of the article. Close to the end of the article, Cohen put in an anecdote about the problems of military history in the academy:

Simply giving everyone a place at the table is just not affordable in an era of shrinking resources. “I’d love to let a hundred flowers bloom,” said Alonzo L. Hamby, a history professor at Ohio University in Athens, but “it’s hard for all but the largest departments or the richest.” In his own department of about 30 faculty members, a military historian recently retired, triggering a vigorous debate over how to advertise for a replacement. (A handful of faculty members had the view that “military history is evil,” Mr. Hamby said.) The department finally agreed to post a listing for a specialist in “U.S. and the world,” he said, “the sort of mushy description that could allow for a lot of possibilities.”

The conclusion pushed by the anecdote is, of course, that military history is on the way out, a conclusion belied by the chart in the article itself, a contradiction never addressed.

The strangeness continued. Reactions to the article all accepted uncritically the words of the article, and paid no attention to the actual numbers presented. A letter to the editor simply repeated the trinity of “traditional” history courses:

You report that the number of college courses in diplomatic, military, legal and economic history is shrinking, while the number of courses in social and cultural history is increasing

Stan Katz at the Chronicle went even further and erroneously reported that the numbers supported Cohen’s assertions:

She cites figures provided by the ever-reliable Rob Townsend of the American Historical Association showing that, indeed, there has been a substantial decrease in the number of diplomatic historians over the past 30 years — and that the same is true of specialists in military and economic history.

Of all the notes or reactions to this article, only Ralph Luker at Cliopatria picked up on the increase in military history. The received story is evidently so powerful and so assumed that even those who disagreed with it (like Timothy Burke and Claire Potter) still brought its premises, even when presented with clearly contradictory evidence. The tension between “traditional” and “cutting-edge” forms of scholarship is a powerful narrative device. Add to that the perceived tension between “right-wing” military history and “politically-correct” social and gender history, and it seems like military history should be part of the pack of traditional specialties, specialties being marginalized within left-wing history departments. That the evidence is much more ambiguous than that must then be ignored.

Never mind the facts, we have a narrative to write.