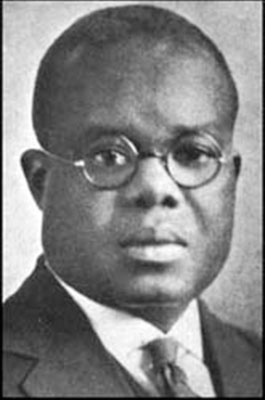

Is This the Black Activist Everybody Forgot?

Hubert H. Harrison (1883-1927) is the Black intellectual and activist you never heard of – but should. He was extremely important in his day and his significant contributions and influence are attracting increased study and discussion today.

His unrivalled soapbox oratory provides a good lead-in to his importance. In a fascinating precursor to the Occupy Wall Street movement the September 14, 1912, New York Times described how “Hubert Harrison, an eloquent and forceful negro speaker, shattered all records for distance in an address on Socialism in front of the Stock Exchange building yesterday.” His “voice carried to the furthermost limits of the crowd,” he “was still going strong, at the beginning of the third hour,” and he continued on until “the big gong in the Exchange announced the closing.” That same year the popular and tireless Harrison also addressed 50,000 people at Union Square on May 1 and spoke as many as 23 times a week for the Socialists during the election campaign. The New York News claimed that during 1912 Harrison was "the most trusted and valued speaker of the Socialist Party in the city" and "demands were sent to the Party for his services as speaker and debater all over the United States."

The following year Henry Miller, a young activist and future novelist, saw Harrison speak at Madison Square and never forgot it. Forty years later he vividly described (in The Rosy Crucifixion, Book Two: Plexus) his “quondam idol” and how he "learned standing at the foot of his soapbox":

There was no one in those days . . . who could hold a candle to Hubert Harrison. With a few well-directed words he had the ability to demolish any opponent. He did it neatly and smoothly too, "with kid gloves," so to speak. I described the wonderful way he smiled, his easy assurance, the great sculptured head which he carried on his shoulders like a lion. I wondered aloud if he had not come from royal blood, if he had not been the descendant of some great African monarch. Yes, he was a man who electrified one by his mere presence. Besides him the other speakers, the white ones, looked like pygmies, not only physically but culturally, spiritually. Some of them, like the ones who were paid to foment trouble, carried on like epileptics, always wrapped in the Stars and Stripes, to be sure. Hubert Harrison, on the other hand, no matter what the provocation, always retained his self-possession, his dignity. He had a way of placing the back of his hand on his hip, his trunk tilted, his ears cocked to catch every last word the questioner, or the heckler put to him. Well he knew how to bide his time! When the tumult had subsided there would come that broad smile of his, a broad, good-natured grin, and he would answer his man -- always fair and square, always full on, like a broadside. Soon everyone would be laughing, everyone but the poor imbecile who had dared to put the question . . ..

Over the next two years Harrison broke from the Socialist Party because he thought it put the “[white] Race First, and class after.” He continued speaking on a wide range of topics, indoors and outdoors, however. His wide-ranging list of talk topics now included religion, science, literature, history, politics, birth control, evolution, freethought, the war in Europe, and anarchism and he was involved in important free speech struggles (and arrested for speaking) in New York City and upstate NY.

In 1915, James Weldon Johnson, former diplomat, author of “Lift Every Voice and Sing” (“The Negro National Anthem”), and the future first Black Executive Secretary of the NAACP wrote an editorial in the New York Age (New York’s largest Black weekly) explaining that Harrison on a soapbox could provide “a university extension carried to the farthest point.” He could “attract people who wouldn’t go to a lecture, but would listen to a lecture if it was brought to them.” Johnson urged that “An Open Air Lecture Course” be arranged in Harlem with Harrison as the speaker.

Harrison soon turned to concentrated work in Harlem’s Black community where he pioneered the tradition of militant soapbox oratory, which would subsequently include such important figures as A. Philip Randolph, Richard B. Moore, Marcus Garvey, and, much later, Malcolm X. As a soapbox orator Harrison was brilliant and unrivalled. Factual and interactive, he exhibited wonderful mastery of language, humor and irony and, when appropriate, he employed a biting sarcasm. William Pickens, an oratory prize winner at Yale and future college dean and NAACP leader, saw Harrison speak in the 1920s and described him as “a plain black man who can speak more easily, effectively, and interestingly on a greater variety of subjects than any other man I have ever met in the great universities.”

The impact of Harrison’s soapbox oratory was profound. As journalist Oscar Benson explained in the New York News:

. . . he instituted a new school of social thought, packed a new forum, dignified the soap-box orator; blocked Lenox and Seventh Avenue traffic; sent humble men to libraries and book stores; sent them about to day and night schools; taught Negroes to think for themselves; taught them that in spite of all the handicaps of slavery and propaganda of anthropologists and sociologists, who said that the Negro was an imitator, that no one knew what the Negro could do until he tried. . . .

His doctrine of self-reliance, of self-respect, of confidence in yourself and in your race; his researching; bringing upon the public highway, . . . his reflection upon modern topics and his comments upon the modern action of world leaders, made his services of latent value in the community in which he lived; if not unparalleled within the history of the Negro. No man ever held the attention of such large crowds upon the public highway in Harlem, nor with their addresses made such an active impression . . .

Hubert H. Harrison was much more that a brilliant soapbox orator, however. He was also a brilliant writer, educator, critic, and political activist. Historian Joel A. Rogers, in World’s Great Men of Color described the self-educated Harrison as “the foremost Afro-American intellect of his time.” This extraordinary praise came amid chapters on Booker T. Washington, W. E. B. Du Bois, William Monroe Trotter, and Garvey. Rogers adds that “No one worked more seriously and indefatigably to enlighten” others and “none of the Afro-American leaders of his time had a saner and more effective program.” Labor and civil rights leader Randolph described Harrison as “the father of Harlem Radicalism.” Harrison’s friend and pallbearer, Arthur Schomburg, fully aware of his popularity, presciently eulogized to the thousands attending Harrison’s Harlem funeral that he was also “ahead of his time.”

Born in St. Croix, Danish West Indies, on April 27, 1883, to a Bajan mother and a Crucian father, Harrison arrived in New York as a seventeen-year-old orphan in 1900. He made his mark in the United States by struggling against class and racial oppression, by helping to create a remarkably rich and vibrant intellectual life among African Americans and by working for the enlightened development of the lives of those he affectionately referred to as “the common people.” He consistently emphasized the need for working class people to develop class-consciousness; for “Negroes” to develop race consciousness, self-reliance, and self-respect; and for all those he reached to challenge white supremacy and develop an internationalist spirit and modern, scientific, critical, and independent thought as a means toward liberation.

A self-described “radical internationalist,” Harrison was extremely well-versed in history and events in Africa, the Caribbean, Asia, the Mideast, the Americas, and Europe and he wrote voluminously and lectured indoors and out on these topics. More than any other political leader of his era, he combined class-consciousness and anti-white supremacist race consciousness in a coherent political radicalism. He opposed capitalism and imperialism and maintained that white supremacy was central to capitalist rule in the United States. He emphasized that “politically, the Negro is the touchstone of the modern democratic idea”; that “as long as the Color Line exists, all the perfumed protestations of Democracy on the part of the white race” were “downright lying” and “the cant of ‘Democracy’” was “intended as dust in the eyes of white voters”; that true democracy and equality for “Negroes” implied “a revolution . . . startling even to think of,” and that “capitalist imperialism which mercilessly exploits the darker races for its own financial purposes is the enemy which we must combine to fight.”

Working from this theoretical framework, he was active with a wide variety of movements and organizations and played signal roles in the development of what were, up to that time, the largest class radical movement (socialism) and the largest race radical movement (the “New Negro”/Garvey movement) in U.S. history. His ideas on the centrality of the struggle against white supremacy anticipated the profound transformative power of the Civil Rights/Black Liberation struggles of the 1960s and his thoughts on “democracy in America” offer penetrating insights on the limitations and potential of America in the twenty-first century.

Harrison served as the foremost Black organizer, agitator, and theoretician in the Socialist Party of New York during its 1912 heyday; he founded the first organization (the Liberty League) and the first newspaper (The Voice) of the militant, World War I-era “New Negro” movement; edited The New Negro: A Monthly Magazine of a Different Sort (“intended as an organ of the international consciousness of the darker races -- especially of the Negro race”) in 1919; wrote When Africa Awakes: The “Inside Story” of the Stirrings and Strivings of the New Negro in the Western World'" in 1920; and he served as the editor of the Negro World and principal radical influence on the Garvey movement during its radical high point in 1920.

His views on race and class profoundly influenced a generation of “New Negro” militants including the class radical Randolph and the race radical Garvey. Considered more race conscious than Randolph and more class conscious than Garvey, Harrison is the key link in the ideological unity of the two great trends of the Black Liberation Movement -- the labor and civil rights trend associated with Martin Luther King, Jr., and the race and nationalist trend associated with Malcolm X. (Randolph and Garvey were, respectively, the direct links to King marching on Washington, with Randolph at his side, and to Malcolm (whose father was a Garveyite preacher and whose mother wrote for the Negro World), speaking militantly and proudly on street corners in Harlem.

Harrison was not only a political radical, however. Rogers described him as an “Intellectual Giant and Free-Lance Educator,” whose contributions were wide-ranging, innovative, and influential. He was an immensely skilled lecturer (for the New York City Board of Education) who spoke and/or read six languages; a highly praised journalist, critic, and book reviewer (who reportedly started "the first regular book-review section known to Negro newspaperdom"); a pioneer Black activist in the freethought and birth control movements; and a bibliophile and library builder and popularizer who was an officer of the committee that helped develop the 135th Street Public Library into what has become known as the internationally famous Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture.

Hubert Harrison was truly extraordinary and people are encouraged to learn about and discuss his life and work and to Keep Alive the Struggles and Memory of this Giant of Black History.