The Great Book Review War: Kinsley vs. Greenwald vs. Sullivan (and of course Snowden)

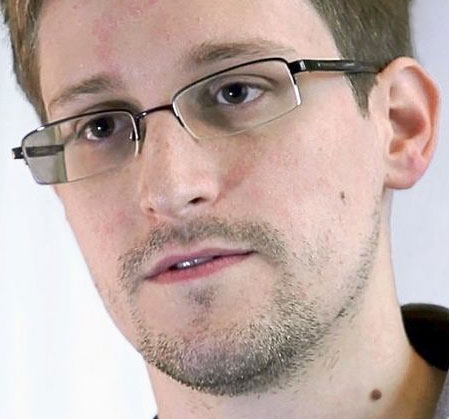

A battle of accusations and counter-accusations began with a New York Times Sunday book review posted online before it ever appeared in print. Glenn Greenwald's new book No Place to Hide was assigned for review to Michael Kinsley, a longtime editor and journalist who is now with Vanity Fair. The book deals with NSA insider Edward Snowden’s now-famous exposure of top secret documents, which Greenwald writes, add up to “secret state surveillance and abuse of power.”

It was in a Hong Kong hotel room that, as first told by Luke Harding of the Guardian in his 2014 book The Snowden Files, Snowden handed Greenwald, the documentary filmmaker Laura Poitras and the veteran Guardian reporter Ewen MacAskill the ultra-secret Presidential Policy Directive 20, dated October 2012, in which Snowden claimed the President had secretly ordered intelligence agencies to create a listing of possible foreign targets for cyber attacks and therefore, as Harding put it, allowing the “tapping [of] fiber-optic cables, intercepting telephony landing points and bugging on a global scale.” The trio, writes Greenwald, “felt they were involved in a joint endeavor of high public importance, with a large degree of risk.” Even Kinsley, in a rare compliment, admits that the meetings in Hong Kong were “full of journalistic derring-do…a great yarn.”

I don’t know if Kinsley and Greenwald have ever met, but it’s obvious from the review’s tone that Kinsley hasn’t much regard for him. Greenwald strikes Kinsley as“unpleasant” and “Maybe he’s charming and generous in real life. But in No Place to Hide, Greenwald, “the go-between” for Snowden and the newspapers with whom Greenwald dealt, “seems like a self-righteous sourpuss, convinced that every issue is ‘straightforward’ and if you don’t agree with him you’re part of something he calls the ‘authorities’ who control everything for their own nefarious but never explained purposes.”

From there the review is all downhill, and the reactions to it are equally negative. Writing about another subject, the Times’s Mark Leibovich said “the personal has never been more political, and vice versa.” So it is for Kinsley. Continuing in a provocative way, he writes that Greenwald -- an experienced litigator and journalist-- “in his mind,” (how can Kinsley be certain?) resembles “a ruthless revolutionary—Robespierre or Trotsky.”

Kinsley’s review is also replete with snap judgments. “Reformers tend to be difficult people,” he writes. Julian Assange is a ‘narcissist ’ and Snowden “appears to yearn for martyrdom”— an assertion that ignores that Snowden insists he’s a patriot and that after 9/11 he served in the army before receiving a medical discharge. As for Greenwald, he is someone who seems to believe “The ancient regime is corrupt through and through, and he is the man who will topple it.”

Still, while Kinsley’s review often sounds like a writer pressing to meet his word requirement, it’s all fair play given the extraordinary significance of Snowden’s disclosures and Greenwald’s role in publicizing them. But no sooner had he finished attacking Greenwald, than Kinsley stepped into a literary and political minefield. “The question is who decides,” specifically, which government documents and secrets may be published by the press, and he answers: “That decision must ultimately be made by the government” (my italics).

His categorical conclusion was simply too much for the paper’s Public Editor Margaret Sullivan. Stepping out of her role (or fulfilling it?) as a critic of the paper’s contents, she criticized the selection of Kinsley as the reviewer suggesting that he was opposed to Snowden’s release of secret documents and those involved. She chose to quote one of her outraged readers that the choice of Kinsley meant that “the result is as predictable in its own way as having Jeremy Scahill [a critic of U.S. foreign policy] or James Clapper [the Director of National Intelligence] review it. Wouldn’t it have been better to have chosen someone with a more balanced take on both Greenwald and the arguments he makes to evaluate the book?”

And then she struck at Kinsley’s “who decides” argument. “Mr. Kinsley’s central argument ignores important tenets of American governance…. the Founders explicitly intended the press to be a crucial check where “the press [is] a crucial check on the power of the federal government…Picture Daniel Ellsberg and perhaps Times reporter Neil Sheehan in jail and think of all that Americans would still be in the dark about—from the C.I.A.’s black sites to the abuses of the Vietnam War to the conditions at the Walter Reed Army Medical Center to the widespread spying on ordinary Americans”

When Pamela Paul, the book review’s editor, replied that it wasn’t her role to edit a reviewer’s judgment and moreover, a book review wasn’t an editorial but simply one person’s opinion, Sullivan responded that while Kinsley was free to air his opinions “there’s a lot about this piece that is unworthy of the Book Review’s high standard. She then took direct aim: “A Times review ought to be a fair, accurate and well-argued consideration of the merits of a book. Mr. Kinsley’s piece didn't meet that bar.”

No way was the squabble going to end there. “Who will protect the public from the public editor?” snapped Kinsley, obviously stung. “The government sometimes has legitimate reasons for needing secrecy but “will usually be overprotective” and any decisions “should openly tilt in favor of publication with minimal delay.” And more: “Do I want to have sent Dan Ellsberg and Neil Sheehan to jail for leaking?... Like most people except Glenn Greenwald, I think the issue is complicated and I have other things to do. But the answer to the Ellsberg-and-Sheehan questions is, no.”

Greenwald also came back at Kinsley. Describing Kinsley as “the consummate establishment 'liberal’ insider,' ” he decried the demonization by the government and its “jingoistic media courtiers” of anyone who offers “any fundamental critiques of American political culture.” His response to Kinsley added his ally Daniel Ellsberg’s tweet, “I wonder how many years Kinsley now thinks I should have spent in prison for revealing the Pentagon Papers?”

Writing in the neoconservative Commentary magazine (whose reviewers and writers have rarely if ever deviated from the magazine’s rigid party line) and referring to Sullivan’s concerns, James Kirchick reminded us that last August the Times magazine published a sympathetic profile of Laura Poitras, a close associate of Greenwald and Snowden. Kirchick wrote, mockingly, not without merit but reeking with Gotcha!, that the assignment of Peter Maass to write the piece was followed by his later being “rewarded for his obsequiousness with a job as senior editor at none other than First Look Media,” Greenwald’s new home.

Immediately, many media people began choosing sides. Big names and lesser known names, pundits, reporters and mediaphiles chimed in. The New Republic’s Adam Kirsch tried to mediate the fracas but no-one was ready for his sensible approach because the “spat” as he described it, was much more than a typical 24/7 backyard brawl. The issues separating the sides couldn’t be wished away.

In my view, Pamela Paul, the Times’ s book review editor, was in her rights to have selected a reviewer of her choice, as a review is an opinion not an editorial. As the paper’s Ombudswoman, Margaret Sullivan was free to comment on anything in the paper and she may be its most perceptive in-house critic ever, but she was out of bounds in going after the selection of Kinsley as the reviewer.

The real issue and which was properly challenged by Sullivan and others was that Kinsley came too close to suggesting that, however complex the issue, it is Washington who decides , not the press. Some of Kinsley’s proponents seem to rely on the straw man argument: What, if someone published the date of the D-Day landing or some similar momentous event and thereby caused the invasion to be blunted and tens of thousands of soldiers killed? This has never occurred and likely would never occur so great would be the outcry. In the Snowden case, we’re talking instead about the necessary exposure of massive spying and cover-ups. Anyone still interested in the history of our many questionable and unnecessary wars in 1898, 1917, 1950, 1965 and 2003, each grounded in lies, the truth hidden from the public.

Of course Kinsley had every right to say whatever he wanted. He even admits that Snowden’s leaks were “a legitimate scoop,” but should the famous young exile ever return home he faces a certain Chelsea Manning –like prison sentence, just as the Obama administration has chosen to charge eight alleged leakers with violating the infamous 1917 Espionage Act.

In the end, without Snowden and Greenwald and others--as even Kinsley acknowledges --- who would have known about Prism and massive domestic and international spying? Who will know about the other NSA “secrets” Snowden or other insiders may release in the future? Conscience and principles matter and sometimes they demand great personal risks, which Kinsley somehow failed to mention in his review. It’s wise to recall Judge Murray Gurfein’s ruling in the Pentagon Papers case: “A cantankerous press, an obstinate press, a ubiquitous press must be suffered by those in authority in order to preserve the ever greater values of freedom of expression and the right of the people to know.”

Meanwhile, the disagreements will continue. Barton Gellman of the Washington Post will soon be out with his book on the Snowden revelations while others will certainly follow. I wonder who the Times will assign as reviewers?