Channeling George Washington: Are We At War?

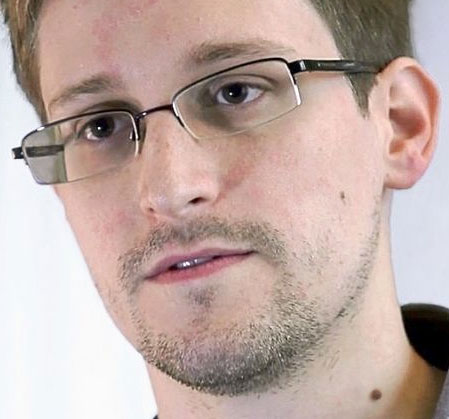

“It’s about time someone asks – and asks and asks – the crucial question about Edward Snowden – are we at war or aren’t we?”

“Why do you ask it, Mr. President?”

“Because my question connects Snowden’s supposed outrage at NASA’s secret surveillance program in a very strong way with an experience I had in 1798 with the Alien and Sedition Acts – and from there to what other presidents have had to do – or thought they had to do – to win a war.”

“Let’s start with the Alien and Sedition Acts. How do they relate to Edward Snowden?”

“Thousands of people have often refused to admit that our government has a right to defend the lives and property of our citizens in wartime by seemingly extreme steps that our leaders judge to be necessary. The Snowden case is not a new phenomenon. The dispute is often rooted in whether or not we are at war. When the government passed the Alien and Sedition Acts in 1798, we were fighting an undeclared war with Revolutionary France. Hundreds of our ships and thousands of our seamen were being assaulted on the high seas. There were fears of a French army invading the country. The President of the United States, John Adams, asked me to emerge from retirement and take command of an enlarged American army.”

“Why did these people think the laws were necessary?”

“There were thirty thousand French refugees from their revolution in America. We had no way of knowing how many of them might be secret agents, working for their government. During my presidency, we’d experienced the French attitude, that they were leading a world-wide revolution which gave them the authority to take control of governments whenever and wherever they pleased.. They sent us an ambassador who talked of appealing to the American people over the head of “Old Man Washington.” The Alien Act gave the president the power to expel any alien who threatened the nation’s safety and independence. Meanwhile, newspapers were spreading vicious lies about government officials. In my last months as president, they reprinted a series of letters forged by the British during the War for Independence, portraying me as the clandestine lover of a woman in New York. We knew that the French used similar techniques in Europe to destroy respect for governments, making them easier to conquer. The Sedition Act specified that if a newspaper or a politician who vilified a government official could not prove his facts in a court of law, he was liable to a jail sentence and a heavy fine.”

“Why did some people oppose these laws?”

Thomas Jefferson and his followers dismissed our losses at sea from French men of war as something we’d brought on by being too friendly with Britain. They considered both acts violations of the bill of rights. Before he stopped agitating, Jefferson was calling for “scission” -- his word for secession – rather than tolerate these laws. It was a veritable model of how far people like Jefferson were willing to go in the name of ideological purity – and their own political advantage.”

Did

anyone support the contention that the Alien and Sedition Acts were

necessary --- and legitimate?”

“The president of the United States, his cabinet, and a majority of Congress thought so. They had written the bills, and the president signed them. Congressman John Marshall, the future Chief justice of the Supreme Court, defended their constitutionality. He noted that they were temporary measures that would expire in two years, when everyone hoped the crisis – the undeclared war -- would be over.”

“The Jeffersonians won the argument over the acts, didn’t they?”

“That’s unfortunately correct. A year after they were passed, British victories over the French fleet eliminated the threat of French invasion. But John Adams allowed his political party -- the Federalists -- to continue to pursue Sedition Act prosecutions, helping to convince a lot of people that they were violating the Bill of Rights. By that time I was in Elysium and could only watch helplessly as this folly was perpetrated, handing the presidency to Tom Jefferson. As a result, generations of historians have mocked and condemned the acts, ignoring what was happening when they were passed. Eventually, other presidents would demonstrate in their wartime laws and decrees that the acts were not only legal, but worthy of study.”

“Could you describe some of these wartime presidents and their policies?”

“By far the most striking example is Abe Lincoln. During the Civil War, he suspended one of the most fundamental rights in our legal system, habeas corpus. At one point he arrested the entire Maryland legislature to make sure the state did not secede from the Union. Overall he jailed thousands of men who spoke out against the war. In Kentucky, he looked the other way while mobs, often led by Union troops, destroyed seventeen anti-war newspapers and intimidated Democrats into not voting in elections.”

“That’s quite an earful. Did anyone imitate Lincoln’s example?”

“In World War I, Congress passed a sedition act -- and President Wilson signed it -- that was so tough, a man could get five years in jail for publicly criticizing Woody’s conduct of the war. They jailed a Hollywood producer for making a movie that was too critical of our ally, Great Britain. They created 250,000 volunteer intelligence agents who reported on their neighbors suspected disloyalty, opened their mail, and tapped their phones.”

“Awesome.”

“In World War II, Franklin Roosevelt arrested and shipped to labor camps tens of thousands of Japanese Americans, who had not committed a crime, simply because they were suspected of disloyalty. He absolutely refused to say a word on behalf of Europe’s Jews as the Nazis slaughtered them because he feared that anti-Semitism in America would undermine the war effort. He ‘persuaded’ the press not to show a single picture of a dead American soldier or sailor or marine for over 18 months after we entered the war, because he feared support for the war would be damaged by the sight. No one criticized him for any of these policies.”

“You see the NASA surveillance policy in this tradition?”

“I see it as an inevitable and legitimate outgrowth of the kind of war we are fighting. The assault on the World Trade Center killed 2700 civilians – more than the number of soldiers and sailors killed at Pearl Harbor. Can anyone deny that we should be prepared to take extreme measures to avoid a repetition of these attacks? Only last year in Boston our enemies demonstrated they could strike again with bombs that killed and maimed dozens of people. If we are fighting a war, Edward Snowden’s attempt to cripple our effort to protect our citizens indicts him as a traitor. I don’t see how anyone can avoid this conclusion.”