Why Wars Always End Up Hurting the Most Vulnerable Americans

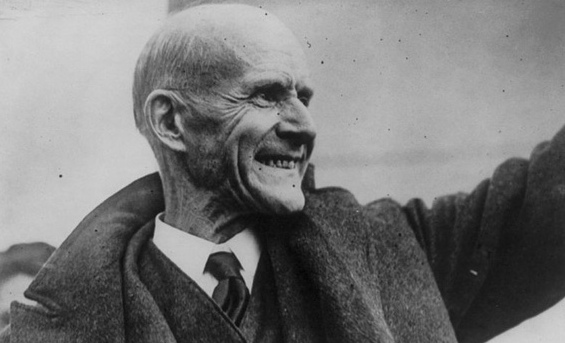

Eugene V. Debs leaves prison on Christmas Day 1921, after his 10-year sentence for opposing the draft was commuted. (Library of Congress)

...Most Americans have forgotten how repressive a period World War I was. “You can’t even collect your thoughts without getting arrested for unlawful assemblage,” quipped the writer Max Eastman. “They give you ninety days for quoting the Declaration of Independence, six months for quoting the Bible.” Walter Lippmann said Woodrow Wilson’s administration had “done more to endanger fundamental American liberties than any group of men for a hundred years."

Perennial Socialist presidential candidate Eugene Debs was sentenced to 10 years in jail for opposing the draft. Cincinnati outlawed the sale of pretzels; Iowa made publicly speaking German a crime.

Which makes it all the more remarkable that Lippmann had championed America’s entrance into the war on the grounds that it would further liberal ideals. While fighting for democracy in Europe, he declared, “we shall stand committed as never before to the realization of democracy in America ... we shall turn with fresh interest to our own tyrannies—to our Colorado mines, our autocratic steel industries, our sweatshops and our slums.” The progressive philosopher John Dewey thought the war would unleash a new spirit of public-mindedness in the United States and a “more conscious and extensive use of science for communal purposes.”

It’s easy to deride Lippmann and Dewey for their naïveté. But they’re in good company. Every time America launches a major war, intellectuals predict it will spawn a new culture of public spiritedness and political reform. In 1960, when John F. Kennedy promised to seize the initiative against communism in the developing world—Vietnam would become the test case—sympathetic intellectuals claimed the effort would energize America at home. “This is the challenge of the 1960s: the reorganization of American values,” wrote the historian and Kennedy confidante Arthur Schlesinger Jr. “If we are going to hold our own against communism in the world ... the production of consumer goods will have to be made subordinate to some larger national purpose.”

It was the same after 9/11. For conservative hawks, the “war on terror” offered the chance to replace the tawdry materialism of the 1990s with a devotion to higher things...