How Coffee Fueled the Civil War

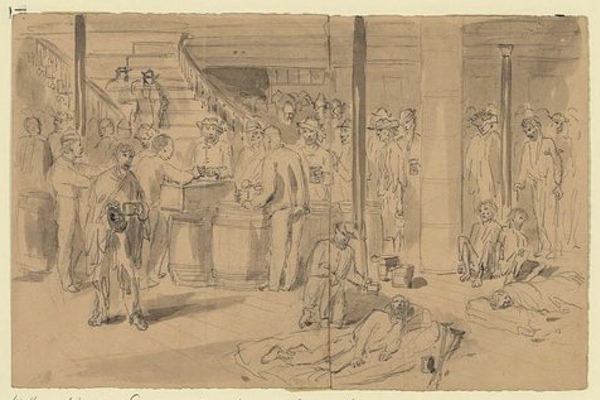

A sketch of exchanged Union prisoners receiving rations aboard the ship New YorkLibrary of Congress

It was the greatest coffee run in American history. The Ohio boys had been fighting since morning, trapped in the raging battle of Antietam, in September 1862. Suddenly, a 19-year-old William McKinley appeared, under heavy fire, hauling vats of hot coffee. The men held out tin cups, gulped the brew and started firing again. “It was like putting a new regiment in the fight,” their officer recalled. Three decades later, McKinley ran for president in part on this singular act of caffeinated heroism.

At the time, no one found McKinley’s act all that strange. For Union soldiers, and the lucky Confederates who could scrounge some, coffee fueled the war. Soldiers drank it before marches, after marches, on patrol, during combat. In their diaries, “coffee” appears more frequently than the words “rifle,” “cannon” or “bullet.” Ragged veterans and tired nurses agreed with one diarist: “Nobody can ‘soldier’ without coffee.”

Union troops made their coffee everywhere, and with everything: with water from canteens and puddles, brackish bays and Mississippi mud, liquid their horses would not drink. They cooked it over fires of plundered fence rails, or heated mugs in scalding steam-vents on naval gunboats. When times were good, coffee accompanied beefsteaks and oysters; when they were bad it washed down raw salt-pork and maggoty hardtack. Coffee was often the last comfort troops enjoyed before entering battle, and the first sign of safety for those who survived.

The Union Army encouraged this love, issuing soldiers roughly 36 pounds of coffee each year. Men ground the beans themselves (some carbines even had built-in grinders) and brewed it in little pots called muckets. They spent much of their downtime discussing the quality of that morning’s brew. Reading their diaries, one can sense the delight (and addiction) as troops gushed about a “delicious cup of black,” or fumed about “wishy-washy coffee.” Escaped slaves who joined Union Army camps could always find work as cooks if they were good at “settling” the coffee – getting the grounds to sink to the bottom of the unfiltered muckets.

For much of the war, the massive Union Army of the Potomac made up the second-largest population center in the Confederacy, and each morning this sprawling city became a coffee factory. First, as another diarist noted, “little campfires, rapidly increasing to hundreds in number, would shoot up along the hills and plains.” Then the encampment buzzed with the sound of thousands of grinders simultaneously crushing beans. Soon tens of thousands of muckets gurgled with fresh brew...