This Is What Happens When We Try to Reduce the Evil of Slavery to a Simple Formula

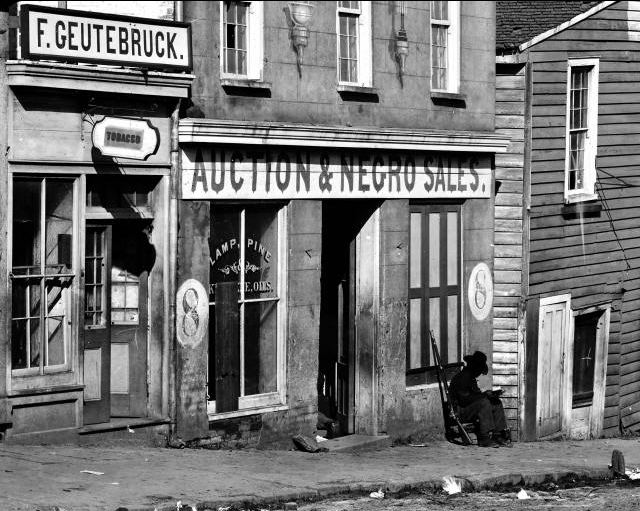

On September 4, 2014 The Economist reviewed Edward Baptist's new book, The Half Has Never Been Told: Slavery and the Making of American Capitalism. The review did not engage Baptist’s impressive archival research but instead flattened his multiyear study with the claim, "Almost all the blacks in his book are victims, almost all the whites villains." The review triggered a firestorm of reaction from tweets that claimed The Economist was racist to arguments that the American public still remains unwilling to accept the history of slavery. On September 6, The Economist removed the review and published an apology, claiming “Slavery was an evil system, in which the great majority of victims were blacks, and the great majority of whites involved in slavery were willing participants and beneficiaries of that evil. We regret having published this and apologise for having done so.”

Now that the smoke has cleared, it might be time to think a bit more about why such a review surfaced in the first place and the reaction to it. While the review is certainly problematic for its racist assertions, the responses to it are equally unsettling. Many readers and scholars who called for the removal of the review from The Economist's website have failed to see how the analytical frame of capitalism might have contributed to the reviewer's facile conclusions, and they have also overlooked the virulent ways in which the present continually informs the past, particularly when it comes to slavery.

Since its origin, writing the history of slavery has always been tethered to a contemporary social context. The reviewer's claims that, "Almost all the blacks in his book are victims, almost all the whites villains," seems less of an example of racism and more proof of historian Barbara Jeanne Fields' point that "the Civil War is still going on." Evidence of the war still being fought can be seen in everything from the films 12 Years a Slave and Spielberg's Lincoln to debates about reparations and history standards to even the symbolically charged nature of recent events in Ferguson, Missouri.

That The Economist removed the review only played into facile discussions about racism and slavery by demonstrating that silence and censure matter more than debate and dialogue. In a piece that he wrote for Politico Magazine, Baptist even seems a bit perturbed by The Economist's decision to not engage his book on its own terms. But when has the history of slavery ever been accurately told and, more to the point, how has calling slavery "capitalist" only played into these problematic conclusions? As for the public outrage in response to the review, how has the notion of capitalism made the history of slavery legible to broader audiences? Historians have documented the horrors of slavery for almost a century and have connected slavery to economics and power, but how has the discourse of slavery and the “making of American capitalism” make all of this seem brand new? Further, does the argument that slavery provided the foundation for modern capitalism impose a Whiggish history of the past?

The major problem with the review in The Economist is that it does not state that the subject of capitalism's relationship to slavery has been debated for decades among historians, and that Baptist is a newcomer to the conversation, not the inventor of it. Historian Seth Rockman notes "the question of whether the slaveholders were capitalists or not made for a frequent qualifying exam question" for graduate students.

By participating in this age-old debate, Baptist follows the contours of the historiography set over four decades ago and establishes an analytical framework that assigns logic to a system of slavery that does not follow clear patterns. Cultural historians, literary scholars and anthropologists have over the last few decades continually explained the limitations in writing the history of slavery and the problems of the archives which house these records. They detail the inability to capture accurate numbers, the large quantity of missing records, and the gaps within collections as well as the indecipherability to understand the nuances of slavery. Yet, call slavery capitalist and add a chart, and the gaps in the archive suddenly disappear, the numbers add up, and the illogic that gave way to pro-slavery discourse inches toward rationality.

Take the label of capitalism away, and slavery appears peculiar in the way that antebellum northerners viewed it in all its idiosyncratic and often immutable, uncharacteristic ways -- as Jennifer Morgan once brilliantly said "Much of the scholarly work on the history of slavery is, indeed, in search of a metaphor." Yet, call the system of slavery capitalistic, apply a complicated but nevertheless cogent framework to it, and its easy to see the urge by some readers to see slavery as a study of good verse evil. Revel, however, in its peculiarity, its almost legendary reticence to be defined, and one won't be able to easily denigrate its history to a morality play. The application of a capitalistic framework leaves out a whole lot of the history of slavery, and in fact works to the advantage of those who want us to believe in the invincibility of capital at the cost a whole host of other crucial factors, like agriculture and the environment, that played significant roles in the expansion of slavery. Soil, land, climate, rainfall and other environmental forces played more of a part in dictating cotton's future than the entrepreneurial desires of the most rapacious slaveholders or the demands of the international markets. As Lynn A. Nelson points out in his biography of a Virginia plantation, Pharsalia, planters often failed to follow and understand basic rules of agriculture. Yet, according to the logic of capitalism, the environment cooperated with their greedy desires. If capitalism becomes the omnipresent demigod dictating power relations, no wonder some readers conclude slaves are victims and slaveholders are villains. If one calculates the environment as an actor, as Walter Johnson skillfully did in River of Dark Dreams, then we can better see the exigencies of various other factors that shaped the making of the peculiar institution.

The argument that Baptist's book is a story of victims is not an invention of the reviewer but rather the result of Baptist's imaginative reconstruction that others have recently criticized. In his review in the Wall Street Journal, Fergus Bordewich notes that Baptist "resorts too often to novelistic devices that undermine the reader's patience and trust."

The brouhaha surrounding Bapitst's book, nevertheless, offers an opportunity to consider what is at stake in this allegedly new move to consider the history of capitalism in the context of slavery. On one level, calling slavery a capitalist system can obfuscate and lead to erroneous conclusions, as the reviewer in The Economist did. On another level, it overlooks recent historiographical. developments and it plays into the framework of old debates. One of the most transformative interventions into the history of slavery's development has been its connections to Native Americans in the South, which introduced new understandings of the very definitions of slavery and freedom, community and geography, and especially capital. Yet following capital's growth from the ways in which antebellum bankers, financiers, and slaveholders documented its movement from the Upper South to the Mississippi Valley marginalizes these developments, privileges their logic, and reinforces the way antebellum capitalists wanted the economic narrative to be seen and to be understood. Consider Native Americans, not just as observers who referred to the land as "dark and bloody ground," but rather as actors who actually shifted the terms of the debate and made land accessible for cotton cultivation, similar to the way Pekka Hämäläinen documents how the Comanche Empire set the parameters for the American acquisition of territory during the Mexican American War; and a completely different analysis of the flow of capital, the geography of the South, and the meaning of bondage may surface.

This new scholarship on capitalism also brokers power relations into simply defined categories that do not actually adhere to the social dimensions of either the history of slavery or the South. Not just Baptist, but many leading historians have cast white slaveholders and enslaved people as the only actors of the antebellum period, and have excluded yeomen and poor whites, Native Americans, women, the small but increasing number of Northern migrants and European immigrants. In casting white slaveholders as the leading protagonists in this narrative, they define them as homogenous despite the fact that these men (and few women) continued to draw sharp distinctions among them even to the days leading up to the Civil War when they fought on the same side of the Mason-Dixon line. Yet, in the histories of capitalism all of these men become grouped together as homogenous because of their abilities to earn profit, despite the fact their profits varied, or, at times, showed little increase based on the season and the climate.

These new studies of capitalism also homogenize the enslaved populations as well. Historians Ira Berlin and Philip Morgan painstakingly revealed the differences in slavery based on time and place, but these interpretations seem to fade from view when capitalism moves to the center.

Additionally, the lack of attention to gender in these new studies of capitalism has also contributed to the argument of white versus black. If nothing else, gender revealed the struggle and discontent within social groups that have heretofore been labeled as homogenous. Gender reveals how notions of masculinity pushed men to compete with each other, or, as Stephanie McCurry cogently demonstrated, to obtain slaves in order to prove one's status and power. Yet, little of this seems to be part of this new historiography on capitalism, as scholars are taking their cue from previous debates.

What about the ways in which gender historians, like Thavolia Glymph, have argued that enslaved women's emotional and physical labor is often invisible and that it can't be measured by the same scales that measured pounds of cotton as the only source of capital? Providing food, birthing the babies, sacrificing food for children, the kind of work that makes the labor force tractable under capitalism, how did this form of enslaved labor, which often does not get economically quantified in planters ledgers, shape the development of capitalism?

While some of the new histories of capitalism acknowledge the existence of poor whites and yeomen, they don’t appear as central actors but rather as pawns who gets lost in the broader saga of capitalism. This is to say nothing, of course, of the growing population of free black people in places like South Carolina and Louisiana—who also appear absent from these studies. Seth Rockman, however, in his compelling study of Baltimore, Scraping By, offers an instructive model on how to write the history of capitalism by equaling treat the various social groups that populated Baltimore—women, free blacks, the enslaved and immigrants. Due to Rockman’s diverse subjects, a reviewer would not be able to reduce his book to simply a narrative of black verse white.

It seems reactionary, therefore, to simply indict The Economist as racist and shutdown the discussion without considering the context in which the review surfaced or even the limitations of using capitalism as a framework to examine slavery.

Instead of silencing debate, scholars should have demanded The Economist to open a conversation about the history of slavery, the notion of victimhood, and the subversive, often hidden, ways that racism unfolds. If academics want to reach non-academic audiences, especially by publishing with trade presses, they must be prepared that their readers might make odd, uniformed, and racist comments. Instead of calling it racist and telling The Economist to banish the review like it's an Ebola outbreak, scholars ought to consider it as "a teaching moment." Explain how slavery predated racism, not the other way around. Use the comments' sections to offer suggestions to other readings or the long history of why such claims are problematic rather than incessantly indict The Economist.

The effects of all this could lead to mainstream publications simply refusing to review academic books in the future in fear that a similar uproar might emerge.

Before academics scream that a magazine is racist, consider how black civil rights activists strategized and theorized before they acted, how they did not just simply label every racist a racist, but worked to understand the roots of systemic oppression and then revolted against it--that is the half that has been told.