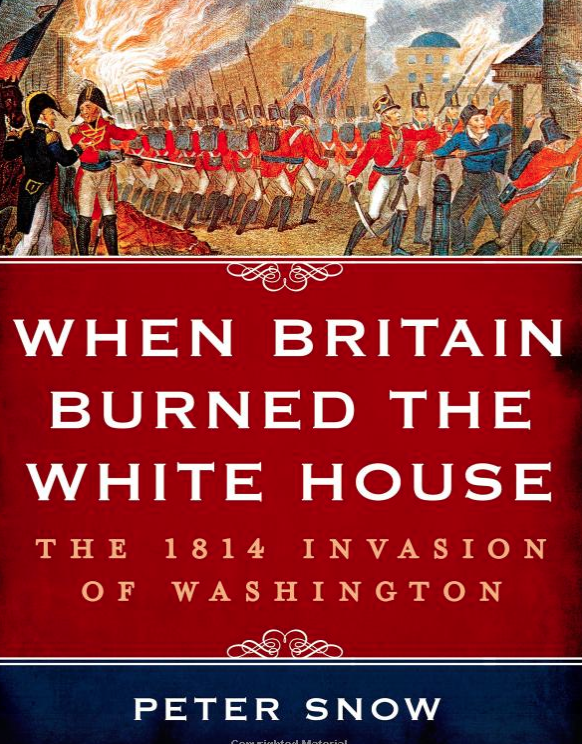

Why Did the British Try to Burn Down the White House?

When I speak to British audiences about my latest book – When Britain burned the White House – all but a very few express their astonishment that it ever happened. But that’s just what a small British force did to the American President’s mansion in Washington nearly 200 years ago. What’s more, hoping that their army would beat the British, President Madison and his wife had ordered a slap-up meal prepared for forty guests. Instead they found themselves fleeing for their lives.

When the British invaders in their bloodstained uniforms burst in to the White House, they found the table elegantly laid for dinner, meat roasting on spits and the President’s favorite wine on the sideboard. They tucked in with delight. One young officer said the President’s Madeira tasted “like nectar to the palates of the gods.” Afterwards he dashed up to Madison’s bedroom and swopped his sweaty tunic for one of the President’s neatly ironed shirts. One of his comrades bundled up the silver White House cutlery in the tablecloth. The British commander then calmly told his men to pile the chairs on the tables and torch the building. Before the night was done they also burned both houses of Congress, the War Office, the State Department and the Treasury.

It’s the only other time in US history – apart from the 9/11 terrorist attack - that outsiders have attacked the US capital. Just like President George Bush, who was airlifted to safety in 2001, James Madison, America’s fourth president, and his wife Dolley, were fugitives in their own country.

The attack on Washington was one of the most audacious military enterprises ever and the single most destructive act in the almost forgotten war of 1812. So what drove Britain to do it?

In 1812 the United States, a nation only some thirty years of age and poorly equipped militarily, declared war on Britain, the most powerful country in the world. It was a hot-tempered reaction to Britain’s interference with American trade with France and to the British navy’s arrogant forcible seizure of American sailors to man British ships. Britain for its part was fighting a war of survival with the French Emperor Napoleon. And when the US invaded British Canada and attacked Royal Navy ships on the high seas, London seethed with resentment. Enough troops were found to defend Canada, but the war effort in Europe precluded further action against the US for the first year. Then in 1813 a fiery Admiral, George Cockburn was dispatched with a squadron of Royal Navy vessels to cause what damage he could in Chesapeake Bay. He made himself deeply unpopular with a whole series of depredations in the small towns around the bay. But he was unable to do decisive damage to America so painful that the country sought for peace. It wasn’t till the summer of 1814 when Napoleon abdicated after his defeat by British force in Spain and Portugal and Russian, Austrian and Prussian forces in central Europe, that the British felt free to give the Americans what the British government called “a good drubbing.” A force of some 4,500 grizzled British veterans arrived on the coast of Maryland in August 1814. Cockburn was delighted and immediately suggested an attack on Washington. It would massively humiliate the American government, take the pressure off the hard pressed forces defending British Canada and avenge the American burning of the parliament in York (modern Toronto) a year earlier. What the British wanted was to see the American administration on its knees begging for peace. But that’s not quite the way it went.

There was indeed massive humiliation. James and Dolley Madison found themselves the most unpopular couple in the US in the aftermath of the burning of Washington. Mrs Madison, up to then the most popular first lady in America’s short history, found herself being thrown out of a house in Virginia where she and her husband sought shelter. The words of the owner – “Damn you Mrs Madison, if that’s you, get out of my house” – rang in her ears for years afterwards. It was one of the most shameful episodes in American history and James Madison was largely responsible for it. It had been his own incompetent appointees, War Secretary John Armstrong and army commander William Winder, who had lost the battle for Washington. On 24 August 1814 the British came near achieving their objective, which was to hurt the Americans so much that the war, which the British saw as a tiresome sideshow, would be brought to a quick end.

But America’s honor and her will to fight on were saved by another commander in another city. Baltimore’s General Sam Smith made a pledge to his citizens: “What happened in Washington will not happen here.” He guessed, rightly, that Baltimore would be the task force’s next target. And his prompt action and the courage of the men who defended Fort McHenry at the entrance to the city’s inner harbor restored America’s confidence and pride and rescued the President from utter disgrace. A young lawyer and poet, Francis Scott Key, saw to his astonishment and delight that it was not the Union Jack but America’s star spangled banner that flew over the fort at the end of the British bombardment. And the poem he wrote about the red glare of the British rockets that failed to destroy Baltimore’s defenses was one day to become America’s national anthem.

The war between Britain and the United States lasted only another four months with no real gains for either side. Both soon saw the endless tit for tat bloodshed and destruction as futile, and the peace that followed laid the basis for the special relationship between Britain and America that has lasted ever since. The two English speaking powers that had been bitter enemies became the closest of friends and never fought each other again.