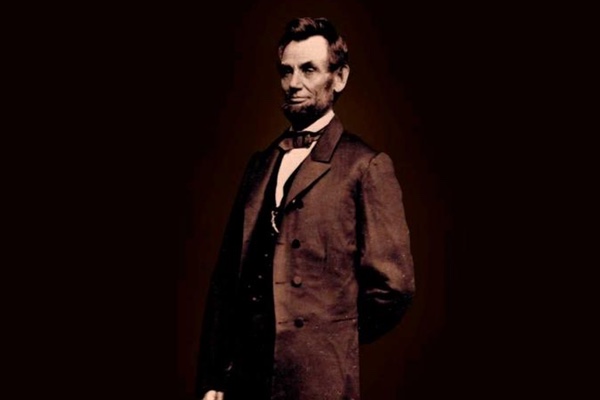

What Would Lincoln Do? Why this Is the Wrong Question.

While on a speaking tour for a new book on Lincoln recently, appearing in bookstores and museums and libraries from Washington DC to Mill Valley, California, one question has been repeatedly asked of me in venue after venue: What would Lincoln do? Of course, it isn’t phrased precisely that way, but the content is the same: If Abraham Lincoln were president today, do you think he would be striking ISIS? Would he endorse universal health care? What would be his policy towards immigration, privacy, campaign finance, global warming, gay marriage? Would he detain enemies at Guantanamo? How would he respond to the shooting in Ferguson, Missouri, to the outbreak of the Ebola virus? I usually beg off these pleas. Lincoln, after all, had a hard enough task determining policy for his own time, much less generating a blueprint for problems 150 years hence and, anyway, I am uncomfortable with such responsibility being thrust upon me, as if writing a single book about Lincoln makes me capable of channeling his thoughts. Still, there is something poignant in the repeated asking: Americans so desperately want someone to lead them, to make sense of the confusing world they inhabit, to impose sturdy values upon the confusing array of options before us. Who better than Abraham Lincoln?

The

fact that we so revere him today would have amused many in Lincoln’s

own day even – perhaps especially – Lincoln himself. He had been

elected in 1860 with the lowest voting percentage (39.8) of any

president in American history and it would be many years before he

would be etched into the nation’s consciousness as the savior of

the Union and the Great Emancipator, our most respected president.

Americans were judging him in the moment and many of them – in the

North as well as the South – judged him unfavorably. He had

disappointed his Republican colleagues and enraged his Democratic

opponents. He had been elected on a pledge to not disturb slavery

where it already existed; yet two years later, he issued an

Emancipation Proclamation freeing slaves in the rebellious states and

changing the mission of the war in what was for many, even in the

North, an unacceptable direction. Challenging constitutional

sensitivities, he had instituted the nation’s first national income

tax, suspended habeas corpus, and used the arm of the law to pursue

critics in the press. At a time when the constitutionality of

conscription was still undetermined, he had instituted the first

military draft, which included, remarkably, a provision allowing the

draftee to pay someone to take his place. That act alone contributed

to the worst civil violence in American history, the bloody 1863 New

York City draft riot. Indeed, in Lincoln’s time, looking back in an

attempt to capture their

historical heroes’ vision, people were asking, “What would

Jefferson do?” “What would Washington, Adams, and Madison do?”

And among those searching for the aura of the Founders was Lincoln

himself, who regularly cited them in an attempt to seize some

historical cover historical, for he certainly did not yet generate

any aura of his own.

The

fact that we so revere him today would have amused many in Lincoln’s

own day even – perhaps especially – Lincoln himself. He had been

elected in 1860 with the lowest voting percentage (39.8) of any

president in American history and it would be many years before he

would be etched into the nation’s consciousness as the savior of

the Union and the Great Emancipator, our most respected president.

Americans were judging him in the moment and many of them – in the

North as well as the South – judged him unfavorably. He had

disappointed his Republican colleagues and enraged his Democratic

opponents. He had been elected on a pledge to not disturb slavery

where it already existed; yet two years later, he issued an

Emancipation Proclamation freeing slaves in the rebellious states and

changing the mission of the war in what was for many, even in the

North, an unacceptable direction. Challenging constitutional

sensitivities, he had instituted the nation’s first national income

tax, suspended habeas corpus, and used the arm of the law to pursue

critics in the press. At a time when the constitutionality of

conscription was still undetermined, he had instituted the first

military draft, which included, remarkably, a provision allowing the

draftee to pay someone to take his place. That act alone contributed

to the worst civil violence in American history, the bloody 1863 New

York City draft riot. Indeed, in Lincoln’s time, looking back in an

attempt to capture their

historical heroes’ vision, people were asking, “What would

Jefferson do?” “What would Washington, Adams, and Madison do?”

And among those searching for the aura of the Founders was Lincoln

himself, who regularly cited them in an attempt to seize some

historical cover historical, for he certainly did not yet generate

any aura of his own.

That’s the frustrating thing about legends. We rarely recognize them in their own time because we cannot understand our times well enough to know what decisions history will celebrate and what decisions history will decry. We are, so to speak, too close to the painting to make out the contours of the image. Think of it. If history had ceased in 1938, Neville Chamberlain -- rolled umbrella confidently tucked under his arm, chin raised in a display of self-satisfaction, as he doffed his bowler to the adoring crowds – would have been a hero for achieving “peace in our time.” If time had stopped in 2003, with George W. Bush standing proudly in his flight suit atop the USS Abraham Lincoln (an appropriate detail, at least for this discussion) declaring “Mission Accomplished” on the war in Iraq, we would never have had to reconcile it with the scene going on now, as American F-22s rain bombs down on ISIS-controlled Syria and western Iraq. For that matter, if we roll back the clock only to December, 2011 with the departure of the last American soldier from Baghdad and the end of the U.S-Iraq Status of Forces Agreement, we would still be hailing President Obama for reversing the American tide toward foreign adventure that characterized his predecessor’s presidency, instead of nervously watching the Iraqi army that we funded, trained, and armed, fold under its first challenge, a sign that our earlier confidence that the Iraq war had been won, that the Iraq insurgency had been put down, and that political stability had emerged, was a mere fantasy.

The temptation to turn longingly to history’s heroes – whether recent or long-celebrated – arises from the evident truth that so many of our contemporary problems have their antecedents in, or at the very least correlations with, the problems of the past. Indeed, many of the decisions that Lincoln reached have powerful resonance with the issues of our own time. The clash with the Southern rebels produced plenty of terrorists and Lincoln treated them harshly, denying them due process; Lincoln injected the question of equality of peoples of difference into the American idea, though in his time it was race, not sexuality; Lincoln preferred negotiated ends to problems though war was thrust upon him even before he entered the office and after a period of hesitation and indecision Lincoln fought a hard war, a very hard war, convinced that rebellions need not simply be quelled but stamped out lest they rekindle. But those were responses keyed to his time. They do not necessarily tell us how to respond to ours. Even more important, we still cannot say with certainty that Lincoln chose the right path for his own day. Sure, the nation was saved and slavery was ended, but at what price? To paraphrase Faulkner, history is never history; it is always ripe for consideration and reconsideration.

Perhaps the prime thing we can learn from Lincoln is not what he did but how he did it, his deliberate method for decision-making which was characterized by the honest weighing of all sides to an issue, including the challenging of long held principles and assumptions before settling upon one inevitably imperfect plan. In a charming display of this approach, Lincoln once invited his friend Leonard Swett to the White House to listen to him read aloud the letters he had received containing all manner of arguments for and against emancipation. (Lincoln loved to read aloud for “when I read aloud I hear what is read and I see it” and thereby “catch the idea by two senses.”) The president then responded, also aloud, to each argument, both for and against, while Swett remained silent, his reactions never even sought by Lincoln nor provided. Lincoln knew what the choices were. He just wanted to project them into the air in the room so that they had substance for by doing that, maybe, just maybe, he would find a new clarity. Roughly a month after this scene, Lincoln issued the imperfect yet courageous Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation.

What would Lincoln do? Until they invent a computer program that allows us to construct his personality and then face him off against income inequality, Net Neutrality, and every other issue inconceivable in his time we can only absurdly speculate. But the real answer to that question is that it is not worth the pursuit. Our troubles are our troubles and they are ours to solve.