Can Scott Walker Win the Nomination by a Second Best Strategy?

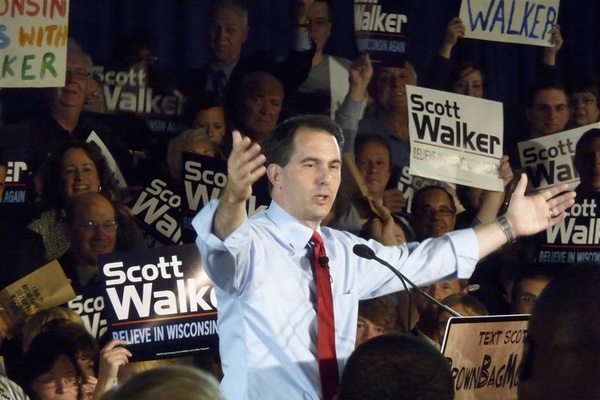

"Scott Walker primary victory 2010" by WisPolitics.com

Wisconsin Governor Scott Walker might be running behind GOP front-runners like Jeb Bush in the Republican primary polls, but his numbers show that he is moving up, coming in ahead of Ted Cruz, Marco Rubio, Bobby Jindal, Rick Perry and John Kasich in some polls. Recently, Walker made a case for his candidacy in the speech he gave at the Republican National Committee’s gathering in Coronado, CA. While he did not mention the other Republican hopefuls by name, he argued that the Republican Party needed an effective “fresh new leader” from outside of Washington whose ideas had been tested and had worked. Lest the GOP leadership have questions about it, he assured them that he actually liked to campaign and was good at it as demonstrated by his victories in two Gubernatorial elections and a recall in the blue state of Wisconsin.

This year, it’s anybody’s guess which candidate will get the prize. On the right, the party is split between many contenders, including Governor Mike Huckabee, Senator Ted Cruz, Senator Marco Rubio, Senator Rand Paul and former Governor Rick Perry. This situation may present Walker with a real shot at the nomination.

In Real Clear Politics, Catlin Huey-Burns makes a strong case for Walker’s chances. She writes that Walker is “carving out a spot now as Second Best, a candidate who can build consensus among voters seeking an alternative to the establishment or far right, who will be ready if and when a preferred candidate falters.” She adds that he is letting voters know that he is a “hybrid, capable of winning the hearts of the base and the minds of the center-right.”

The Second-Best strategy is not a new one. Warren G. Harding used it in 1920 to win the Republican nomination and then went on to a land-slide victory that November. Going into the convention, the two-front runners were General Leonard Wood and Illinois Governor Frank O. Lowden. Wood, who had been close to Theodore Roosevelt who had died the year before, now claimed to be his heir. He had organized the Rough Riders with the former President during the Spanish-American War, had been Chief of Staff for the U.S. Army, and had served as Military Governor of Cuba. Although Wood had the support of much of the party’s Progressive wing that had split away in 1912 and worked for TR’s “Bull Moose” party, he was a hard liner when it came to defeating the Bolsheviks and anarchists during the Red Scare, but had little political experience. Many of the Western Progressives were supporting Senator Hiram Johnson of California, a left-wing non-interventionist who was seen by many as a radical extremist.

The other front-runner was Governor Frank Lowden of Illinois, who had successfully turned the state’s finances around by reorganizing the state government, introducing a budget system, and lowering taxes. In 1919, he got nationwide attention for his role in dealing with the race riot in Chicago. Lowden supported the death penalty, women’s suffrage, and enforcement of the Volstead Act (prohibition).

Both Lowden and Wood raised significant amounts of money for their respective campaigns, which their supporters believed gave each the edge for victory but would be used against them. Wood’s campaign chest garnered $1,770,000, much of it coming from one wealthy contributor, Colonel William Proctor. Lowden, whose wife was a Pullman heiress, had a smaller but yet hefty sum of $415,000. In contrast, Harding ran his campaign with small contributions, ending up with a campaign war chest of $113,000.

Then, as now, a large campaign budget did not guarantee victory. In Lowden’s case, a Senate investigation revealed that one of his campaign managers had written checks to two convention delegates. The public considered it a bribe and many viewed Wood’s large expenditures in a negative light.

When the Republican National Convention convened in Chicago on June 8th, 1920, it turned out that after nine ballots, neither the two front-runners nor Johnson could get the votes of 493 delegates needed to win. Wood and Lowden’s delegates both refused to support the other front-runner and it was apparent neither could win. Fatigue set in, the delegates wanted to go home. Then Harding caught a lucky break when Lowden, who detested Wood, threw in the towel and told his supporters to vote for Harding. But even this did not ensure a Harding victory.

Behind the scenes, Harding was implementing a “second-best” strategy which his campaign manager Harry Daugherty and his staff worked around the clock to implement. According to Daugherty, their strategy was to “pass Wood with Lowden, and then build Harding’s vote from both until he won.” If a delegate could not or would not support Harding on the first ballot and if a deadlock indeed occurred, Harding’s people asked, would they consider voting for him on the second or even third ballot? Harding, as planned, increased his vote with each ballot taken, until the convention delegates realized that he was the best alternative; he came from the right state (Ohio), was well liked, and was acceptable to both the “Regular” and “Progressive” wings of the Party. Harding won on the 10th ballot, with 692 and one half votes.

Much of Harding’s success had to do with how he conducted himself. His philosophy was that it was more productive to make friends than enemies. For example, when Progressive Senator Miles Poindexter of Washington announced that he was entering the race for the nomination, Harding told his staff not to antagonize him, and he refused to campaign in Washington the way that Wood had campaigned against him in Ohio. Why antagonize a favorite son in his own state, he asked? Harding believed it would be better to not alienate him and the Washington delegates, so that he could secure “their support at such a time as they become convinced that he cannot be made the nominee.” Harding refused to attack his opponents personally, but based his campaigns on ideas and policies. He made a conscious appeal to all wings of the party, and sought to bring them together on behalf of a conservative program for the nation.

Harding, like Walker, was from a midwestern state, in this case, the indispensable state of Ohio which any candidate needed to win the presidency. Although he was a senator, he had business and management experience, having founded, edited and published The Marion Star for 25 years and had excellent relations with the press. He also had a midwestern “nice” personality, as does Walker, and easily got along with regular citizens who saw him as one of them. He enjoyed being among people and was an excellent campaigner.

Harding won his landslide victory because voters were tired of war and the depression that followed. They wanted a respite from the Progressive years and particularly what Harding and other Republicans called an era of Wilson’s one-man rule and wartime collectivism visible most clearly in the War Industries Board. On foreign policy, Harding rejected the U.S. entering the League of Nations on the terms Wilson sought, believing it would make the country subservient to foreign powers’ decisions on matters of war and peace. Yet he was not an isolationist, calling for the establishment of some kind of association of nations which would help to ensure peace. On domestic policy, Harding campaigned for lower taxes, reducing the extraordinary national debt that had been built up during the war years, reducing government spending, making the Federal Government more efficient and in general, putting the country back on the path to “normalcy.” The election results showed that is what the American people wanted too.

When the presidential vote was tallied Harding’s victory turned out to be greater than Harding and the Republican leaders ever imagined. He received 60.2 per cent of the popular vote,winning 37 of the 48 states, and capturing 404 of the Electoral College; compared to Democratic opponent James Cox’s 34 percent and 127 respectively. The Republicans also swept the House and Senate, giving them a 171 majority in the House and a 22 seat majority in the Senate.

Of course, circumstances are never the same. But any Republican candidate, including Scott Walker, will be running against Barack Obama and his Administration’s elitist progressive and crony capitalist agenda, which many American voters are fed up with. By presenting a positive agenda for the future, as did Harding, it is quite possible to beat Hillary Clinton, whose Wall Street ties and role in Obama’s administration make her vulnerable.

With a lot of luck and a careful campaign that unites all factions of the Republican Party around him, and as an alternative to the current “front runners,” Scott Walker just might be able to win using the “Second-Best” strategy that served Warren Harding so well.