Black and White?

From Trayvon Martin in Florida, Michael Brown in Ferguson, Eric Garner in Staten Island, to the recent killing of Tony Robinson in Madison Wisconsin: it is clear that the nation remains divided on race and bloodlines. In 1903, W. E. B. DuBois, founder of the NAACP, predicted that the problem of the 20th century would be the color line. If he were alive today I doubt he would be surprised that his prediction remains relevant in the 21st century.

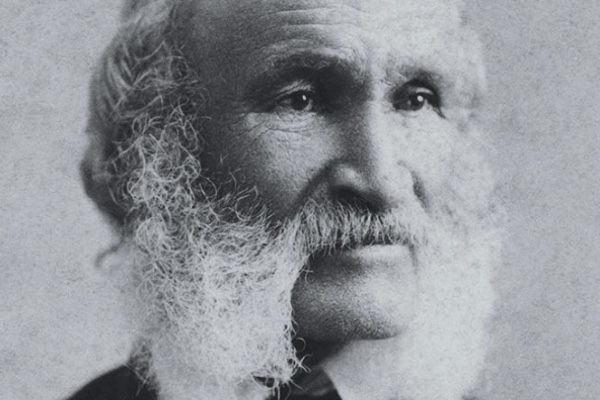

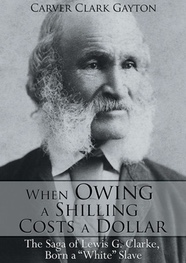

The story of Lewis G.

Clarke, my great-grandfather, a fugitive slave who became an

abolitionist, helps illustrate the complexity of the color line

problem.

The story of Lewis G.

Clarke, my great-grandfather, a fugitive slave who became an

abolitionist, helps illustrate the complexity of the color line

problem.

Clarke was born into slavery in Kentucky as the son of a Scottish weaver and a quadroon mother, and was separated from his family at the age of six. He became the slave of his wicked white aunt and half-sister of his mother. For over ten years for the slightest offense she would torture young Clarke daily with an oak club, a chair, shears, tongs, raw hide or anything else that was close at hand. According to Clarke, his aunt was typical among slave holding women in that she seemed to hate and abuse him all the more because he had the blood of her father in his veins.

Clarke was subsequently sold to two other slave masters, where his treatment somewhat improved. At the age of 25 he decided to escape from bondage after being informed that he was to be sold to a slave owner in Louisiana. In planning his departure Clarke intended to connect with his brother Milton rumored to have escaped to Essex County Canada and to free his youngest brother Cyrus in Lexington, Kentucky. He began a long, surreptitious sojourn all the way to Canada and back to Oberlin, Ohio and Lexington. His modes of travel were by foot, river barge, horseback, ferry, steamship and stagecoach. During the trek he suffered emotionally and physically, and avoided near capture by slave catchers unleashed by slave owners in Kentucky. After rescuing Cyrus and reconnecting with Milton in Oberlin, Ohio, word of Clarke’s suffering and dramatic escape spread among abolitionist leaders in Western Ohio as well as New York City and the Boston area.

Clarke was recruited to come North by Lewis Tappan, a wealthy founder of the American Anti-slavery Society. Under the auspices of the Society, Clarke established his residence at home of Aaron and Mary Safford in Cambridge, Massachusetts where he lived for most of the 1840’s. While there, he encountered Mary’s stepsister Harriet Beecher Stowe, author of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, published in 1852. Clarke’s experiences are evident in the great novel(Stowe later identified him as the prototype of the book’s rebellious octoroon slave George Harris).

While living in the Northeast, Clarke delivered over 500 speeches to audiences numbering in the thousands. His most significant speech, from a historical perspective, was probably his first in the North, delivered in Brooklyn beginning on October 20, 1842. Clarke spoke for three days. Lydia Maria Child, editor of the National Ant-Slavery Standard, captured the speech in an article, “Leaves from a Slave’s Journal of Life.”

While addressing the crowd, Clarke made this profound query: “My grandmother was her slave master’s daughter, and my mother was her master’s daughter and I was my slave master’s son, so you see I haven’t got but one-eighth of the [black] blood. Now admitting it is right to make a slave of a full black nigger, I want to ask gentlemen acquainted with the business whether because I owe a shilling [approximately 25 cents], I ought to be made pay a dollar?”

Clarke was never ashamed of his black blood. Nevertheless, his riveting question made abundantly clear the irrational, greedy and racist basis of the “one drop rule,” which meant anyone with a known black ancestor was considered black. One aspect of the rule certainly increased the number of available slaves and bolstered the burgeoning cotton economy to the benefit of slave owners.

Clarke’s question continues to be debated today among blacks and whites as to what constitutes race. Biologists unequivocally agree that racial categories have no scientific basis. Clarke was of the opinion, however, that the one drop rule, though fashioned out of ignorance and greed, united peoples having its origins from three continents, which could be proud of their customs and heritage as well as fight against slavery and racial injustice. I agree with Clarke’s perspective.

After Lewis and Milton escaped from slavery, each settled in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Milton remained there until his death in 1901, while Lewis moved on to New York state, Canada and ultimately back home to Lexington, Kentucky. Milton never considered himself black as did Lewis. He consistently made statements over the years such as “… somewhere a link was lost [in his linage] and a single drop of dark blood flows in my veins, but it is not discernable.” Like Lewis, Milton did not have prototypical black features. Milton married a white woman and they had several children. Newspaper and census records reflect that Milton’s children also never considered themselves black.

After Lewis’s death in 1897, the bloodline issue began to come to a head within Milton’s family. Jim Crow discriminatory laws in the late 1900’s along with the infamous Plessy vs. Ferguson “separate but equal” U. S. Supreme Court decision in 1896 reflected a greater backlash against blacks. Many individuals and families, who appeared to be white but had black blood in their veins, opted to crossover to the white world to avoid rampant discrimination. Such was the case concerning Milton’s family. His fear for his family is understandable.

The U. S. Library of Congress was in the process of gathering information on black authors and their books to appear as part of an exhibit in the planned Paris World’s Fair of 1900. Library officials wanted permission from Milton to have two books dictated and published by the brothers (Narrative of the Sufferings of Lewis Clarke (1845) and Narrative of the Sufferings of Lewis and Milton Clarke (1846) included in the exhibit. Milton refused and became so incensed by repeated efforts to contact him that he placed a copy of a court document in the Boston Globe in November 1900 prohibiting publication of stories related to the early history of his life because they may cause “annoyance and embarrassment to my children and relatives … except such facts as may be given out by my family after my death.” The decree was obviously an act of desperation. The story went viral and appeared in newspapers throughout the nation. Concern over the “one drop rule” clearly divided the families of the two brothers. My mother never mentioned Milton Clarke to me or other members of my family during her entire lifetime. However, as the result of research on my recent book, two years ago I connected with the great-great grandson of Milton and his family who, after more than 100 years never realized they had black blood in their veins. Our conversations are continuing.

A sad and sordid example of the one drop rule being still with us happened about a year or so ago when I was invited to attend a party given by a white couple I had known for a few years. The hostess introduced me to her son and his fiancé. I congratulated them on their engagement and began talking with the young lady. During the conversation she said, “I think you know my father.” She told me his name and I replied, “Of course, I’ve known Bob since high school days.” I was taken aback because Bob was a light brown skinned African American, who I heard married a white lady. His daughter did not in any way appear to have black blood. As the conversation continued it became clear to everyone in the conversation that her father was black. The future groom began to sweat and appeared uncomfortable. It was apparent that he had not met the young lady’s father. Less than a week later I was informed by a mutual acquaintance that the engagement was broken off because of the race of the young woman’s father. Appearance, by itself, may not bring about a racist reaction just knowing one has the “blood” may trigger the act. It was the young man’s loss because his former fiancé is very bright and attractive.

The tragic shooting of unarmed Tony Robinson, recently, in Madison, Wisconsin, and the protestations by the mother of the victim that her son was not black, but biracial, raises questions that are related to the one drop rule. Clearly, individuals have the right to identify themselves in any way they desire. That right must be respected. However, from looking at photographs of Mr. Robinson, I must say he had the appearance of many young men who also identify themselves as African American. A policeman, with a gun and a racist mindset who sees someone like Mr. Robinson will not go down a check list before determining if the suspect is African American, multiracial, mulatto etc. before he decides to perpetrate unjustified harm. He would see a man of color. I hope Mr. Robinson’s mother was not intimating a hierarchy of acceptability within racial categories. That certainly was the obvious intent when racial categories were first initiated in America.

When it comes to racial mixtures in the United States, 58 percent of African Americans have at least 13 percent European ancestry. Among those who identify themselves as white, 30 percent have some African ancestry. These figures show that we in America, both black and white, are more “family” than many of us are willing to admit. Taking into consideration the aforementioned statistics and antidotes, and as we see an increase of racial tensions swirling around us, raises this question: Are we as a nation operating within a paradigm of race and bloodlines that limit us from making greater strides toward racial harmony in America?