It’s 1815 All Over Again: The Troubling Tale of the Chappaqua Email Server

Keyboards are aflutter over the revelation that former U.S. Secretary of State and presumed Democratic presidential candidate Hillary Rodham Clinton (HRC) bypassed the State Department and outsourced her email management to a server located at the Clinton family home in Chappaqua, NY. It is a brewing storm in search of a scandalous name. Hillar-email-ageddon? Chappaqua-servergate?

Put aside for the moment the propriety of a Cabinet official engaging in these practices and let us explore why this cyber kerfuffle created potentially easy pickings for determined nation-state actors and put national security at risk.

Does anyone care about seemingly uninteresting tidbits from the world’s most powerful foreign minister? After all, as HRC has noted, the emails were not classified. Simple. Countries want to know the plans and intentions of friends and enemies, and they will take any scraps they can get.

To illustrate, let us wind the clock back to a time when one world power had no compunction about breaching protocol and spying on everyone’s diplomatic correspondence in a concerted effort to protect the security of the state and further its own political agenda.

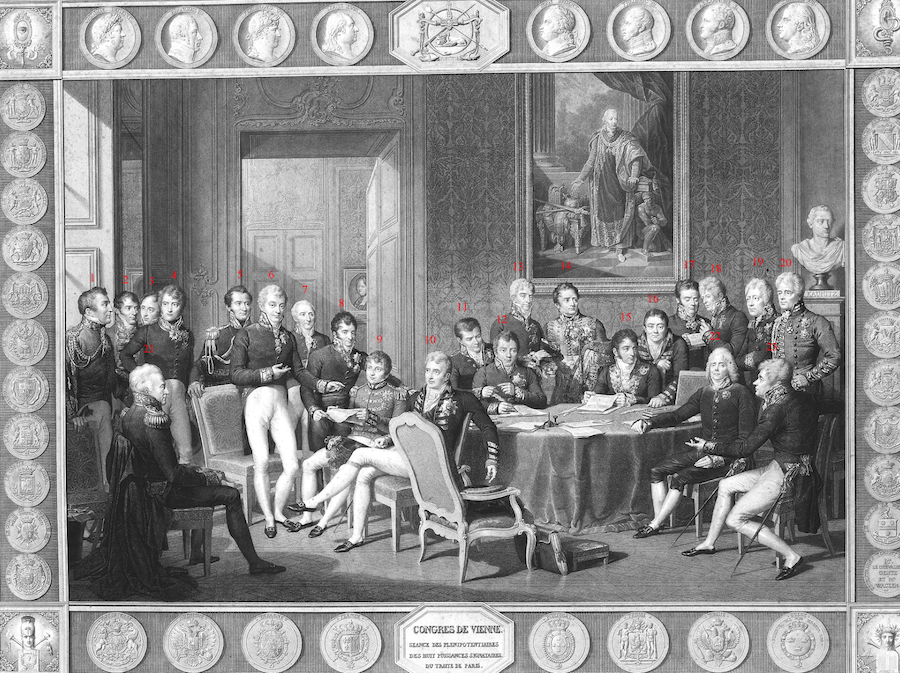

Exactly two hundred years ago, the European powers gathered at the Congress of Vienna to redraw the map of the Continent. The French Revolution had collapsed after a head-chopping reign of terror. Napoleon’s gallivanting across Europe was over. The aristocrats were back in the catbird seat and they were ready to party. For nine months from the official opening in October 1814 until June 1815, greater and lesser powers jockeyed for position as territories changed hands.

The secret police of the Austro-Hungarian Empire had been preparing for months for the delegates’ arrival. As the diplomats negotiated at the Congress or whiled away the evenings at fancy dinners and galas, the Austrian surveillance state was hard at work, following their every move. Secret police transcripts from the time run in the thousands of pages. No grain of information, however mundane, escaped notice and was dutifully transmitted to the Emperor’s desk.

The backbone of the Austrian spying program was reading diplomatic correspondence as delegates reported progress back to their countries (and threw in the odd bit of palace gossip and intrigue.)

Some diplomats tried to take precautions by sealing the envelopes with distinctive wax seals bearing their royal crests. Today we might call this using a weak password because the Austrian secret police could break the seals without leaving a trace. In secret bureaus, operatives employed special smokeless candles to pry loose the seals and, using metal putty, create perfect counterfeit replicas. The mail could be read, a new seal put in place, and the mail sent on its way as if it had traveled unmolested. Just like a man-in-the-middle attack works today for third parties who want to read your email and leave you none the wiser.

This worked until the nobles used new seals, which would be like changing your password to something easily guessable, and presented only a minor inconvenience to Austrian intelligence until new fake seals could be fabricated.

Some royals were too clever by half. Princess Theresa of Saxony tried to fool the watchers by giving the major diplomatic players nicknames in her letters home. The French foreign minister became “Krumpholz” and the Austrian was “Krautfeld”. Let’s call this very weak encryption, because with a little bit of work, a trained eye could engage in word substitution and figure out the puzzle.

Others went farther, writing in invisible ink between the lines of more innocuous letters. This is like strong encryption, but can still be broken with enough technical know-how. Prepared as ever, the secret police had chemical solutions to reveal the hidden text.

The Secretary of State’s email is like the diplomatic correspondence of two hundred years ago. As the Austrians had figured out, the connection of many innocuous seeming details could tell a story and provide indicators of an adversary’s intentions.

Imagine you intercepted a one-line HRC email to a staff aide: “Purchase Urdu phrase book by Fri” (not a real example). Might this indicate that a trip to Pakistan was imminent, signaling a change in U.S. foreign policy? India would certainly care about this, as would others with interests in the region.

Back at the Congress of Vienna, closely watching friend and foe soon overwhelmed the secret police. In addition to the four major political powers of the day, hundreds of advisors, courtesans, hangers-on and special interest groups had descended on the capital.

The surveillance net had grown too wide. It was impossible to shadow everyone and the decryption bureau was getting behind in transcribing letters, leading higher-ups to complain that the mail was being delayed. The intelligence service had what we might call a Big Data problem, and they had not yet evolved the analytical capabilities to make sense of all the information that poured in daily. Modern governments have many more resources at their disposal and can leverage technology to separate the wheat from the chaff, quickly doing the work that legions of clerks once did by hand, so vacuuming up all the data doesn’t necessarily create an undue burden.

Not everyone had his proverbial pockets picked at the Congress. One shining beacon of good information security practices emerges. The British Foreign Secretary, Viscount Castlereagh, though under the watchful eye of the Austrian surveillance state, frustrated their efforts to penetrate his information cocoon. In their internal reports the secret police privately complain that they cannot obtain any useful information. Castlereagh hired his own household servants, thwarting efforts to infiltrate his milieu with local agents. He further had his diplomatic correspondence hand-carried back to London and he ensured that all notes were completely burned in the fireplace.

Castlereagh’s good example from two hundred years ago shows us how these common-sense practices can still resonate today in the digital age, notably not sending sensitive information via unprotected channels and using electronic document shredding to erase proprietary information.

It is doubtful that the Chappaqua server had encryption to the standards of State Department diplomatic security. Yes, the HRC email server was behind a locked door. But information flowed in and out. As SecState, HRC was a million-plus mile flyer. Thus, of the tens of thousands of emails she penned while in office, we must reasonably assume that a significant number were sent from overseas before being routed via Chappaqua. From the WiFi hotspot at the airport VIP lounge in Beijing or Moscow perhaps? Who sits atop these access points to the information highway and sniffs the messages passing through? Answer: whoever wants to.

There are protestations that the HRC files were unclassified. But, as has been shown from the point of view of a two-century-old intelligence service (that didn’t even have the benefit of electricity), every bit can be part of a larger mosaic and exploited for all the wrong reasons. This tale of snooping during the Congress of Vienna would be an amusing bit of waltz-till-dawn diplomatic history if it weren’t such a stark reminder that in the digital age a country with enough resources and ill intent can use time-honored practices to exploit weaknesses in communications practices, read the mail, and make calculated adjustments based on what it learns. And that is why this episode has such disturbing implications.