Wanted: A Statesman for President

As news sources are now bellowing, the presidential campaign season has arrived once again—starting way too early and allowing candidates of all stripes to begin their pitch for vague short-term fixes while pandering to special interests and social and religious issues. Voters have a generally negative view of our politicians for this reason and their inability to solve problems. But they bear blame, too, because these same voters reward those addressing the most current itch instead of those focusing on solutions to larger, long-term problems. Good governance generally centers on solving the biggest and most important problems first, and taking the long view in the process of doing so. While the benefits of sound policy take time to manifest themselves, voters rarely have much patience for such solutions. But history shows us what lasting benefits great statesmen can produce with the proper focus.

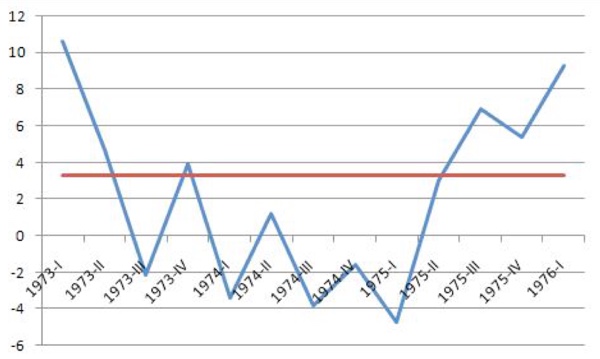

A lesson in the benefits of stellar leadership is currently playing out each day, as financial news tracks the next step by the Federal Reserve Board regarding interest rates. The Fed has not always been the carefully deliberating body that attempts to optimize the mix of full employment against the ills of inflation. After the Great Depression, the Fed’s exclusive focus was on maintaining full employment. And in the post-World War II boom years, that generally worked well. Then, after the guns and butter Lyndon Johnson years coupled with the OPEC oil price increase, inflation began to accelerate out of its old moderate range. President Richard Nixon pressured his Fed Chairman, Arthur Burns, to steer an easy money policy to keep the economy rosy, but then tried to tame rising inflation with ineffective and disruptive wage and price controls and gas rationing. When Nixon resigned, inflation was roaring upward through 12 percent (see St. Louis Fed’s CPI data). At the time, many economists led by Milton Friedman, asserted that the Fed’s easy money policy supporting full employment was the primary cause of accelerating inflation. Politicians, however, feared that tightening the money supply would drive up interest rates and unemployment and cause them to be voted out of office. Fear trumped valor and good, long-term policy. Many financial professionals conceded that politics would never allow corrective action on inflation.

It would take someone with a long view to administer a cure. As historian Yanek Mieczkowski describes in his enlightening 2005 book Gerald Ford and the Challenges of the 1970’s, President Ford was fond of saying that “politicians are focused on the next election, statesmen are focused on the next generation.” In a courageous move, Ford allowed Fed Chairman Burns to pursue a tight money solution regardless of the potential for recession that rising interest rates would induce. By the end of Ford’s short 28-month term of office, this policy brought inflation down more than 6 percentage points, and, while the policy exacerbated an ongoing recession, the country was well into a healthy recovery. (Pundits who laughed at Ford’s Whip Inflation Now PR campaign, foolishly overlooked his ground-breaking monetary policy results.)

US GDP Growth Rates

Short-sighted voters ignored this spectacular economic achievement and replaced Ford with Jimmy Carter, who professed his preference for a return to an employment-focused Fed policy. With the same Fed Chairman who served under Nixon and Ford, inflation then ramped up again to more than12 percent by the end of Carter’s single term, despite the appointment of Fed Chairman Paul Volcker in August 1979. Myopic voters had unknowingly opted for a second bout of double-digit inflation and stagnant growth (“stagflation”) by rejecting Ford. Most observers forgot the inflation cure administered during the Ford presidency because it was reversed under Carter.

But Paul Volcker, freed from Carter’s directives, and the new Reagan administration remembered. In league with Milton Friedman, they quickly copied Ford’s medicine of tight money policy and cautious fiscal policy, figuring that they had nearly four years to weather the storm of an inflation-flushing recession. True to form, voters reacted wrathfully to the resulting 1981-82 recession by hammering Republican congressional candidates in the 1982 mid-term elections. However, they rewarded Reagan and the Republicans in the presidential election in 1984 as the recession faded from memory and inflation declined. Copy-cat Volcker’s results were almost a mirror of those attained under Ford—about a 7.5% drop in inflation over 2 years. And the copy-cat walked away with all the credit as many countries around the world followed “his” prescription.

President Ford had a lifelong interest in economics, enhanced by his many years’ service on the House Ways and Means committee (a good trait to look for in the next President). So his ability to understand and support sound economic policy by the Fed was no fluke. Supporting this point was Ford’s prescient work with the President of France to start the G7 economic summit meetings, which recently concluded. At the time, the need for global economic cooperation on this level was far from most people’s minds. But not for the statesman Ford.

Today, we benefit from Ford’s focus on long-term policy every time we hear Fed Chairman Yellen pronounce her twin focus on employment AND inflation. The inflation of the 1970s, among other things, decimated the value of retirement savings for millions of Americans. Today, the nation, especially the growing retirement community, should thank their lucky stars for statesmen like Ford and pray that we haven’t seen the last of them (and a more thoughtful electorate) in coming elections.