Why Can’t We Even Talk About Abortion?

These past few weeks have been grisly. Videos of casual conversations over lunch about selling fetal body parts, crushing skulls to preserve organs, and tiny human pieces in a bloody lab dish.

And I can guarantee you that the way I just opened this op-ed has caused more than half the people reading to stop, thinking that I am some nut-wing, pro-lifer. We have gotten to the point where we cannot even have a civil discussion about abortion. It is a subject that is off limits. Taboo.

I confess I stopped thinking about the

issue in the 1970s after Roe v. Wade was decided. I was

squeamish about abortion but like a good liberal Democrat I believed

I was (my great-grandfather was the register of the Treasury in FDR’s

administration), I agreed with the thinking that this was an issue

that was personal and each person should have the right to choose how

to plan a family. I was probably like most moderate Americans:

anti-abortion, but pro-choice.

I confess I stopped thinking about the

issue in the 1970s after Roe v. Wade was decided. I was

squeamish about abortion but like a good liberal Democrat I believed

I was (my great-grandfather was the register of the Treasury in FDR’s

administration), I agreed with the thinking that this was an issue

that was personal and each person should have the right to choose how

to plan a family. I was probably like most moderate Americans:

anti-abortion, but pro-choice.

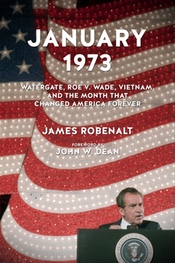

When I decided to write my most recent book, January 1973, Watergate, Roe v. Wade, Vietnam, and the Month That Changed America Forever, that all changed. I had to look at the issue without blinkers and try not to take sides. The first thing I needed to find out was: how did the Supreme Court decide Roe v. Wade? What was the decision process?

I had the extraordinary opportunity to interview Justice Lewis Powell’s law clerk from the time. He now lives in Arizona and agreed to speak with me, telling me that Powell had released him to talk about his interactions with the justice, as long as he did not speak about other members of the Court.

Turns out, this law clerk is the person who brought to Powell the concept of “viability,” which is the hallmark of Roe. My source was in a sense the silent author of Roe v. Wade, because it was Justice Powell who convinced Justice Blackmun to set the marker of viability as the point in a pregnancy before which a state could not prohibit abortions. In 1973, viability was basically after the second trimester, or six months into a pregnancy. It was the time when a fetus could live outside the womb. Medicine has moved that marker some, but it still remains the critical turning point, mainly because of fetal lung development.

Attempts to undo the viability standard and Roe have failed, although the law has changed in allowing regulation of how abortions are performed (who can perform them, the age of informed consent, what facilities can be used).

But not long after Roe was decided in 1973, the battle lines formed and hardened. Religion became a major force in federal politics. I argue that January 1973 can be seen as the genesis of our modern “no compromise” government, mainly because of Roe but also in part as a result of the Nixon counterrevolution and political party realignment he so skillfully navigated. “No compromise” found its way into our political bloodstream.

What I have noticed, though, in discussing my book is that the subject makes people very uncomfortable. I can see a door shutting behind the eyes of a listener within minutes of the start of a conversation about abortion. It is both a protective reaction and a political reaction: don’t go there. I have my views, the reaction seems to say, and don’t even try to talk me out of them. I know this is complicated and I don’t want to think too much about it.

On the one side—the pro-choice group—this is an issue about women’s autonomy. They instantly talk about “women’s health” and how those opposing abortion are anti-women and religious zealots.

On the other side—the pro-life group—this is a life and death issue, one that is not subject to compromise. They instantly talk about “murder” and how cavalier and inhuman their opponents have become.

The conversation does not advance beyond name-calling and recitation of pat slogans. When I posted on Facebook an article from the New York Times on the Planned Parenthood videos, two people I did not even know got into it.

“It's simple, if you don't like abortion, don't have one,” one reader, Jeremy, wrote.

The reaction was swift from someone named Julie: “Yes. I would say that thought process is indeed ‘simple.’ Don't like murder, don't commit murder. Don't like abuse, don't abuse. Don't like robbery, don't steal. There! We've solved it all! Genius.”

“Tread lightly, Julie” Jeremy responded, “you don't know me. Abortion is something you choose to have. Murder, abuse, and robbery are all things one does to others. Big difference genius.”

“Dismemberment of a human is a hideous, barbaric crime committed against another,” Julie replied. “Those hearts, kidneys, arms and legs being sorted for research do not belong to the mother. 60 million is a big number. My apologies Jeremy for being so rude. Pushed to the brink by this discussion elsewhere and took it out on you. I just don’t think we can look away any longer and say live and let live.”

These two are not the only ones who have trouble discussing this issue. Hillary Clinton called the videos “disturbing” and asked for some sort of investigation, but she could not condemn Planned Parenthood. Elizabeth Warren derisively asked her colleagues in the Senate if they had been knocked on the head and woke up in the 1950s or 1890s. She characterized proposed legislation to defund Planned Parenthood as "just one more piece of a deliberate, methodical, orchestrated, right-wing attack on women's rights. And I'm sick and tired of it."

Joe Scarborough of MSNBC’s Morning Joe responded to Warren: “Please stop insulting our intelligence, Elizabeth Warren. Stop.”

There is no doubt it is hard to have civil discussions these days about many political subjects, but abortion is unique. There is so much riding on it for many of the true believers on both sides that even a thoughtful discussion is not in the cards. And the problem is most of us need to have a civil discussion. We lean towards one side or the other, but we can understand why people feel differently—and we would like to see a sensible solution after a strong public debate.

The Supreme Court caused some of this problem, inadvertently. I know from my study that the justices in January 1973 were concerned about poor women, young women, and confused women who found themselves pregnant. Unlike women of means and maturity, these women did not have safe options to end an unwanted pregnancy. So the line was moved internally at the Supreme Court from a cutoff after the first trimester (first three months) to viability because of the fear that inexperienced and poor women wouldn’t have the time to avail themselves of an abortion if they had to do so within the first three months. Many would not recognize they were pregnant, or would be slow to admit it to their families, boyfriends or husbands.

The Court justices who decided Roe v. Wade thought they were ending the debate for good, and for the right reasons. But it need not have been this way. State legislatures had already started to react—New York, for example, had just passed a reform statute out of the legislative process. With Roe taking the issue out of the hands of legislatures, many voters felt disenfranchised about the issue, causing them figuratively to take to the streets. There was no room for discussion; this became part of the “culture wars” we have been fighting for the last 40 years.

It has been a stalemate ever since. The thing we need in this conversation is a conversation. We need to listen and empathize with our opponents and treat abortion as a question that requires intense thought and debate, not one that provokes kneejerk reactions.

I do not profess to have a solution. I tried to write my book in a neutral way. But I do know that our democracy only works when we listen and compromise. Reasoning together is the only way out of this impasse.