The Glory Days of Tough-Guy Writer Ernest Hemingway

I thought writer Ernest Hemingway was long gone from public memory, trundled off on the literary train to nowhere, an ancient relic of the days of sparse, pungent, emotional, gritty writing that does not exist anymore. Today, literature is filed with stories of men trying to find themselves, young women participating in Hunger Games, countless sordid murders, diet books and stories about an endless army of aliens headed towards Earth or already here. Hemingway wrote about tough men drinking themselves under the table, catching huge marlin on the high seas, shamelessly chasing women, soldiers firing cannons, wars, sailing through tropical storms, climbing mountains and fist fights. He was older than old school, gone, forgotten, yesterday’s news, on the dusty shelves at the back of the library.

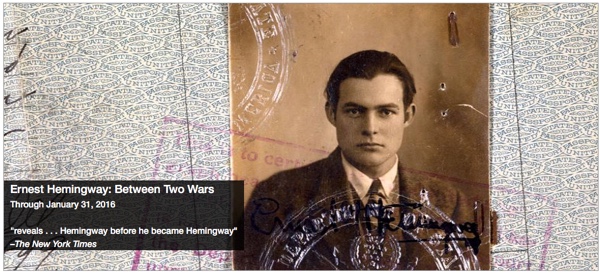

When I walked into the Morgan Library and Museum in New York on a quiet, breezy Sunday morning to look at their new exhibit on the writer, “Ernest Hemingway: Between Two Wars,” I did not expect to find many people there and, if I did, they would all be senior citizens who grew up with him in the 1950s.

Was I ever wrong! The library and museum, with is enormous rooms and high vaulted ceilings, was packed and I had to wait on a line to get in. The Hemingway gallery was jammed with people, and they were not senior citizens either. There were dozens of college students, women with scarfs wrapped around their necks and boys staring at their Blackberrys, and young men and women who looked like they hard worked terribly hard all week. There were New Yorkers, other Americans and tourists from Europe and other continents. I was shocked at how popular the bearded, macho-man writer, author of The Old Man and the Sea, The Sun Also Rises, A Farewell to Arms, The Snows of Kilimanjaro and so many other works, remains. The author blew his brains out a long 55 years ago, but is surprisingly popular today.

The exhibit is highlighted with a wonderful, six-foot high photograph of Hemingway on crutches after being injured in World War I. It is divided into six sections, each telling a part of his life, starting at the end of the first Word War. It ends with Hemingway as writer and sportsmen in the 1950s and his 1960 death. It is loaded with old documents (didn’t this guy throw away anything?), including his letters, magazines, passports, telegrams and even ticket stubs to bullfights he attended in Spain as part of his research on the novel Death in the Afternoon. There are photos of him, his wives and his friends.

There are two major surprises in the exhibit. First, he and F. Scott Fitzgerald, author of The Great Gatsby, were very close friends. History has portrayed them as literary enemies who constantly sniped at each other, but that was not so. Fitzgerald was not only his friend, but read his work and suggested changes, some of them major, that Hemingway made. The other surprise is how many revisions Hemingway did on just about all of his fiction work. He redid entire paragraphs half a dozen times until he got it right. He dropped whole chapters that he did not like, or that others did not like, from his books. Someone told me that he rewrote the last page of the The Sun Also Rises 19 times and now, having seen his work, I believe it.

Hemingway wrote almost all of his stories in long hand on paper and rarely typed them out. Most people believe he labored over the typewriter because so many book jacket photos printed in later years featured him with a typewriter. The library exhibit has dozens of marvelous original drafts of his short stories and books, old ink leaping off the page at you, many with paragraphs heavily edited or trimmed from the text

Hemingway got started as a writer when he was badly injured while working as an ambulance driver in World War I. He wrote some fiction stories based on his experiences, and created a character, Nick Adams, who appeared in many of his short stories. Earlier, he had worked for the Kansas City Star, where he learned to write tight stories with few adjectives. He made that sparse style his hallmark, and it such a hallmark that for years after his death people participated in Hemingway write-a-like contests (there is an annual Hemingway look-alike contest, too).

He had a strange and wondrous style of writing. All of the young writers working in the World War I era were trying to find a style “It was the era of trying to use words,” wrote poet T.S. Eliot.

Hemingway himself stuck to his own ideas. On writing, he tried to “make it seem normal, so that it can become part of the experience of the person who reads it.”

People loved him and enjoyed his spartan style of writing with its explosions of both action and color. One friend who knew of his love of both action filled writing and boxing, mirthfully referred to him as “Kid Balzac”

Hemingway loved to cover battles and was as happy in World War II as he had been in the First World War. “War is the best subject of all,” he said. “It brings out all sorts of stuff that normally you have to wait a lifetime to get.”

He wrote on any paper he could find, once grabbing a thick pile of empty sheets of telegraph paper at an office and scribbling pages of a short story on the pages, faded now after all these years.

Dorothy Parker called him “a truly magnificent writer “ and critic Edmund Wilson wrote of one of his novels “your book is a knockout, the best piece of fiction that any one the new crop of Americans has done.”

Surprisingly, there has never been a full library exhibit of Hemingway. “It is impossible to talk about the history of twentieth century American literature…or world literature for that matter…without talking about Ernest Hemingway early in the conversation,” said Morgan Library director Colin B. Bailey. ‘His novels, such as The Sun Also Rises, A Farewell to Arms and For Whom the Bell Tolls are among the best known and acclaimed books of the modern era.”

The exhibit moves quickly to the streets (and bars) of Paris. Hemingway loved Paris and moved there in the early 1920s. He befriended Fitzgerald, John Dos Passos, Gertrude Stein and others. He was one of the writers who coined the famous phrase “the lost generation” of post World War I men. There he became part of the literary set, dining and drinking with other writers, personally closing half the bars in Paris, as he wrote several novels and short stories.

An interviewer once asked him if something happened in his life that made him a writer, or if at some particular moment in his life he decided to write. He looked at him blankly. “No, I always wanted to be a writer,” he said.

He was noticed right away. When his book In Our Time was published, a critic for the New York Times wrote that “his language is fibrous and athletic, colloquial and fresh, hard and clean, his very prose seems to have an organic being of its own.”

Hemingway left Paris with his wife Pauline in 1929 and took up residence in Key West, Florida, where he wrote A Farewell to Arms. Later, they divorced and he moved to Havana, Cuba, where he stayed for years, wrote more and became quite a well-known deep sea fisherman (he caught a 465 pound marlin that was a record at the time). He was divorced, married Martha Gellhorn, another writer, and moved to a farm house outside of Havana with her. He wrote numerous short stories for large magazines in the 1930s and traveled to Spain to cover the civil war in that country His experiences there became the basis for one of his great books, For Whom the bell Tolls.

When World War II started, Hemingway was back in Europe covering it. "I got war fever like the measles,” he said.

His writing slowed down in the early 1950s, except for The Old Man and the Sea. He died in 1960.

There are some weaknesses in the overall wonderful exhibit. Hemingway was famous for chasing women and for his many wives, but other than a few photos, you learn very little about his relationships with women. The exhibit has a lot of pictures, but they are all small. It needs some large, oversized photos of Hemingway, or posters of bullfights or places to where he traveled. Some of the stills from movies based on his books, like the film The Snows of Kilimanjaro, should have been blown up and mounted on the walls. The Old Man and the Sea was a very famous movie and has appeared frequently on television, yet there is little in the exhibit about the book or film. Just one big Old Man and the Sea photo or poster would have been nice. There might have been some of Hemingway’s fishing tackle, purchased in New York City, or one of his desks. How about a lot of photos of all the cats that lived with him in Cuba?

Would the great writer liked to have been remembered like this, held in such high esteem in one of the country’s finest libraries? No. He’d rather be remembered out there on a boat in the wide, blue ocean, looking for the big fish, a can of beer held firmly in his hand.

The Library is sponsoring a film and lecture series to accompany the Hemingway exhibit. It has screened already screened the films To Have and Have Not and The Killers, based on his books. It will host a concert, Cygnus Ensemble and Hemingway, featuring music of Paris in the 1920s, when he lived there, on December 8. Throughout the fall, there will be several gallery talks on the exhibit and his works.

The library’s gift shop is overloaded with Hemingway novels and biographies. They are selling a Hemingway ‘how to camp out’ booklet and even a book on Harry‘s Bar, the Venice watering hole made famous in Hemingway’s works.

* * *

The Morgan Library and Museum is located at 225 Madison Avenue (at E. 36th Street), New York. The exhibit will be there through January 31, 2016.