We’ve Just Learned the Origins of Illegal Surveillance in the United States Go Back to the 1930s

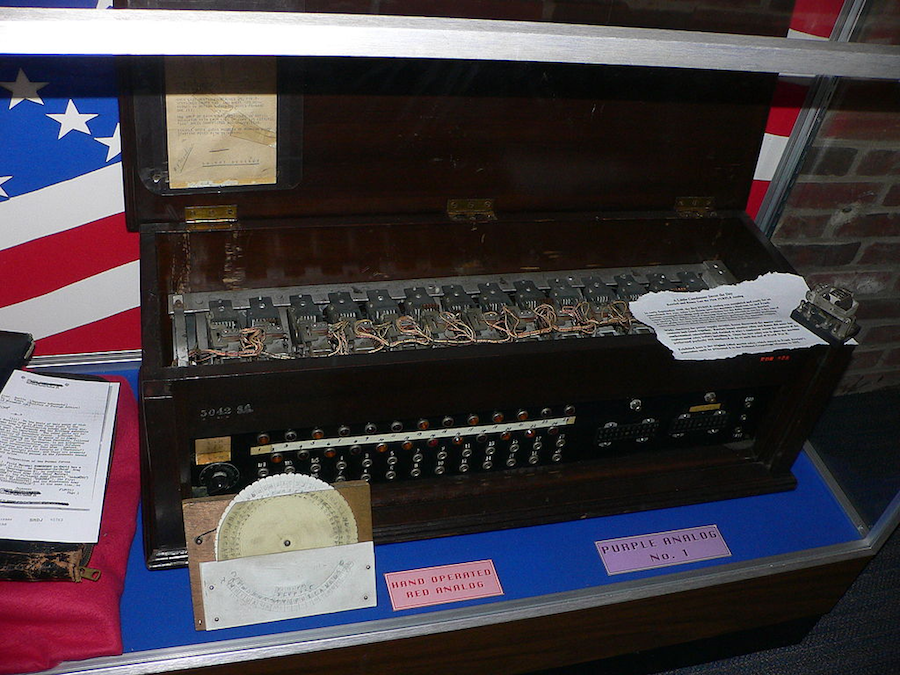

Image by Mark Pellegrini (Own work) [CC BY-SA 2.5], via Wikimedia Commons

Half a century before either Edward Snowden or Chelsea Manning was born, American military codebreakers and U.S. telecommunications companies collaborated on a secret electronic surveillance program that, as newly declassified documents reveal, they knew to be illegal. The program, approved at the highest levels of the U.S. government, targeted messages sent by foreign embassies in Washington, DC, in the years leading up to World War II, and was dramatically expanded after the war.

In a series of oral history

interviews recorded in January 1976 by the National Security Agency for

internal use, Frank Rowlett, one of the most celebrated American cryptologists,

described how the Army Signal Intelligence Service (SIS), which eventually

became the NSA, systematically collected copies of cables sent by foreign

embassies in Washington during the 1930s. Transcripts

of the interviews were classified "Top Secret" until they were

declassified this year.

In a series of oral history

interviews recorded in January 1976 by the National Security Agency for

internal use, Frank Rowlett, one of the most celebrated American cryptologists,

described how the Army Signal Intelligence Service (SIS), which eventually

became the NSA, systematically collected copies of cables sent by foreign

embassies in Washington during the 1930s. Transcripts

of the interviews were classified "Top Secret" until they were

declassified this year.

While the SIS's access to diplomatic cables has been known for a long time, the Rowlett interviews reveal something new which is of particular interest today. An NSA historian asked Rowlett if SIS or Army intelligence had given any thought to the legality of using cable traffic after enactment of the Federal Communications Act in 1934, a law that clearly prohibited the interception of any interstate or foreign communication by wire or radio. His answer was unequivocal: "Yes we gave considerable thought to it. We knew it was illegal and therefore we better keep quiet about it."

SIS personnel came up with an interpretation of the law that made intercepting and decrypting cables legal, but Rowlett made it clear that they didn't fool themselves into believing that this interpretation was correct. "Essentially we recognized its potential illegality and we knew if it ever got to court that we would be condemned and even some of us might be tried as individuals," Rowlett recalled. "We were told that the law was unfair, that this was being done in the national interest and if we had any qualms about it we better get out because if it ever came to [an] issue [of] the law, the legal aspects might be against us."

Executives in Western Union, RCA and other cable companies also knew they were breaking the law. They cooperated with SIS because they "felt like they were doing a national service and were proud to be involved in this thing," Rowlett said. Senior executives at the cable companies who participated in the covert operation had been persuaded that it was "in the national interest" and that the information collected would be used for legitimate purposes, Rowlett said. These executives were careful "to make sure that whatever arrangement was set up … could be kept secret and not leaked to the press."

Surveillance of electronic communications was just as controversial in the early decades of the 20th century as it has become in the Internet era.

In 1929 Secretary of State Henry Stimson famously asserted that "Gentlemen do not read other gentlemen's mail" and shut down the State Department's "Black Chamber" codebreaking operation. This has been widely, and erroneously, interpreted to mean that America got out of the business of spying on the communications sent and received by potential enemies and allies in 1929. In fact, within a few months of that statement, the Black Chamber files had been shipped to the Army, where a small cadre of codebreakers was busy recreating and expanding its operations.

Rowlett was one of a handful of men – and a few women – who built America's capacity to create secure communications, and to break the carefully constructed codes and ciphers that protected the secrets of foreign nations. Rowlett described himself as a "country boy from Rosehill, Virginia" a dust speck situated a few miles from the Kentucky and North Carolina borders. When he was hired by the SIS on April Fool's Day, 1930, he didn't know what cryptanalysis was.

Rowlett learned quickly, and by 1935 he was part of an SIS cryptanalysis team that broke the Japanese diplomatic code, which was produced by an electromechanical machine the Americans called Red. In 1939, the Japanese replaced Red with a deviously complex device the Americans called the Purple machine. The Japanese were confident that Purple was absolutely secure, and many of the world's best cryptanalysts also felt that the system could not be defeated.

It took Rowlett and a small team only 18 months to create a replica of Purple, even though they had never seen one of the machines, and to gain the ability to rapidly decrypt high-level Japanese diplomatic communications. It was a triumph of the intellect, later dubbed by the NSA "the greatest feat of cryptanalysis the world had yet known." Purple gave the United States the ability to peer over the shoulders of Japanese diplomats around the world as they received instructions from Tokyo in the autumn and early winter of 1941.

On December 3, 1941, SIS decrypted a Purple message from the Japanese Foreign Ministry instructing its embassy in Washington to destroy all but one of its code machines. An astute intelligence officer, Colonel Otis Sadtler, immediately grasped the significance of the instructions, Rowlett recalled. "No government is going to destroy its codes unless it is going to go to war," Sadtler said, as he literally ran to sound the alarm. A subsequent Purple decrypt, received on December 6, removed all doubt. It stated that Tokyo planned to break diplomatic relations with Washington.

The Japanese continued to use Purple machines throughout the war. The Japanese ambassador to Berlin used the cipher machine to convey information, including news about German military plans, to his superiors -- and unwittingly, to the U.S. military. Purple decrypts also revealed Japanese efforts in 1945 to persuade Stalin to act as an intermediary in peace talks with the United States and Great Britain, revealing that it would surrender only if it was allowed to keep the Emperor on his throne.

After the war, telecommunications companies continued their covert collaboration with the Army and, after its formation in 1952, NSA. This collaboration grew into Operation Shamrock, a vastly expanded surveillance project under which every international telegram originating in or traveling through the United States was turned over to the NSA. One of the reasons the spying continued long after the shooting was over, Rowlett's oral history interviews reveal, is because NSA worried that if companies ever stopped they might not be willing to resume illegal spying. He noted that "it had been a very nervous thing to get these companies involved in this activity earlier and we felt if they ever pulled away from it that we might not be able to recruit them to assist us."

When Operation Shamrock was publicly disclosed in 1975, Americans were shocked by the magnitude of the NSA's surveillance, and the agency quickly shut it down.

With the clarity of hindsight, the U.S. Army's decision to illegally collect encrypted cables in Washington in the 1930s, and the equally illegal collaboration of the cable companies, was certainly justified. If the Army had waited to start working on Purple until the declaration of war, the solution would not have come until the middle of 1943 -- at the earliest -- and, given the competing priorities, it might never have been achieved.

This raises important questions. Will our grandchildren, looking back 70 years from now, conclude that the massive domestic surveillance operations of the Cold War, and those launched after 9/11 were justified? Did America's intelligence agencies learn the wrong lesson from the illegal interception of diplomatic cables in the 1930s, institutionalizing a disregard for the law that inevitably led to excesses?