How Hofstadter and Schlesinger Misled Us About FDR: An Interview with Eric Rauchway

Related Link An interview with Eric Rauchway on the Freudian roots of the right's love of the gold standard

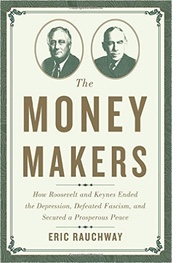

Q: You’ve written a book about what you call “Roosevelt’s dollar.” What is that, and why do you want to write about it?

The dollar we have today is the one Franklin Roosevelt created as a tool for recovery from the Depression and as a weapon to fight fascism; these were aims he saw as closely linked, and often essentially the same. I think we would use that tool, and that weapon, better now if we properly understood its original purpose.

Q:

Say a little more about that. What do you mean, “original purpose”?

Q:

Say a little more about that. What do you mean, “original purpose”?

Well, from slightly before Roosevelt first took office in 1933 he knew that the principal task of his presidency was to fight fascism, both inside and outside the United States. It was a fight that lasted his entire time in office. So all his policies, even the recovery policies of his first term, need to be seen in that light: he was seeking recovery not only from the worst economic downturn in history, but from the kind of economic downturn, the Depression, the deflationary spiral, the precipitous drop in prices and crippling rise in unemployment, that led to Hitler gaining power in January 1933. At the time Roosevelt took office in March of that same year, it looked very much as though unless something happened quickly to reverse the downturn, the US faced a very real threat of mass revolt, which might well put a fascist regime in power.

So he had to arrest the downward plunge of prices, and he did that, with his first action on taking office, which was to take the dollar off the gold standard and, as he said at the time, move the US toward a permanent policy of managing the value of its currency so that no such crisis would ever occur again.

Moreover, at the same time, he said this managed dollar should be part of an international system of managed currencies, so that all countries could similarly use monetary policy to prevent economic crises and political turmoil. Which is where his presidency ended up, with the establishment of the Bretton Woods system of fixed-but-adjustable currencies in 1945.

Q: That’s not the view we usually get of Roosevelt’s policy in 1933, though. Traditionally, historians refer to his monetary policies as nationalist at first, then moving gradually over the course of his twelve years in office to a more internationalist framework.

Right, well, if I thought the traditional view was correct I wouldn’t have written the book, I guess. I think traditionally, historians have gotten this wrong for a couple reasons.

First, it’s based on an unearned reliance on the earliest memoirs covering Roosevelt’s currency policy by people who strongly opposed it: Raymond Moley and James Warburg. Both of them said Roosevelt had an erratic understanding of economics—which, if you read their diaries carefully, seems to mean that when he agreed with them, he understood it fine, and when he disagreed, he failed to understand. And the earliest historians—Richard Hofstadter in 1948, Arthur Schlesinger in 1957—repeated what these early sources said—that Roosevelt was inconsistent and unreliable on economics, and particularly currency. Historians subsequently have largely relied on Schlesinger and Hofstadter, even though many more sources have become available in the decades since.

But if you look at contemporary sources—even, let’s say, historians and political scientists writing actually during Roosevelt’s presidency—they observed a striking consistency in his statements and actions on monetary policy. And this is what I saw borne out in the primary sources as well: Roosevelt meant from the beginning to end the gold standard, turn the dollar into a managed currency, and in turn create a world system of interdependent, managed currencies, to end the Depression and prove the free world constituted a viable alternative to fascism. And that’s ultimately what he did. Of course none of us is a mind-reader and it’s very hard to establish intent, especially when you’re dealing with someone as cagy as Franklin Roosevelt, but if he says he’s going to do something, and then step by step he does it, that’s about as good a case as you’re going to get, I think.

Q: All right, that accounts for FDR; can you tell us a little bit about what Keynes is doing in the subtitle—and on the cover? Generally if we know anything about the New Deal, it’s that it wasn’t really Keynesian, until maybe 1938 or so, right?

Right, if by “Keynesian” you mean shaped by the idea of fiscal stimulus—it’s true that as much as the New Deal spent on roads, dams, and bridges—as many people as were employed in public works—the arithmetic of fiscal stimulus is such that the US government should have spent more to achieve recovery.

But that’s a poor definition of “Keynesian,” I think, because Keynes spent as much or indeed more of his time thinking about monetary policy, and again, I think we’ve unfortunately neglected not only the monetary policy of the New Deal, but missed the extent to which it was Keynesian. The monetary measures Roosevelt took—to devalue the dollar, to create an international system of managed currencies, and specifically to establish the United Nations monetary and financial institutions (the Bretton Woods system)—Roosevelt did along explicitly Keynesian lines, and sometimes with Keynes’s advice.

Q: But didn’t Keynes compare Roosevelt’s dollar devaluation policy to “the gold standard on the booze”?

Yes, and this is another area in which history has been poorly served by an uncareful reading of sources; it’s tempting to quote Keynes’s quips—and it’s a temptation I’ve succumbed at times—but you have to read them in context of what else he says. Just because Keynes mocked some of Roosevelt’s methods, doesn’t mean he didn’t share his goals. Keynes also said of the dollar devaluation policy that it “means real progress,” that he admired Roosevelt for adopting “a middle course between old-fashioned orthodoxy and the extreme inflationists,” and that it was not only “likely to succeed in putting the United States on the road to recovery” but also to provide the basis for an international system in which nations committed to “provisional parities from which the parties to the conference would agree not to depart except for substantial reasons arising out of their balance of trade or the exigencies of domestic price policy.” And that’s in January, 1934—at which time, if you read that statement, it’s clear that Keynes can see the outlines of what would become Bretton Woods in Roosevelt’s earliest monetary policy.

It seems to me there’s a very interesting set of interactions between Roosevelt, the policymaker intrigued by economic ideas, and Keynes, the economist who can’t resist the desire to wield political influence. Interesting interactions, and salutary ones, I would say, given the circumstances of their successful fight against fascism.

Q: OK, could you say a little bit about how the dollar served as a weapon in the war on fascism?

Sure. When Roosevelt devalued the dollar, over some months ending in January 1934, he made the dollar worth somewhat less in gold than it had been before, going from about $20.67 to an ounce to $35 to an ounce (only for the purposes of international accounting, not for domestic circulation). That meant the gold in US vaults was worth a bit more in dollars—the US had turned a paper profit owing to the devaluation. That profit went into a special fund to be used largely at the discretion of the Secretary of the Treasury, who was then Henry Morgenthau, Jr. Starting in 1935 and over the course of the rest of the decade, even while Congress was passing neutrality legislation to stop the US from providing aid to belligerents, the administration was nevertheless able to use this currency fund for loans—to France, to China—to try to create an alliance against fascism.

That monetary alliance of the 1930s shaded into the lend-lease system during the war, which was again an international system of accounts that operated without gold as its basis, instead relying on, basically, a sophisticated version of barter. Roosevelt used both the monetary stabilization policies of the 1930s and the lend-lease system of the early 1940s as a way of getting into the Bretton Woods system for the peace.

So in its policies to prepare for war, as in its policies for recovery from the Depression, the Roosevelt administration made good use of monetary policy when politics denied it the use of fiscal policy.

Q: Did the Roosevelt monetary policies fail in any respect at all, in your view?

Yes, off the top of my head, I would say in two cases: the attempt to gain full control over the dollar in 1937-38 contributed to the recession of that year, though it taught the administration some important lessons, and also, maybe more importantly, in 1945 the administration failed to get the Soviets to join Bretton Woods.

Q: That’s right, you cover the involvement of Harry Dexter White in Roosevelt’s policy—

—which I think was not as great as has traditionally been said; White joined the administration after its monetary course had already been set, and mainly contributed to the Roosevelt administration by agreeing with and providing statistical arguments for policies already determined by his superiors. But let’s save something for the book.