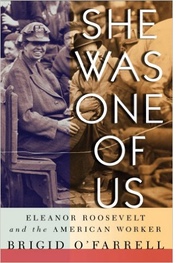

Alas, Eleanor Roosevelt Remains All-Too Relevant to Our Politics

The debate about whose face should grace the $10 bill, provides an excellent opportunity to consider the issue of worker voice. One woman under consideration for the monetary honor has a long record of activism on behalf of working women and men. Eleanor Roosevelt spent the better part of her long and varied career advocating for the American worker and she practiced what she preached. She was a member of The Newspaper Guild, AFL-CIO, for over 25 years. Her words and actions provide historical grounding for the recent White House Summit on Worker Voice.

The

bad news at the summit was that ER is still so relevant. Many of the

issues discussed were ones she worked on more than 50 years ago.

Sitting in the East Room she would learn that American workers are

still being fired for organizing, that right-to-work laws are now on

the books in twenty-five states, women and people of color remain

concentrated in low-wage jobs, and paid family leave, commonplace in

most of the world, is still a mirage in the U.S. Worker stories are

told in a new report,

Stronger Together: How Unions Help

Strengthen Families and the Nation, released

by House Democrats who participated in the summit.

The

bad news at the summit was that ER is still so relevant. Many of the

issues discussed were ones she worked on more than 50 years ago.

Sitting in the East Room she would learn that American workers are

still being fired for organizing, that right-to-work laws are now on

the books in twenty-five states, women and people of color remain

concentrated in low-wage jobs, and paid family leave, commonplace in

most of the world, is still a mirage in the U.S. Worker stories are

told in a new report,

Stronger Together: How Unions Help

Strengthen Families and the Nation, released

by House Democrats who participated in the summit.

Eleanor Roosevelt told delegates to the United Nations that “unions were a fundamental element of democracy.” She believed that the best way to protect workers’ rights was through unionization and legislation; both required strong civic activism. The advantages of unions for workers, communities, and the economy under New Deal legislation became a reality in her lifetime. In the 1950s over one in three workers belonged to a union and the economy was booming; pay, productivity, and profits rose together.

“The middle class was built on the union label,” President Barack Obama told the summit attendees. “When folks attack unions, they’re attacking the middle class…cops, firefighters, teachers, nurses, service workers, public servants, auto workers, plumbers…we should be making it easier, not harder, for folks to join a union.”

Yet a study by the Roosevelt Institute, Blueprint to Empower Workers for Shared Prosperity, released the day of the summit, reports that only 11 percent of today’s workers belong to a union; barely 7 percent of those in the private sector. Many Millennials, whether in Silicon Valley or the Mississippi Delta, don’t know a union member, or are not aware that the teachers and airplane pilots they do know are union members. They are even less cognizant of the impact of collective bargaining in the working world. Technology, globalization, and a growing anti-union culture play complicated roles.

The good news from the summit is that ER’s strategies for increasing worker voice are being adapted for the 21st century. That effort starts with new technology. Few Roosevelt scholars doubt that if ER were alive today she would tweet, blog, maintain a Facebook page, and monitor an Instagram account. She loved new technology and saw its potential. At the summit, the new on-demand economy was showcased by responsible companies such as TaskRabbit and digital organizing tools like Coworker.org whose cofounder Michelle Miller hosted the Town Hall Meeting with the President. Everyone was encouraged to start the conversation, “#StartThe Convo.””

But the sea change in our economy brought about by new technology is also part of the challenge. In her last book, Tomorrow is Now, ER wrote about an economic and a cultural revolution in this country. She highlighted the need for new economic thinking; for education and science to address the challenges of technology and automation. She praised new machinery, but called for “concrete planning for the well-being of human beings who will, slowly but inexorably, be displaced by much of this new machinery.” If jobs are eliminated, and driverless cars are in our future, then we need innovative planning now.

Bringing stakeholders together to start a conversation about the future was a key component of ER’s strategy. She wrote in her My Day column about companies and organizations that were progressive models. She invited workers, union leaders, managers, and policy makers to the White House to stimulate new ideas. The summit panel moderated by Secretary of Labor Tom Perez offers a current example: a worker trying to organize an auto plant in Mississippi, an executive from a premier health organization that successfully negotiates a labor management system with 28 unions, a high school teacher who models collaborative problem solving to improve classroom experiences, the executive of a grocery store chain that rallied entire communities to counter a negative turn in their corporate culture, a senator who successfully led an effort to defeat a right-to-work law in his state.

Government action was another critical strategy. ER opposed the Taft-Hartley Act of 1947, curtailing the National Labor Relations Act, calling it a “bad bill” that struck “at the fundamental rights and protection of labor.” She also recognized that the New Deal legislation excluded many workers and needed to be expanded. Now, decades later, it is time for serious labor law reform such as the recently introduced Workplace Action for a Growing Economy (WAGE) Act to expand coverage of labor law protections and strengthen enforcement. At the summit labor law alternatives were discussed as part of what the Roosevelt Institute report called “reimagining the rules of the workplace,” making it more “inclusive, dignified, and just.”

Encouraging citizen activism was critical to all of these efforts. While Eleanor Roosevelt believed strongly in the power of collective action she recognized that the action needed to be solidly rooted in individual responsibility and personal courage. In You Learn By Living she wrote “You must do the thing you think you cannot do.” And one Town Hall participant echoed “you cannot be afraid.” The White House Summit showed how Individual workers are challenging companies in new ways, business owners are taking risks on new approaches, policy makers are innovating, and union and community leaders are finding new ways to collaborate and organize.

Above all, Eleanor Roosevelt was a political realist. She understood that the battle for economic justice was never ending and that “the most powerful weapon we have at our command today is public opinion.” Labor’s challenge in the twenty-first century is the same as it was in ER’s time; telling labor’s story in a compelling, comprehensive way so that every American understands what is at stake. Putting Eleanor Roosevelt on the $10 bill would be one way to acknowledge her belief that workers’ voices must be heard and “#StartTheConvo.”