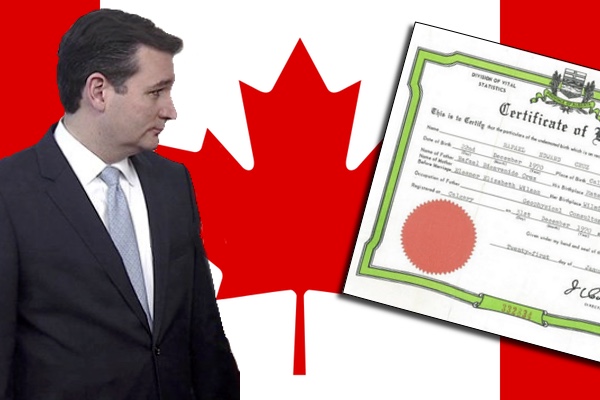

Ted Cruz: Is He or Isn’t He a Natural Born Citizen?

Related Link: Natural-Born Presidents

One month ago, Article II, Section 1, Clause 5 was the exclusive province of die-hard Obama-hating “birthers.” Now, we all want to know: Is Ted Cruz, born to an American mother on Canadian soil, a “natural born citizen,” as he must be to become president?

In legal terms, there are two ways to interpret “natural born citizen”: jus soli (“right of the soil”) and jus sanguinis (“right of blood”). Place or parentage, those are the options. Which method is enshrined in the United States Constitution?

Let’s ask originalists, people like Ted Cruz.

The records of the Federal Convention of 1787—the starting point for any originalist inquiry—are replete with debates on almost every provision, but, sadly, not this one. In fact, the framers had been deliberating for almost two months before they raised the question of requirements for federal office. On July 26 George Mason noted the lapse. Upon his urging, the convention instructed the newly formed Committee of Detail to prepare “a clause or clauses, requiring certain qualifications of landed property and citizenship in the United States for the Executive, the Judiciary, and the Members of both branches of the Legislature of the United States.”

The committee did not fulfill its task. It required three years of citizenship for representatives and four years for senators, but said nothing about the president or justices. This apparent oversight is easily explained. At that point in the deliberations, both the president and members of the judiciary were to be appointees of Congress. Their offices were derivative, not original, so it was left to Congress to determine their qualifications.

Four weeks later, a committee suggested that the president should be an “inhabitant” of the United States for twenty-one years, but no action was taken on this proposal.

That is where matters stood on September 4, when an eleven-member committee, composed of one delegate from each state, issued its report. This committee was instructed to address matters “that have not been acted on,” but it went far beyond its mission. Prior to that moment, after extensive deliberations, the convention had determined that the president would be elected by a joint session of Congress, serve for seven years, and be ineligible for reelection. Treaty and appointive powers were assigned to the Senate. Reversing these decisions, the Committee on Remaining Matters (as it is now called) recommended that the president be chosen by special electors (known now as the Electoral College), serve a four-year term, be eligible for reelection indefinitely, and assume treaty and appointive powers, subject only to the “advice and consent” of the Senate. It also created a new office of vice president, whose only official job was to preside over the Senate, and determined that the president must be a “natural born citizen.”

The committee’s report marked the first time “natural born citizen” came before the body, and not a word about that provision was said on the floor. Larger issues were at stake, and even these were scarcely debated. Having labored for more than three months, delegates yearned to be done with it all. For want of will to continue, the framers enshrined the bulk the committee’s report in the United States Constitution. Only the method of run-off elections in the House, should presidential electors fail to achieve a majority vote, was altered. The “natural born citizen” requirement, like most of the committee’s more significant revisions, was rushed through. The distinction between jus soli and jus sanguinis was, literally, about the last thing on the framers’ minds as they constructed a new framework for the nation.

“Natural born” is not the only problem. How about “citizen”?

Under the Articles of Confederation, still in force during the summer of 1787, Congress engaged only with states, and states with citizens. A “citizen of the United States” was a citizen of one of the confederated states. The framers were literally creating national citizenship by forming a government which passed laws binding on citizens, and to which citizens sent their representatives.

National citizenship piggybacked on state citizenship. According to Article IV, Section 2, Clause 1, “The Citizens of each State shall be entitled to all the Rights and Privileges of the Several States.” (The Articles of Confederation had this same provision.) Rather than establish federal franchise requirements, the framers determined that anybody entitled to vote in a state’s “most numerous branch” of its legislature would be entitled to vote for federal representatives. Beyond that, Congress would figure out who could become a citizen. The fourth power granted to Congress, preceded only by powers to tax, borrow money, and regulate commerce, was “To establish an uniform Rule of Naturalization.” American citizenship was a work-in-progress.

When the First Federal Congress created this “uniform Rule of Naturalization,” it weighed in on the side of jus sanguinis, “right of blood.” According to the Naturalization Act of 1790, “The children of citizens of the United States, that may be born beyond sea, or out of the limits of the United States, shall be considered as natural born citizens.” There was a nod to place, however: “Provided, That the right of citizenship shall not descend to persons whose fathers have never been resident in the United States.”

This provides a hint about the framers’ views. One third of those who participated in the Federal Convention of 1787 were in the First Federal Congress, ten senators and eight representatives. These included eight of the eleven members of the Committee on Remaining Matters, which had introduced the “natural born citizen” requirement at the Convention. Several of these men likely assented to the Naturalization Act, including its preference for parentage over place.

But it’s only a hint. We do not know how each of these framers-turned-legislators felt about this one provision of a sweeping measure. We do know, however, that James Madison, on May 22, 1789, in the House of Representatives, voiced a clear preference for place over parentage: “It is an established maxim that birth is a criterion of allegiance. Birth however derives its force sometimes from place and sometimes from parentage, but in general place is the most certain criterion; it is what applies in the United States.” For Madison, at least in this passage, place prevailed absolutely, with no nod to parentage. And Madison had also been a member of the Committee on Remaining Matters.

There are more complications. In 1795, the earlier Naturalization Act was repealed, and the one that took its place made a significant change in wording: “The children of citizens of the United States, born out of the limits and jurisdiction of the United States, shall be considered as citizens of the United States: Provided, That the right of citizenship shall not descend to persons, whose fathers have never been resident in the United States.” Citizens, but nothing about natural born. Was this to correct what legislators, still of the Founding generation, perceived as an error in the first act? Regardless of intent, the revised act does not state unequivocally that a person of American descent, not born on American soil, meets the eligibility requirement for the presidency.

And one more concern: “Right of blood,” in those days, meant the father’s blood; even in the Naturalization Act’s nod to residency, it was all about fathers, not mothers. Of course that has changed, but not by Constitutional amendment. If we look for original intent to settle the issue, this gender bias cannot be ignored.

Although the search for original intent cannot yield a definitive answer, what about the original meaning of “natural born citizen”? How did people at that time, and in particular those who ratified the Constitution in 1788, construe this term?

Originalists who scour the voluminous sources from the ratification debates will not have their efforts rewarded. There is a scattering of evidence that reveals the obvious motive behind the “natural born citizen” requirement—no European prince should be imported to lead our nation—but none that elucidates a common understanding of how that was to be defined, by place or parentage. Even Hamilton’s eleven Federalist essays on the presidency are silent on this matter. Insuring that the president would not be a foreigner, by whatever standard, was among the Constitution’s least contentious provisions. Nobody thought it was a bad idea, and without argument, there was little to discuss.

Where else to turn? Paul Clement and Neil Katyal, Solicitors-General in the George W. Bush and Obama administrations respectively, wrote a brief commentary in the Harvard Law Review that has received much attention in the past few days. On the basis of the Naturalization Act of 1790 and Eighteenth Century British statutes, and upon the authority of William Blackstone, whose Commentaries were read widely and cited often by American jurists of the Founding Era, they side with parentage over place and proclaim the case closed.

But another legal scholar, Mary Brigid McManamon, in a more extensive piece published in the Catholic University Law Review, counters that argument. “Natural born Citizen,” she observes, is a phrase “derived from English common law, and the Supreme Court requires examination of that law to ascertain the phrase’s definition.” After citing provisions of English common law, “statements by early American jurists,” and passages she selects from Blackstone, she declares, with equal certainty, that “in the eyes of the Framers, a presidential candidate must be born in the United States.”

How can we conclude, on the basis of scant contemporaneous evidence and conflicting claims by modern scholars, whether the framers would allow the child of an American mother, born on foreign soil, to become president of the United States? Inquiry into the original intent of the framers does not settle this issue.

Nor is original meaning much help. How can we be sure that the people who ratified the Constitution would affirm— or deny—Ted Cruz’s eligibility? How did all those folks in thirteen states define “natural born citizen,” by place or by blood?

Here is my “originalist” conjecture. “Right of blood” versus “right of place” was a non-issue for the people of those times—even for the ever-fastidious framers, who argued at great length about so much else. The Founding Generation took no notice and didn’t really care; they just knew that no foreigner should be president. If forced to declare, they would probably say there had to be some connection by both place and blood, just to be safe. A French couple, while traveling, has a child on American soil? Not good enough. An American couple has a child in England, and the family remains there? We need our president to be more American than that, define it as you will. If the framers had more time, and if they deemed it as significant as we do right now, they might have figured something out, but they didn’t. Instead, by their failure to act, they left it to Congress to conjure a definition.

But this is only a conjecture, and we can’t build a case on that. Try as we might, originalism in any form fails us here. But if we use the originalist standard only at our ease and pleasure, can it count as a “standard”?

How ironic that Ted Cruz, who has promised to appoint only originalist justices, has become the poster-child—or more precisely, poster-infant—for originalism’s deficiency.