A Close Observer of Congress Reports that Senators of Both Parties Still Cooperate

Related Link National History Center briefing on partisanship

Barack Obama has lamented that political polarization has grown worse during his presidency. Not surprisingly, an increasingly polarized electorate has deepened the divide in Congress. Campaigning by promising not to compromise, senators and representatives have gained credit back home for delaying or blocking legislative action. They have promised to repeal rather than create programs, to reduce regulations, and cut spending, taxes, and deficits. Structural differences between the Senate and the House, and ideological animosity between the Congress and the presidency, have further hindered legislative productivity.

All this is far cry from the legislative situation Robert Axelrod described in his classic study, The Evolution of Cooperation (1984), an exploration of the conditions under which cooperation can emerge in “a world of egoists without central authority.” Using the Senate as a case study, Axelrod argued that while senators naturally have an interest in appearing effective to their constituents, at the expense of conflicting with their colleagues who are playing to their own constituencies, there were also many opportunities for “mutually rewarding actions,” which had led to “an elaborate set of norms, or folkways, in the Senate.” In particular, he cited was the norm of reciprocity, “a folkway which involves helping out a colleague and getting repaid in kind.”

This notion of cooperation and reciprocity no longer registers with C-SPAN audiences who have grown accustomed to seeing minority party senators filibustering and voting down cloture motions, and majority leaders using such parliamentary devices as “filling the amendment tree” to prevent the minority from introducing amendments. In an age of polarized politics, Axelrod’s image of a cooperative Senate seems archaic.

Fortunately, evidence suggests that cooperation is not entirely a thing of the past. Much committee business continues to be done on a bipartisan basis because like-minded senators are drawn to the same committees out of concerns over similar issues, from agriculture to armed services, highways to homeland security. In the Senate chamber, a surprising amount of business, both small and large, is done with unanimous consent, meaning without any dissent. Bipartisan compromises can still be reached, for the same impulses and tactics that Axelrod described, although perhaps more covertly than in the past.

Skeptics seeking verification should read Lion of the Senate: When Ted Kennedy Rallied the Democrats in a GOP Congress (Simon & Schuster, 2015) by two of Kennedy’s key staff members, Nick Littlefield and David Nexon. Drawn from Littlefield’s notes of strategy meetings, they document how skillfully the senator managed to influence policy in the hyper-partisan era that followed the Contract with American political sweep of 1994. Arguing that all legislation is bipartisan, the liberal Kennedy reached out to his conservative counterparts, finding in each case the sole issue they could agree upon. He coaxed, cajoled, pleaded and thundered to attract further support and create common ground. The book describes Kennedy’s “inside game” and “outside game,” building relationships with legislators in both parties to form alliances around bills, and then building grassroots support around the country so that members would hear from their constituents.

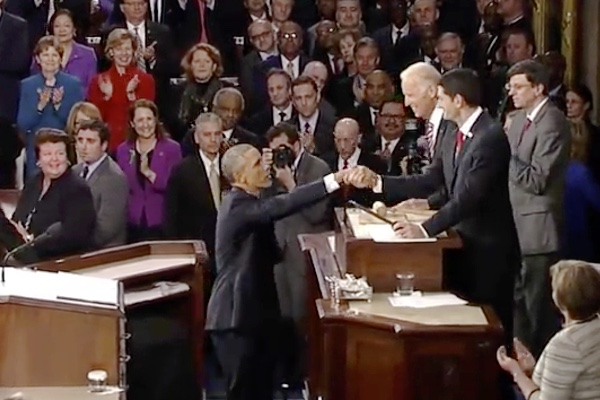

Legislative success still depends in part on knowing what colleagues want, the type of horse trading that Axelrod identified as fundamental to compromise. Littlefield and Nexon cite a favorite example that occurred one night when North Carolina Senator Jesse Helms was using “holds” (signals that he would object to unanimous consent agreements) to block a series of health care bills Kennedy was promoting, with the clock about to run out before adjournment. Finding Helms uninterested in cooperating with him, Kennedy turned to Senator Joe Biden, then chairman of the Judiciary Committee. Biden held an ace up his sleeve: a judicial nominee from North Carolina that Helms strongly backed but that Biden had buttoned-holed for just such a purpose. Biden took Helms to a back corner of the Senate Chamber, out of C-SPAN camera range. He returned with a checklist of bills, noted on the back of an envelope, on which Helms had agreed to lift his holds. The Senate passed Kennedy’s bills that night, and Helms got his judge. Some things still work.