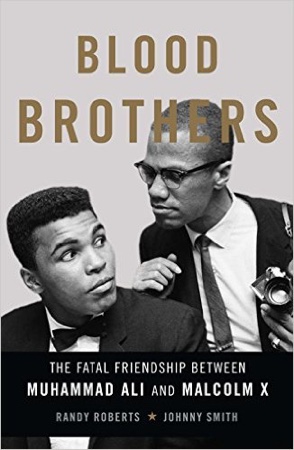

Who Was the Real Muhammad Ali?

In Blood Brothers, we argue that the real Muhammad Ali can only be understood when his many masks are uncovered. Why did Ali wear different masks? Why did he live a double life?

From 1960 to 1965, the half-decade that framed his relationship with Malcolm X, the boxer appeared convincingly as four different personalities, packaged and expressed at different times for different audiences. He first emerged on the world stage as Cassius Marcellus Clay Jr. of the 1960 Rome Olympics—wide-eyed, talkative, enthusiastic, and likable, a defender of the glacial progress being made in American race relations. After turning professional toward the end of 1960, he became the Louisville Lip—boasting loudly, spouting poetry, belittling opponents, and advertising himself. During this period, Clay knew that if his relationship with the Nation of Islam became public knowledge, it would effectively end his career. Therefore, he lived a double-life—a life of deception—presenting the face of the courteous, submissive, and patriotic “Good Negro” in public but a radically different one in private. When Clay secretly attended Black Muslim rallies, he revealed another side of himself: angry, resentful, and defiant of white authority.

As the civil rights movement escalated from 1962 to early 1964, he evolved into Cassius X—the loyal follower of Elijah Muhammad, the Supreme Minister of the Nation of Islam. As Cassius X, a name he adopted only for a brief time, he imitated Malcolm X, appearing angry and outraged by racial injustice. Finally, after winning the heavyweight title in February 1964, he became Muhammad Ali—renamed by Elijah, pried apart from Malcolm, and the new front man for the Nation of Islam. As in his other personas, he inhabited the role of Muhammad Ali, often wearing the somber, stone-faced mask of Elijah’s paramilitary followers.

Cassius Marcellus Clay Jr., the Louisville Lip, Cassius X, and Muhammad Ali—the boxer played all these roles, wearing the different masks as the occasion dictated. He was all of these characters, and sometimes more than one at the same moment.

Why was Malcolm X uninterested in sports, but drawn to Cassius Clay?

Like other members of the Nation of Islam, Malcolm believed that professional sports—and especially boxing—were controlled by white men and exploited black men. But gradually Malcolm recognized that Cassius possessed the kind of far-reaching cultural power that could unify black people. Like Malcolm, Clay was absolutely self-assured, proud, and defiant. He carried himself with boundless confidence, boldly professing his greatness the way that Malcolm fearlessly denounced white men. Studying Clay’s interactions with reporters, the way he spellbound audiences with his performances, Malcolm realized that he could become something more than an athlete. As their relationship developed, Malcolm envisioned Cassius Clay as the spokesman of a Black Nationalist movement, one built around celebrity and politics.

How did Malcolm exploit his friendship with Cassius Clay?

After Elijah Muhammad suspended Malcolm X from the Nation of Islam, effectively exiling the minister, Malcolm began considering his future. If Elijah permanently banished him from the Nation, Malcolm calculated, he needed to consider how he could take Clay with him. But if he were ever going to return to the Nation, he would also have to think about how his friendship with Clay might lead him back into Elijah’s arms.

During his suspension, Malcolm decided what Clay needed was a dose of political reality. He wanted Cassius to see the dark side of the Nation and its leader. Malcolm fully understood that Elijah had ordered him not to talk with reporters and had commanded other members of the Nation not to associate with the defrocked minister—a directive that certainly applied to Cassius Clay. Yet instead of moving a step behind Elijah, reacting to the Supreme Minister’s edicts, Malcolm chose to take the lead and compel him to follow. If Malcolm went to Miami, where Clay was training on the eve of his title fight with Sonny Liston, and he flaunted his relationship with Cassius, he would challenge Elijah to either pull Malcolm back into the fold or punish Cassius. Either way, Malcolm thought, it would strengthen his relationship with Cassius.

On the day of the Clay-Liston title match, February 25, 1964, Malcolm phoned the Nation’s headquarters in Chicago. Whether he talked directly with Elijah or one of the Prophet’s leading aides is unclear from the FBI informant’s report. Whomever Malcolm talked to—Elijah or one of his lieutenants—Malcolm repeated his absolute belief that Clay would defeat Liston, potentially making the boxer the Nation’s most important convert and marketable asset. He also promised to deliver Clay to Chicago for the Nation’s annual Saviour’s Day Convention. All Malcolm wanted in return was complete reinstatement. His offer was rejected. Elijah Muhammad had other plans; he did not need Malcolm to secure Clay’s loyalty.

In Blood Brothers we maintain that once Muhammad Ali severed ties with Malcolm X, the minister’s life was more vulnerable. How did Malcolm’s friendship with Ali become a matter of life and death?

Blood Brothers reveals how Cassius Clay became a pawn in the power struggle between the leader of the Nation of Islam, Elijah Muhammad, and Malcolm X. When Malcolm’s life was in danger, when Elijah Muhammad threatened to cast him outside the Nation, Cassius Clay became the central figure in his world. The moment Malcolm realized he might be murdered, he tethered his future—his very survival—to the life of a boxer who most people figured would never win the heavyweight championship. Malcolm had no doubt that someone inside the Nation wanted him dead. He also knew that none of Elijah Muhammad’s disciples would risk Clay’s life. As long as they were together, Malcolm figured, he was safe. Cassius was the perfect shield. However, only ten days after they celebrated the boxer’s championship victory over Sonny Liston, Cassius stopped taking Malcolm’s phone calls. Submitting to Elijah, the champ accepted a new name and the Supreme Minister’s edict that all Muslims cease contact with Malcolm. Once Muhammad Ali sided with Elijah, and effectively replaced Malcolm as the Nation’s new spokesman, Malcolm knew that he could no longer hide behind him. At that moment, he recognized that losing Ali’s cover might cost him his life.

What were young Cassius Clay’s views about the civil rights movement? Why did he reject Martin Luther King’s approach to integration?

As a young boy, Cassius Clay heard his father remind him countless times that he should avoid white people. Whites, Clay, Sr. warned, could not be trusted. The violent stories young Cassius heard about lynchings at the hands of whites scared him. Repeatedly his father exhorted: don’t leave our neighborhood. Don’t go into white people’s stores. Don’t contradict a white man. Don’t look at white women. Don’t disobey policemen. And most importantly, don’t get arrested. These warnings convinced Clay that integration would never work. Black people, he thought, simply could not trust whites. History proved it.

Clay wasn’t interested in joining civil rights demonstrations. He may have been a boxer, but he disliked confrontations and avoided violence outside the ring. For Cassius, the Black Muslims belief in racial separatism made sense. The Nation of Islam offered him a sanctuary from the violent world that surrounded him. “I believe it’s human nature to be with your own kind,” he declared in 1963. “I know what restrooms to use, where to eat, and what to say. I don’t want people who don’t want me . . . I don’t like people who cause trouble. I’m not going out there to rile up a lot of people.”

Listening to Malcolm X, Cassius was convinced that Martin Luther King’s philosophy of nonviolence failed to advance the civil rights struggle. “I’m a fighter,” he proclaimed. “I believe in the eye-for-an-eye business. I’m no cheek-turner. The NAACP can say ‘turn the other cheek,’ but the NAACP is ignorant.”

What made Muhammad Ali the most controversial athlete of the 1960s? How did he change the role of the black athlete in America?

Ali’s involvement with Malcolm X and the Nation of Islam—a sect most Americans considered a hate cult—made him the most controversial athlete in the country. Writers compared his racial views to the Ku Klux Klan, the White Citizens’ Council, and the Dixiecrats. Many Americans feared that Ali would use his boxing title to influence young, angry black men to join the Nation. Ali, Jimmy Cannon charged, threatened to turn boxing “into an instrument of mass hate.” Even Martin Luther King denounced Ali when he announced his membership in the Nation of Islam. “When Cassius Clay joined the Nation of Islam he became the champion of racial segregation—and that is what we are fighting.”

How did Ali react to Malcolm’s murder? And what were the consequences of their fallout?

After Ali broke from Malcolm, the boxer wore a new mask, playing the part of the serious, vindictive Black Muslim. When Ali cut Malcolm out of his life he revealed a new side of himself that the public had not yet seen: an angrier, crueler side that would develop more and more in the coming years. Whenever there were other Black Muslims around, he assumed this role, conforming to the expectations of Elijah Muhammad and the Nation’s officials. Ali predicted Malcolm’s demise. “Malcolm X and anybody else who attacks or talks about attacking Elijah Muhammad will die.”

After Malcolm’s murder, reporters hounded Ali, probing for answers about the Nation’s involvement in the assassination. Ali insisted that the Black Muslims were innocent. When New York Times columnist Robert Lipsyte asked the champ about the murder, he coldly said Malcolm “got what he deserved.”

In the years after Malcolm’s murder, Ali lived in fear. Controlled by Elijah Muhammad for more than a decade, Ali felt trapped by the Nation of Islam. He worried about what would happen to him if he broke from the Nation. “I can’t leave the Muslims,” Ali said, his voice foreboding. “They’d shoot me too.”

More than forty years after Malcolm died, Ali regretted the way their relationship ended. “I wish I’d been able to tell Malcolm I was sorry, that he was right about so many things,” he said. “Malcolm X was a great thinker and even greater friend. I might never have become a Muslim if it hadn’t been for Malcolm. If I could go back and do it over again, I would never have turned my back on him.”