The One Way Presidential Candidates Could Honor George Washington Is the One Thing They Won’t Do

Well into the 2016 presidential sweepstakes, the long ordeal of a seemingly endless campaign awaits the American people to test their indulgence as well as their patience. Swamped by position papers that carry about as much weight as convention platforms and speeches full of political boilerplate tested and tweaked by armies of consultants, Americans also hear the constant appeals for money, now the mother’s milk of politics. It is enough to make the thinking citizen nostalgic for the time when people stood for office rather than ran after it and at least gave the appearance of being summoned to service rather than scrambling for the ostensible privilege of doing good that usually winds up with them doing very well.

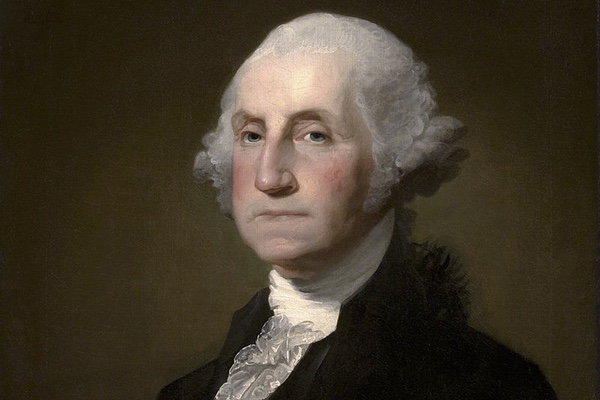

Nostalgia beckons

when you consider that George Washington did not run for office. He

did not want to be president in the first place, but he also thought

it unseemly to treat the post as a prize. His reticence became the

traditional attitude, at least in appearance, of those being

considered for the presidency for a century after his example. True,

the ideal was honored more often in the breach, since “being

considered” after Washington in reality meant “actively seeking,”

but the republic could take comfort in the tribute that those barely

veiled vices paid to virtue.

Nostalgia beckons

when you consider that George Washington did not run for office. He

did not want to be president in the first place, but he also thought

it unseemly to treat the post as a prize. His reticence became the

traditional attitude, at least in appearance, of those being

considered for the presidency for a century after his example. True,

the ideal was honored more often in the breach, since “being

considered” after Washington in reality meant “actively seeking,”

but the republic could take comfort in the tribute that those barely

veiled vices paid to virtue.

Washington’s example set a high bar. Even if his reluctance had proceeded from superficial motives (it didn’t), any sensible man would have balked at the challenge posed by establishing a new government. Everything about it under the Constitution would be starting from scratch, and the first president’s every move would set precedents and establish procedures that would serve as the foundation of the executive branch. If not nearly right in everything, all might be completely wrong forever after.

These concerns about form were matched by material difficulties. The new government was inheriting enormous problems from the one it was replacing, troubles that put in perspective claims of the current political class about its unprecedented predicaments. In 1788 the treasury was empty (rather like now), but those Americans had at best a slender thread of credit that was quite fragile and bordering on bad. Hostile neighbors prowled America’s borders, and France, its only ally of consequence, was beginning a revolution that would devolve into political turbulence and social instability. Domestically, unrest had boiled over in Massachusetts where disgruntled taxpayers had taken up muskets to give force to their complaints. And the Constitution itself, the foundation of the government yet to be built, inspired suspicion in a considerable number of citizens unsure of its intentions.

Washington had doubts about his physical stamina for the task. His fatigue from the eight years of fighting the British in the Revolutionary War was still palpable, and age was taking its toll in any case. His memory was occasionally uncertain, his vision was dim, and he was going deaf. Meanwhile, his life after the war had settled into rhythms and routines he found congenial and comforting. He rose early, filled his days inspecting his farms, and returned to a house always filled with admiring guests and sparkling conversation. His reputation was at its zenith, and with nothing left to prove he had very much to lose in risking his standing with his countrymen and the world by taking on a thankless job with appalling responsibilities, something hardly suited to a taciturn man accustomed to military settings that obliged automatic obedience.

These were Washington’s sentiments when his friends began trying to dragoon him into the job. He received a letter from Alexander Hamilton in September 1788 pointing out that “a Citizen of so much consequence” had no choice but to serve. Other men Washington respected, such as fellow Virginian James Madison and Gouverneur Morris, soon joined Hamilton. Madison visited Mount Vernon twice in late 1788, and Morris finally wrote in some exasperation, “You must be President. No other man can fill that Office.”

Morris wasn’t engaging in flattery to cajole but was stating an obvious fact. Article II of the Constitution had been drafted with Washington in mind. He was the reason the Constitutional Convention could justify the president’s powers, in part because he had proven himself a prudent man when given power. He had refused to exercise it at the end of the war when he had been exceedingly popular and at the head of an army that would have given him an American crown, had he wanted it. Instead, he had resigned his commission and returned home.

In the end Washington grudgingly gave in. Nevertheless, he did not formally announce his intention to serve even after the Electoral College unanimously named him president. The clearest sign that he would accept the office was his taking out a personal loan to pay for his travel to the capital in New York City and cover his living expenses when there. The lessons he provided in this crucial episode were thus framed in a refreshing humility.

For there was something else about Washington’s soul-searching during those months when his country called and he remained reticent. He and his colleagues in the new government were firm in their belief that power is not the same as authority. Power can corrupt and usually does, as was apparent to these men a century before Lord Acton gave us his famous aphorism about absolute power corrupting absolutely, with the additional observation that great men were almost always bad people. Washington would have recoiled from the latter sentiment as well as the charge. Authority, in his view, derived from the people’s conditional consent broadly achieved, freely given, but always with the caveat that consent can only last as long as those wielding authority do so virtuously.

Everyone aspiring to the office that George Washington established might best advance their quests by remembering his examples of humility and virtue. During the ratification debates on the Constitution, Hamilton had insisted that “talents for low intrigue, and the little arts of popularity” would win neither public acclaim nor the highest office in the country’s gift. Instead, Hamilton was sure that Americans would insist that the presidency be “filled by characters pre-eminent for ability and virtue.” Hamilton was undoubtedly right about the first time, given the first character everybody had in mind, an exemplar of limited ambition and humble virtue. At the moment of decision, George Washington did not hold a fundraiser. He took out a loan.