Why Bernie’s Right About Glass-Steagall

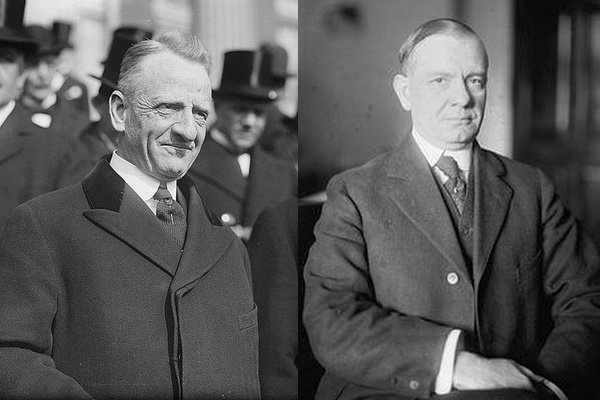

Sen. Carter Glass (D–Va.) and Rep. Henry B. Steagall (D–Ala.-3), the co-sponsors of the Glass–Steagall Act.

Both Hillary Clinton and Bernie Sanders are talking tough about Wall Street reform. But only Bernie Sanders is advocating a reprise of the 1933 Glass-Steagall Act, specifically that section of the Depression-era act that had prohibited commercial banks and investment banks from operating under the same roof. Sanders believes that the repeal of Glass-Steagall in 1999 led to the formation of banks that became “too big to fail,” contributed to the financial crisis in 2008—and will lead to another crisis without corrective legislation.

Most

observers think Sanders is on a quixotic quest and, with Wall

Street’s political power, the chances of any revival of

Glass-Steagall are, like his election to the presidency, slim. Yet

Sanders has a strong argument, one that can be effectively made using

Citigroup, the two-century old bank that, along with other Wall

Street banks, has a history of wreaking havoc on itself and the

economy when it mixes commercial banking with investment banking

Most

observers think Sanders is on a quixotic quest and, with Wall

Street’s political power, the chances of any revival of

Glass-Steagall are, like his election to the presidency, slim. Yet

Sanders has a strong argument, one that can be effectively made using

Citigroup, the two-century old bank that, along with other Wall

Street banks, has a history of wreaking havoc on itself and the

economy when it mixes commercial banking with investment banking

The first instance occurred in the 1920s when Charles “Sunshine” Mitchell became president of what was then National City Bank. The bank was the largest in the U.S. and its securities affiliate, under his aggressive management, had also become the country’s largest investment operation, with sixty-nine sales offices in fifty-eight cities. Much of National City Bank’s growth, however, was at the expense of its growing clientele of unwary investors, who became victims of shoddy securities offerings the bank originated and, most famously, the notorious investment pools the bank sponsored in the Roaring Twenties.

In 1933, long after the 1929 stock market crash and in the depth of the Great Depression, Mitchell was brought before the Senate Banking and Currency Committee to explain how investment pools worked and how National City Bank played a role. First, it turned out, the bank loaned money to a “pool manager” to facilitate the purchase of a selected “story stock” by a small group of initial investors. Then the pool manager planted rumors and bogus news accounts to entice the general public to purchase the stock at ever increasing prices. National City’s investment affiliate further aided the pool manager in its efforts by authorizing the payment of “premium” commissions to tout the targeted stock. When the stock’s price reached some level judged unsustainable by the pool manager, the early investors quietly bailed out, leaving smaller and less informed investors holding the bag. If those chump investors had purchased their stock on margin, they likely owed large sums of money in addition to holding the deflated stock.

And buying stocks on margin was a practice greatly encouraged by National City Bank, a major supplier of “broker loans.” When the Federal Reserve tried to tamp down stock market speculation in 1929 by limiting the amount of margin debt, Mitchell—himself a member of the Fed’s board of governors—instructed National City to go directly counter to the central bank’s wishes by increasing the high volume of broker loans it was already providing. During the Senate hearings on the collapse of the stock market, Senator Carter Glass (the Glass in Glass-Steagall) proclaimed that Mitchell “more than forty others is responsible for the present situation.”

As the hearings were being conducted, the Glass-Steagall Act was already in the works to cleave the securities business from traditional, deposit-backed commercial banking to prevent future abuses. Financial institutions that had largely stayed above the fray and ran respectable businesses felt unjustly victimized by the actions of miscreant banks. J.P. Morgan, Jr. sounded an ominous warning about the likely effect of Glass-Steagall on his bank, stating, “If we should be deprived of the right to receive deposits we should very probably have to disband a large part of our organization, and thus should be less able to enter into in the future that important service in the supply of capital for the development of the country which we have rendered in the past.”

But shortly after Mitchell’s damning testimony before the Senate committee, the Glass Steagall Act sailed through Congress and the strictures of the act applied not only to National City Bank and other misbehaving banks, but to all financial institutions. Yet despite Morgan’s dire protestations, his mighty House of Morgan did just fine after it was split into J.P. Morgan, the commercial bank, and Morgan Stanley, the investment bank—and for the rest of the twentieth century the country enjoyed remarkable economic growth despite a bifurcated financial system made up of relatively small banks and investment firms.

But fast forward sixty or so years, into a more deregulated era, and bankers once again began echoing Morgan’s arguments on the need for large, integrated financial institutions for the U.S. to remain competitive in the global economy. Consequently, the Federal Reserve relaxed many of the provisions meant to enforce Glass-Steagall, and its chairman at the time, Alan Greenspan, stated in a private conversation that he would have no problem in principle approving a merger between a commercial bank and an investment bank—as long as Glass-Steagall was repealed.

The other person in that private conversation was Sandy Weill, who had put together a major financial conglomerate called Travelers Group, made up of some of the leading insurance and investment firms of the day, and who had set his sights on acquiring a large commercial bank. Emboldened by Greenspan’s favorable view, Weill forced the issue in 1998 by negotiating a $70 billion merger of Travelers Group with Citicorp, the commercial bank that was the outgrowth of National City Bank. He then undertook a full-court lobbying effort with members of Congress to repeal Glass-Steagall in order to make the combination legal. Using Morgan’s earlier arguments centered on competitiveness in the world economy, both the House and Senate came on board. President Bill Clinton, who initially withheld his support of the repeal, was reportedly turned around on the issue at the last minute by Weill and eventually signed the Financial Services Modernization Act of 1999—and Glass-Steagall was no more.

The combined operation that became Citigroup was initially managed by co-CEOs—Weill from the Travelers side and John Reed from Citicorp. It would be hard to find two more divergent management styles than theirs. Reed was a traditional commercial banker whose long-term mission was to continue developing Citicorp into the world’s premier global bank. Weill had a very different style. When asked about his philosophy of strategic planning, Weill replied, “I get up in the morning, I read the Wall Street Journal, and I make a strategic plan for the day.” In the inevitable struggle for the top position, Weill beat out Reed—and a new era of rapid growth, further acquisitions, and risk taking took hold at Citigroup.

Weill reluctantly retired in 2003, but his successor, Chuck Prince, was, if anything, more aggressive and risk prone in combining the commercial banking side of the business with the investing side. In 2007, when asked about the bank’s $100 billion leveraged lending program to support private equity deals, he remarked, “When the music stops, in terms of liquidity, things will be complicated. But as long as the music is playing, you’ve got to get up and dance. We’re still dancing.” He likely had the same view about the housing markets at a time when Citigroup was originating large numbers of mortgage loans as a lender and then packaging and selling them in the securities markets as a broker. But the music indeed stopped the next year and to prevent the bank’s collapse—and the national economy with it—the U.S. government wound up backing over $300 billion of Citigroup assets and making a direct injection of $45 billion in its equity account.

With a more watchful regulatory environment and the reforms in place following the passage of the Dodd-Frank Act in 2010, Citigroup and the other Wall Street banks have been behaving much better. But commercial banking and investment banking remain very different cultures and letting them continue to operate under the same management represents a triumph of hope over experience. The next crisis will not likely involve bank financing of investment pools, or making undo amounts of margin finance available to brokers, or making high leverage loans to finance equity investments, or originating, packaging, and selling low-quality mortgage loans. And it may not involve Citigroup. But, absent a new version of Glass-Steagall, there will very likely be something just as calamitous. As the quip attributed to Mark Twain goes, history doesn’t repeat itself, but it rhymes.

Bernie’s probably right on this one. Even Sandy Weill—who once was proud to be referred to on Wall Street as the “Shatterer of Glass-Steagall”—now seems to agree. In a 2012 interview on CNBC he said, “What we should probably do is go and split up investment banking form banking. Have the banks do something that’s not going to risk the taxpayer dollars, that’s not going to be too big to fail.”