Five Things You Didn’t Know About John James Audubon

1. This may not sound important, but it is: Audubon was not born in Louisiana, despite his claims to the contrary.

During his life, Audubon identified Louisiana as his birthplace. It was a complete fabrication, but he did so to conceal his origins, a family secret that could threaten his place in polite society.

In

truth, Audubon was illegitimate, born on April 26, 1785, in the

French colony of Saint- Domingue (now Haiti), to Jean Audubon, a

French sea captain and sugar plantation owner, and his French

mistress, who died six months later. Concerned about a possible slave

revolt on the island, Jean sent the boy to France in 1788, where he

was raised by Jean’s childless wife, Ann. As an illegitimate child,

Audubon would have been unable to take his father’s name or inherit

property. So, in 1794, Jean and Ann formally adopted him.

In

truth, Audubon was illegitimate, born on April 26, 1785, in the

French colony of Saint- Domingue (now Haiti), to Jean Audubon, a

French sea captain and sugar plantation owner, and his French

mistress, who died six months later. Concerned about a possible slave

revolt on the island, Jean sent the boy to France in 1788, where he

was raised by Jean’s childless wife, Ann. As an illegitimate child,

Audubon would have been unable to take his father’s name or inherit

property. So, in 1794, Jean and Ann formally adopted him.

However, the stigma of illegitimacy and the fear that it would be revealed hovered over Audubon throughout his life. He went to great lengths to keep the truth hidden from a public interested in his story, and his family carried on the lie even after his death in 1851. It was not until Jean’s papers were located in France before WWI that the facts about Audubon’s birth became known.

2. Audubon was not an ornithologist.

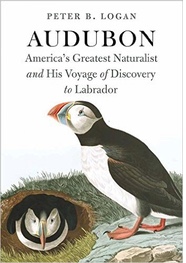

Today, Audubon is best remembered for his vibrant, life-sized, hand-colored prints of North American birds, which were published between 1827 and 1838 in a sumptuous, four-volume work called The Birds of America. It is now the most valuable illustrated book in the world, selling at auction for as much as $11.5 million.

Despite his knowledge and skillful depiction of birds, Audubon was not an ornithologist. “Ornithology” is defined as the scientific study of birds. Audubon was never educated or trained as a scientist and didn’t care for what he called “closet naturalists,” the ornithologists of his day who studied arsenic-dusted birdskins to identify and classify species. Audubon preferred to spend his time outdoors collecting specimens with a shotgun and observing bird behavior firsthand. He conducted the first-recorded bird banding experiment in America and became a first-rate field naturalist. As he was publishing The Birds of America, he wrote a companion text, the Ornithological Biography, a five-volume compendium describing the behavior and geographical distribution of each species depicted in the prints. However, recognizing that he lacked the knowledge to provide a formal scientific description of each species, Audubon hired a Scottish ornithologist, William MacGillivray, to assist him.

3. Audubon was not averse to lying when he had something to gain.

A dynamic and complex personality, Audubon was not above lying when he thought he could benefit and believed he would never get caught. He concocted one of his boldest shortly after immigrating to America from France in 1803. In trying to impress his future wife, Lucy Bakewell, and her family, and still later the public, Audubon claimed that he had studied art at the Paris atelier of the great French Neoclassical master Jacques-Louis David.

This was a bald-faced lie. The Audubon scholar Alice Ford could find no evidence from David’s extant student records that Audubon ever trained with him. Further, ornithologist Charles-Lucien Bonaparte, a nephew of Napoleon’s and contemporary of Audubon’s who knew David, reportedly told an Audubon critic that David had denied that Audubon was ever one of his pupils. While researching my new Audubon biography, I uncovered additional evidence that Audubon’s claim was false.

Yet Audubon repeated the claim in writing multiple times as he was marketing The Birds of America. What is perhaps most surprising is that Audubon evidently never told his wife or sons that he had made it all up. Trapped by a lifetime of falsehoods, he could not bring himself to admit the truth even to them.

4. Audubon was not much of a conservationist.

Although Audubon is often associated with the National Audubon Society, one of America’s leading environmental organizations, he was actually not much of a conservationist. In order to procure the birds that he drew and painted for The Birds of America, Audubon had to kill them. There was really no other way. Primitive photography would not appear until the 1840s, and even then it was suitable only for still portraits. Hand-held telescopes were available, but they were difficult to use for bird watching and of no use in illustrating birds.

Audubon was a crack shot and used his skill with a shotgun to collect his specimens. And he had no qualms about it. During an expedition to Florida in 1831, Audubon wrote to a colleague and said that he had failed to collect enough birds for study “when I shoot less than one hundred per day.” The following year, while exploring Labrador along the northern shores of the Gulf of St. Lawrence, Audubon took an afternoon off from his painting to go shooting on an island where Atlantic Puffins were breeding. He later bragged that he was able to shoot twenty-seven puffins without missing one.

However, Audubon was not obtuse. He recognized the impact civilization was having on the environment. During his 1833 Labrador expedition, he decried the devastation of northern seabird colonies by commercial “eggers” who systematically looted the birds’ eggs. On the northern plains a decade later, he was dismayed to see Bison killed for simple sport. His writings reflect a nascent conservation ethic that acknowledged the role of government in limiting mankind’s destructive impulses.

5. Audubon had nothing to do with the formation of the National Audubon Society.

The first Audubon Society was formed in 1886, thirty-five years after Audubon’s death. Its founder, George Bird Grinnell, was a New York magazine editor who had been schooled as a boy by Audubon’s widow. Grinnell hoped to use the organization to stop the indiscriminate slaughter of wild birds. But he lacked the administrative resources to keep the organization going and closed it after three years. However, similar groups sprang up across the country. In 1905, they banded together as the National Association of Audubon Societies for the Protection of Wild Birds and Animals, the forerunner of today’s National Audubon Society.