Sobibor Was a Hell on Earth, but There’s More to Be Made of It

Sobibor

I didn’t find Sobibor.

It found me.

I accidently stumbled on the story in 1979 while rummaging through the stacks of the Library of Congress. I was in the Holocaust book stacks thumbing through the first Holocaust book I pulled off the shelf when I noticed the word Sobibor. The author simply defined it as a death camp in eastern Poland. Although I knew a few things about the Holocaust, a camp called Sobibor was not one of them.

As I continued to

peruse the stakes, I found Sobibor mentioned in several other books,

and my reporter’s nose began to twitch. If half of inspiration is

showing up, then the other half is listening. I heard the whisper of

Sobibor and started pulling book after book from the shelves and

checking each index for a mention of the camp. After an hour or so,

I found a paragraph in the most exhaustively researched book on the

Holocaust, The

Destruction of the European Jews, by

Professor Raul Hilberg.

As I continued to

peruse the stakes, I found Sobibor mentioned in several other books,

and my reporter’s nose began to twitch. If half of inspiration is

showing up, then the other half is listening. I heard the whisper of

Sobibor and started pulling book after book from the shelves and

checking each index for a mention of the camp. After an hour or so,

I found a paragraph in the most exhaustively researched book on the

Holocaust, The

Destruction of the European Jews, by

Professor Raul Hilberg.

In the 800-page volume, Hilberg briefly sketched the August 1943 uprising at Trebinka, a death camp not far from Sobibor and twice as large before mentioning a similar revolt at Sobibor with even less detail.

I met Hilberg two years later at the 1981 International Liberators Conference sponsored by and held at the U.S. Department of State in Washington. I went to the conference specifically to meet Sobibor survivor Esther Terner Raab, who was scheduled to make a presentation in a workshop on “Uprisings.” I was deeply moved by Esther Raab’s brief, but highly emotional testimony.

After the last historian finished his talk, I cornered Hilberg, and ever so delicately asked him why he had given the escape from Sobibor such scant attention in his book—only two lines in an 800-page volume. He told me that, given the scope of the Holocaust tragedy, the Sobibor escape was of little significance. Next, I asked him if he had interviewed any Sobibor survivors like Esther Raab who had just given a talk earlier that day. He said he didn’t interview survivors because they were too emotional and, therefore, their memories could not be trusted. I found that frank comment interesting, given that the whole Liberator’s Conference was built around the forty-year-old recollections of emotional eyewitnesses.

Hilberg had a point. The escape of 300 Jews from Sobibor is a blip in the context of six million who didn’t escape. So is the Warsaw Ghetto uprising a blip. And the guerilla war of the Jewish Partisans of Vilna, Bielski and Parczew. And the revolt and escape from Treblinka. And the last of the Belzec death camp Jews who refused to be herded into a gas chamber and had to be shot. Each a blip. But when you line them up side by side, add the other small pockets of resistance as well as the individual Jews who escaped captivity, you have a major historical theme that Holocaust historians and researchers paid scant attention to in 1981.

The reason why is clear.

Historical researchers rely on documentary evidence such as Nazi reports, letters, films, directives, trial testimony, and selective diaries. Why bother with eyewitnesses who comment on what they experienced thirty-five years earlier. Everyone knows they are so emotional and have such faulty memories that they are unreliable.

But, there is a deep flaw in the argument. As a historical journalist, I believe in a “collective memory,” which I define as the sum total of individual recollections about an event. Collective memory is self-corrective. The errors and exaggerations of one eyewitness are corrected by the recollections of the others, and the disputed elements of the story surface.

Hilberg’s brief account of Sobibor in The Destruction of the European Jews planted a seed that took root in my heart. It grew into an emotional journey—from Washington to Goiania, Brazil, to Warsaw and Sobibor, to Tel Aviv, Jerusalem, Haifa, and Moscow—to find and listen to Sobibor survivors including Esther Terner Raab tell their stories to a gentile they trusted. The result was Escape From Sobibor, one of the best and most important books I have written, but it left me with a vague feeling of dissatisfaction without telling me why. It slowly dawned on me that something was missing in the book.

Escape From Sobibor is filled with pain and sorrow, inhumanity, honesty, heroism, rage, thirst for life and revenge. What’s missing is hope and healing.

A series of surprises led me to close the gap. First, there was the 1987 CBS Sunday night movie, “Escape From Sobibor.” Viewed by 31.6 million people, it became the networks’ highest rated movie that year. CBS found the response to the film so overwhelming that it offered the movie and script free to schools across the country. New Jersey introduced the movie in public schools as part of its model Holocaust education program. The crawl at the end of the movie said that Esther survived the war and now lives in New Jersey. Students found her and invited her to their schools to answer questions. She agreed. Several thousand letters from children, grades six through twelve, poured into Esther’s home. Each began with the words “Dear Esther.”

After reading them all one summer morning in 1997, I suggested that I weave them into a play. Esther approved saying, “As long as you write a play for adults that children can understand.”

So began my second journey—Dear Esther— my most creative and important play about hope and healing that drew me deep into the heart and soul of a death camp survivor who had the courage and vision to share her journey with the world, and the healing love she got in return.

From school children who had not yet lost their innocence.

Children who offered hope to a deeply troubled adult world.

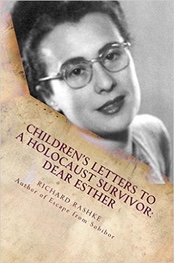

Historic Heroines has now published a collection of those heartfelt letters children sent Esther along with the play, Dear Esther in Children’s Letters to a Holocaust Survivor: Dear Esther.