Think You Know Custer’s Story?

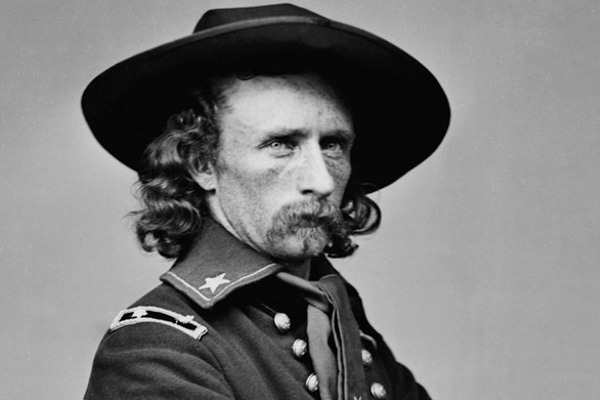

Award winning author TJ Stiles has won his second Pulitzer Prize in History for his recent biography of George Armstrong Custer. Custer's Trials: A Life on the Frontier of a New America reveals a new image of this flawed character, though Custer remains representative of the racism that was pervasive in the period. His other Pulitzer was for The First Tycoon: The Epic Life of Cornelius Vanderbilt. He is also the author of Jesse James: Last Rebel of the Civil War. Mr. Stiles recently explained his motivations for researching the controversial subject of his latest work.

Brian

Johnson: How did you decide to write a biography of George Armstrong

Custer?

Brian

Johnson: How did you decide to write a biography of George Armstrong

Custer?

T.J. Stiles: I see myself as both a writer and a historian. I want to tell good stories and ask big questions. What first drew me to Custer was that his life offers a travelogue of the nineteenth-century American landscape—the astonishing panorama from Wall Street to the Dakota Territory, from dinners with stockbrokers and senators to encounters with pre-industrial nomadic peoples. Then I considered what he did on those journeys.

My broader interests in his era led me to his astonishing range of activities, which many biographers have only briefly addressed, in their rush to get him onto the Great Plains. I began to see both the iconic and the little-known parts of his life as an organically unified story of a man engaged with the many changes sweeping the country, struggling to adapt to the very modernity he helped to create. And then there was the bounty of sources, which allowed me to explore Custer's inner life and intimate relationships as I could not with my previous two books. So I thought I could tell a good story about a compelling character in a fresh way, and illuminate topics rarely associated with him, including literary culture, the rise of finance, gender, and especially race.

What was the research process of this book like? Did your work on Jesse James give you any help?

The research processes for both Jesse James and Custer's Trials began, of course, with the endnotes of the previous books about these subjects and their times, but otherwise they were very different. Unlike Jesse James, Custer came equipped with a wealth of very well-researched biographies and histories. I could draw on excellent books about everything from the battles of Trevilian Station and the Washita to the environmental roots of the Indian wars in Kansas, as well as the volumes of published primary sources. That gave me greater space to investigate more broadly.

In the National Archives, I spent time in less obvious record groups, such as the files of the Freedmen's Bureau and the Department of Justice, which threw new light on Custer's role in Reconstruction. I also traced Custer's troubled relationship with the army chain of command. Digitization of newspapers allowed me to explore his political campaigning and the public reaction, as well as his career as a popular writer and public intellectual.

Another difference with Jesse James is Custer's abundance of surviving letters and other personal sources. I read these with different interests than most previous biographers. In particular, I focused on what his wife, Libbie, wrote about her complicated relationship with Eliza Brown, the self-emancipated woman who ran the Custer household for six years. It took very little reading between the lines to see it as a mix of racial tension with an alliance between two women in a very male environment.

Custer's Trials takes a look at a controversial historical figure. You have found he was more complex than usually given credit. Can you explain how Custer was "a man of his time"?

In the classic The Making of the English Working Class, E.P. Thompson wrote that he wanted to rescue his subjects from "the enormous condescension of posterity." I have found that to be a problem for all my subjects, even the fabulously wealthy and powerful Cornelius Vanderbilt. We get smug when we talk about those ridiculous fools from so long ago, but in context the ridiculous sometimes makes perfect sense. Custer's flamboyance particularly invites snark. But it served him well on the battlefield, where his eye-catching uniform, mounted band, and insistence on horses of uniform color for each company served as command-and-control devices. Examining his conduct on the battlefield, I expected courage, but I also discovered great tactical instincts, self-possession, and an adroit use of the latest technology, such as repeating rifles and rifled artillery. Three years before the Little Bighorn, he met the Lakotas in two perilous encounters, significant battles on the scale of the plains wars, and handled his men skillfully.

On the other hand, context explains but does not excuse. We have to put Custer's views and actions in the context of his contemporaries. For example, he opposed most civil rights for African Americans at a time when many others, particularly fellow army officers, came to very different conclusions. I found interesting contrasts between his writings and those of such Civil War veterans as Ambrose Bierce and Charles Francis Adams Jr. Unlike them, Custer maintained all his antebellum illusions about gallantry and glory. Yet many Americans found Custer's romanticism appealing, as they tried to hold onto their own. In the Indian wars, the most troubling thing about Custer's conduct is that it was not anomalous, but quite typical for the frontier army; he was following orders when he and his men killed all fighting-age Cheyenne men at the Washita. Again, that doesn't excuse him. Ironically, he himself later showed that he could gain control of a hostile village without carrying out a bloody surprise attack.

During the Civil War, as a Union officer Custer routinely freed slaves but he struggled to adopt the civil rights laws that followed. Is this some of the character conflict that was endemic of the country at that time?

No theme in Custer's life was more important than race, especially when we see how it ran through his western career as well. Custer was, in essence, a product of border-state culture, with a fiercely partisan, vocally racist father from Maryland. Custer maintained his father's Jacksonian Democratic views all his life, though his commitment to victory in the Civil War—and his ambition for high rank—led him to embrace emancipation. He developed a close, respectful relationship with Eliza Brown, who escaped from slavery and worked for him for six years. But that makes it all the more striking that he so strongly resisted civil rights. As Libbie Custer wrote, Brown tutored the Custers on the horrors of slavery and spoke out about racial justice.

Many contemporaries in the army embraced Radical Reconstruction. Adelbert Ames, one class ahead of Custer, threw himself into the cause in Mississippi, where he appointed black officeholders and allied with black leaders. Custer, on the other hand, campaigned with Andrew Johnson against the 14th Amendment on the president’s Swing Around the Circle, and sarcastically complained about having to enforce the Ku Klux Klan Act during his deployment in Kentucky in 1871–73, where there was a major federal offensive against white terror. His engagement with race reflected the national political conflict, but he always had a clear choice—and he chose white supremacy.

After the Civil War, Custer was deployed to Kansas in 1866, where he was convicted in a court-martial in 1867 and suspended for a year. What was he convicted of? Does any of this contribute to the idea that he was more complicated than people normally think?

Custer's court-martial in 1867—his second—was the culmination of a spiral of his personal flaws and failure to adapt to the changing times. He wanted very much to engage with the new America on multiple fronts, but didn't grasp rapid shifts in politics, couldn't get his footing in the new economy, made a mess of his marriage, and failed to adapt to peacetime life as a mid-level officer in a large organization, the army. The result was a crisis that led to his trial, but his troubles continued.

He ended the Civil War deservedly acclaimed as a Union hero, but he alienated much of the public by plunging into politics at the side of Andrew Johnson in 1866, against his wife's advice. The Republican press turned on him. He spent many weeks in New York, but his plans for acquiring the wealth in order to move there failed. He hoped to sell a famous race horse he had acquired at the end of the war—inappropriately, in the view of the War Department—but it died suddenly in 1866. He planned to sell his services to the Juaristas in Mexico, but State Department prohibited it. And he endangered his marriage with his attraction to other women. When he entered into the Hancock Expedition in Kansas in 1867, he felt vulnerable and isolated, as his correspondence shows. He desperately wanted to return to his wife, Libbie, to repair the damage. The result was a chain of mishaps. He shot his own horse (his wife's, actually) miles from his column as he hunted a buffalo. The Oglala war leader Pawnee Killer outsmarted him and humiliated him repeatedly. He inflicted outrageous punishments on his men, and ordered deserters to be shot. After failing—even refusing—to engage with Indian forces, he abandoned his post and rode hundreds of miles to see his wife. Along the way, two of his men fell wounded in an ambush, and he declined to assist them.

He deserved his conviction, and his suspension for a year was remarkably light punishment, as General Ulysses S. Grant noted. But Custer nearly endured yet another court-martial because he publicly criticized his conviction in a letter to a newspaper; it took the personal intervention of his patron, General Philip Sheridan, to save him from it. In 1868, he returned to duty and won back the esteem of his superiors in the Washita campaign, but his career survival to that point was a very close thing, and he would repeat many of his missteps, though less dramatically, throughout the rest of his life.