Has the Shaming of Brock Turner Gone too Far?

Related Link When Feminists Take On Judges Over Rape By Estelle Freedman, Stanford History Professor

Historians portray the medieval legal system as inadequate. Policing was rare and makeshift, there was a dizzying array of jurisdictions, and law enforcement was often meted out at the whims of an individual rather than through institutional procedure. The medieval is often contrasted with our current legal system, which is bolstered by regular police patrols and centralized governing procedures.

But the formalization of law enforcement brings its own problems, many of which are being widely discussed in the wake of Brock Turner’s conviction for three felony counts of rape. The presiding judge, Aaron Persky, sentenced Turner to six months in jail, of which he is likely to serve only three. Many have denounced the sentence as far too lenient, saying that he was given a pass because of his white male privilege. These are familiar complaints. Critics of the American legal system point out that poor people of color are punished much more harshly than whites and those with money. Non-violent offenders spend too much time in jail, critics say, whereas the victimization of women is under-sentenced.

Americans tend to feel that our justice system, with its procedures, checks, and balances is not enough. We dream of an alternative, populated by cops who play by their own rules or vigilantes like Batman and Dexter who circumvent the law to vindicate a more meaningful sense of justice. Alienation from the legal system has prompted some to move from the realm of fantasy to reality. See, for example, the reification of conservative monarchist Guy Fawkes as the mascot of the anti-establishment vigilante hacker group Anonymous via Alan Moore’s comic “V for Vendetta.”

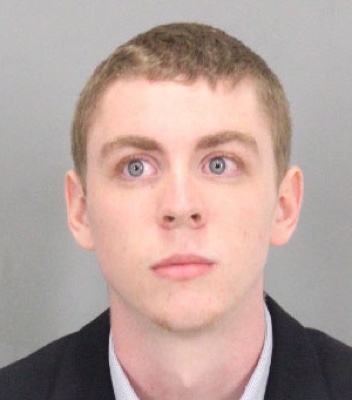

The internet provides fertile ground for vigilantism. Outraged by the verdict and attendant abuses in Turner’s case, people have taken to the internet to extra-legally vindicate justice where they perceive the law to have failed. In response to reporting that refers to Turner’s crimes euphemistically as “sexual assault,” a meme has surfaced labeling him a rapist. Similarly, brockallenturner.com responds to the notion that his athleticism mitigates his criminality: the website shows a picture of Turner exiting the courthouse with a caption that reads “Rapist. Swimmer. But mostly a rapist.”

Such online vigilantism evokes medieval justice, which relied heavily on public shaming. Legal punishments included mutilation and penitential walks (like that shown in Game of Thrones) as ways of marking criminals and subjecting them to ridicule. Perhaps the medieval punishment that comes closest to current internet shaming practices was the pillory. Convicted criminals were displayed in the center of town in wood apparatuses that held them by neck and wrists in a bowing, humiliating position. Usually the criminal would be displayed with a description or a symbol of his or her crime. The butcher who sold rotten meat, for example, would be pilloried and arrayed with the spoiled meat as both an explanation of and punishment for his crime.

Then and now, public shaming serves an important purpose, allowing the public to participate in its own vindication and to give vent to its rage. In the case of extra-legal public shaming it also makes up for inadequacies in the legal system. Memes labeling Turner a rapist correct the improper naming of his crimes by the media and augment his inadequate punishment.

Public shaming has a dark side, however, in that it has no checks and balances and is often susceptible to excess. Medieval and early modern sources describe people being subjected to pillorying without due process and, once there, being subject to unconscionable treatment, such as being urinated upon. The same applies to the Turner case. Turner’s family and friends, Judge Persky and his family, have all been threatened. When news outlets published a letter written in Turner’s defense by his childhood friend, Leslie Rasmussen, a professor unfortunate enough to have the same name also became the object of internet shaming. Much of this shaming includes wishes, threats, and predictions that the object of scorn be raped. In this application of public shaming, the modern has not deviated far from medieval abuses we imagine ourselves to have transcended.

Because it exists outside of due process, internet shaming’s utility is the offer of expedient catharsis and giving voice to the public. It is also dangerous, however, when it victimizes the innocent and contributes to rape culture through the proliferation of rape threats and reinforcement of the idea that rape be used as a punishment for unacceptable speech or behavior. The pillorying of Brock Turner represents the best and the worst of public outcries for justice. At best it acts as a corrective to the failings of our formal legal system. At worst, what starts as a movement to express sympathy and solidarity with victims can spiral into expressions of rage that create further injustice and more victims.