Bernie Sanders and Barack Obama Got the Youth Vote: Did It Matter?

On 5 July 1971, President Richard Nixon certified a twenty-sixth amendment to the Constitution. At a joyous White House ceremony attended by nearly 500 members of the singing group, Young Americans in Concert, Nixon signed the document that legally established eighteen as the national voting age. Though he never publicly endorsed the amendment, Nixon confidently vouched that America’s new electors would infuse the country with “some idealism, some courage, some stamina, some high moral purpose.” Youth suffrage did not wield the revolutionary impact that its devotees predicted. Research shows that 18-to-21-year-olds have the lowest voter turnout rate of any age group. Other studies reveal that the youths who do vote generally hold the same views regarding issues and ideology as their parents and elders.

Forty-five years after its promulgation, the Twenty-Sixth Amendment attracts slight attention because it is not considered a critical law. Public and academic indifference has engendered a uniform explanation of why it was ratified. The consensus asserts the complicated circumstances of the Vietnam War convinced Americans that it was not fair to ask teenagers to fight while denying them the right to vote, and Congress dutifully responded by enfranchising 18-year-olds. Portraying the amendment as the legislative spawn of patriotic sentiment oversimplifies the narrative.

After its introduction during World War II, the youth suffrage issue had been a perennial political lemon. Nearly all the states (except for Georgia, Kentucky, Alaska, and Hawaii) had refused to lower voting-age requirements, and only once, in 1954, had either house of Congress voted on an 18-vote bill. Politicians and parents alike held firm that the storms and stresses of adolescence made teens inherently unfit for voting. During the 1960s, youth suffrage slowly became an actionable legislative prospect. Influenced by the ideology of the era’s social justice movements, 18-vote supporters insisted that voting was a right of citizenship that should not be denied responsible, well-educated adolescents. By the mid-to-late ‘60s, youth activists reckoned they could not topple “the Establishment” without enfranchisement. A spike of intense shocks between summer 1968 and spring 1969 – violent riots at the Democratic national convention in Chicago, bellicose antiwar rallies, and combative confrontations on university campuses – convinced millions of people that a youth uprising was imminent. Public demand that sociopolitical order be upheld became the motivating force propelling Congress to declare eighteen the nation’s voting age. In an era when traditional authority looked ready to crumble and generational revolution appeared a real possibility, many lawmakers argued enfranchising teenagers would save America from disintegration. As Representative Ken Hechler (D-WV) declared, “The 18-vote is needed to harness the energy of young people and direct it into useful and constructive channels. If we deny the right to vote to those young people between the ages of 18 and 20, it is entirely possible that they will join the more militant minority of their fellow students and engage in destructive activities of a dangerous nature.”

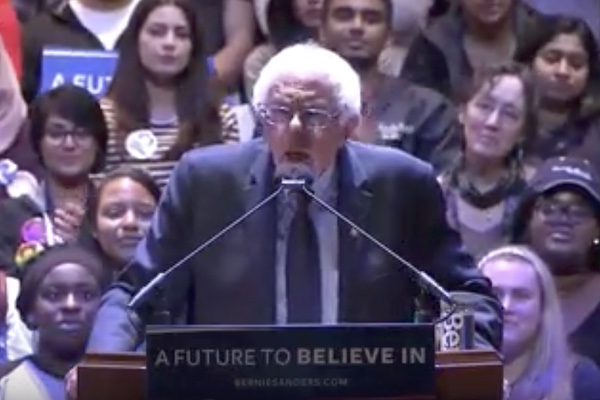

The Twenty-Sixth Amendment unintentionally neutered the group it sought to empower. Prior to the 1972 election, commentators forecast that newly-enfranchised youth would swing the outcome, and party leaders openly wooed young electors. But only 48% of 18-to-20-year-olds balloted, leaving an impression that adolescents were not reliable voters. Declining turnout in the next few elections showed teens to be an unimportant bloc. By the 1980s, youth had become less politically influential than their voteless 1960s counterparts. In marketing, media, fashion, and technology, adolescents remain an earth-shattering demographic, but in politics they have been inconsequential constituency since enfranchisement. Even in 2008, when young people were praised for finally realizing their electoral potential, their votes proved less vital than perceived. Nearly 55% of all eligible voters between ages 18 and 29 cast ballots (their highest turnout since 1972), and they overwhelmingly supported Barack Obama (68%) over John McCain (32%). Democrats gleefully predicted that the demography behind Obama’s “youthquake” might relegate the Republicans to permanent minority status. Many conservatives blamed Obama’s victory on starry-eyed millennials who, according to pundit Ann Coulter, lacked “fully functional brains.” She proposed a repeal of the Twenty-Sixth Amendment to prevent “infantilized, pampered” teenagers from hijacking future elections. Republican hyperventilating and Democratic smugness notwithstanding, young voters did not decide the outcome in 2008. Obama prevailed because he won over large adult constituencies, especially women, minorities, independents, non-evangelical white Christians, and householders earning less than $50,000. As Bernie Sanders recently experienced, young people can energize a campaign, but adult electors determine a candidate’s fate.

Although the Twenty-Sixth Amendment did not become the catalyst for political transformation as prophesized, it registered significant legal impact. Importantly, the amendment clarified age eighteen as the formal commencement of adulthood. Throughout the 1970s, state governments lowered their ages of majority from twenty-one to eighteen to correlate with the federal voting standard. States rationalized that if Congress accorded 18-year-olds greater authority to give consent, then state laws should be changed to allow them to decide matters involving their personal welfare and legal condition. Recalibrating majority ages spawned a rethinking of whether persons in their mid-teens and “tween” years were old enough to make autonomous choices. During the 1970s and 1980s, for example, American jurists established the “mature minor” doctrine; it permits underage children, if deemed capable by a court, to approve or decline medical treatment independent of parents. Similar considerations for youth competence have informed recent attempts to enfranchise 15-, 16-, and 17-year-olds in Great Britain, Australia, and several municipalities in the United States.

Such efforts signify that adolescents are no longer viewed as deviants or delinquents bent on nihilism. Today, teenagers are usually seen as mistake-prone doofuses who annoyingly laze too much and listen too little as they stumble through maturation. Like the Fifteenth and Nineteenth Amendments, the Twenty-Sixth did not shake the fundamentals of social stratification for the newly enfranchised. However, governmental acknowledgement of adolescents as citizens equally capable as adults to give consent offered juveniles prospects for self-determination – electoral, legal, and personal – unknown to previous generations. As a result, adolescent-adult relations became less authoritarian and more democratic. Since the 1970s, the accepted model of adolescence has emphasized that adults nurture the talents and interests of youth rather than dictate the terms of their development. Widespread subscription to the “emerging adulthood” concept has provided young people multiple platforms to cultivate capacities, question beliefs, try on identities, and seize autonomy. That adults once solely focused on imposing order upon the storms and stresses of adolescence now seems quaint. Whether contemporary teenagers should be assigned their social ranks based on ascription or ability remains a question because of the Twenty-Sixth Amendment.