How Should Politicians Address the Legitimate Fears Voters Feel?

Related Link How Americans Responded to the Fear of Enemy Attacks in World War II ... An Interview with Matthew Dallek

“Is it ever moral for a politician to use fear?” I fielded that question at a recent event in which I was discussing my newly-released book, Defenseless Under the Night, which traces the birth of homeland security to the debates between Eleanor Roosevelt, the first lady, and Fiorello La Guardia, New York’s mayor, during World War II. The question forced me to think more deeply about the role of fear in our politics.

Donald

Trump is waging one of the most fear-drenched campaigns in modern

times. Last month, former New York

mayor Rudy Giuliani, a major Trump booster, called “fear… a

legitimate feeling,” and he warned in his GOP convention address

that a Clinton presidency would result in terrorists coming “here

to … kill us.” Trump cast Clinton’s legacy as simply “death,

destruction, terrorism, and weakness.” Trump’s messaging is

almost all about fear –

Donald

Trump is waging one of the most fear-drenched campaigns in modern

times. Last month, former New York

mayor Rudy Giuliani, a major Trump booster, called “fear… a

legitimate feeling,” and he warned in his GOP convention address

that a Clinton presidency would result in terrorists coming “here

to … kill us.” Trump cast Clinton’s legacy as simply “death,

destruction, terrorism, and weakness.” Trump’s messaging is

almost all about fear –

President Obama, he claims, founded the Islamic State, Mexican immigrants, he says, are “rapists,” and Muslim-American communities aid and abet homegrown terrorists.

Since the nation’s inception, fear-based appeals have never really been in short supply in American political discourse. Fear in politics is ingrained in America’s culture. At no time in the mythic days of old did politicians only, simply appeal to lofty notions of people’s better natures. Because campaigns come down to voter choices, candidates for office are inevitably going to frame elections as a choice between better days and a fearful future if the other side were to prevail. Sure enough, optimism and high-minded visions can mobilize supporters and persuade fence-sitters. But the fear of the consequences of the opposition winning power is also a powerful driver of any political (or policy) message.

And yet, how political leaders talk about fear—their own fears and the public’s myriad fears—matters. In thinking about the question of using fear and political morality, I think it’s fair to say that Eleanor Roosevelt harnessed fear during the late 1930s and early 1940s in ways that were by and large both morally just and politically effective. Her approach to the problem of fascist militarism is a stirring rebuke to Trump’s take on border security, terrorism, and law and order.

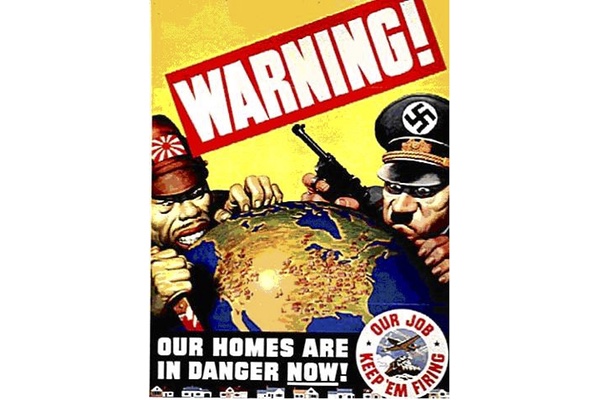

Fear informed the politics of the 1930s and 1940s, of course. The Roosevelt years are typically depicted as a fight against fear. In 1933, FDR, referring to the Depression, said “the only thing we have to fear is fear itself.” In 1941, he vowed “freedom from fear.” But a less-well-known set of fears roiled the United States during the late 1930s and early 1940s: the fears that fascist planes would bomb U.S. cities; that fifth columnists would topple the government; that chemical and biological weapons would kill civilians; that mass panic would upend law and order and perhaps even put a dictator in the White House.

Political leaders reacted differently to these fears for the security of the home front. Some isolationists minimized the threat and said any calls for military preparedness were just war-mongering. Some liberal internationalists, including Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt, insisted that the imminent peril of Nazi Germany required the United States to mobilize militarily and aid the Allies through any means possible short of entering the war itself.

Eleanor Roosevelt thought about fear in complicated ways. “Fear is the enemy,” she declared in the Nation. She meant that fear of fellow Americans would breed internal divisions and make it harder for a unified democracy to tackle its social and foreign policy problems.

At the same time, she insisted that to blithely ignore the serious fascist threat was akin to burying one’s head in the sand. “You don’t want to go to war,” “I don’t want to go to war,” but “war may come to us,” she warned a gathering of pacifists in 1940, using fear of fascism to argue on behalf of mobilizing militarily. But she also empathized with Americans who were afraid, and her public oratory acted at times as a tonic on a bewildered, frightened public.

Speaking on the radio just hours after the bombing of Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, the first lady, who was also serving as assistant director for volunteer participation in the Office of Civilian Defense (OCD), told Americans that it was impossible to “escape the clutch of fear at your heart.” She understood the average American mother’s fears, she announced. Her son was on a naval destroyer. Two of her children lived on the West Coast in harm’s way.

But even though fear was a legitimate feeling, she told Los Angeles residents a few days after the surprise air raids, fear must not govern people’s actions. Act, she urged, “as though we’re not afraid.” That meant doing a job to bolster the war effort, improving life in one’s community, contributing to the war against the Axis Powers. When she visited Tacoma, Washington amid a tide of anti-Japanese hysteria, she purposefully had a photograph taken with a Japanese-American youth group. Her message sought to counteract the hate and fear of Japanese gripping the West Coast. “Give American born Japanese, and even Japanese nationals who lived in this country for years, who have children and grandchildren and who have bought defense bonds—give them every consideration,” she urged.

Ultimately, she didn’t stop the internment camps, nor did she calm people’s most baseless fears including, for example, that Japanese-Americans were fifth columnists. Through her role at the OCD and her years-long campaign to establish a wartime New Deal, however, ER gave millions of citizens volunteer jobs, from child care to fire watchers to first aid workers to planting victory gardens. Her message that people should fear fascists was tempered by a hopeful vision for what democracy should mean in people’s lives.

She said, “One has to face the world as it is and, without discarding one’s ideals, meet the realities of the day and keep on working for what one hopes will be a better future.” While the country waged war, she insisted, the American people and their government also had to strive for a more economically secure, socially just postwar future.

If FDR is often celebrated as the World War II leader who led Americans through fear-drenched times, ER arguably did as much as FDR to help Americans grapple with myriad fears of fascism. By channeling people’s fear in the service of democratic goals, the first lady’s words and actions should resonate with a frightened public in this post-9/11 world. Her role in the debate about fear reminds Americans today that Trump’s fear-mongering is not the only way for political leaders to talk about fear in times of military uncertainty and social unrest.