When is Dissent Treason?

Recently, The Washington Post published the results of a poll of Republicans declaring that a majority viewed immigrants and refugees as a “critical threat” to the nation (October 6, 2016). In the late 1790s, many Americans shared these concerns about recent immigrants. Massachusetts Congressman Harrison Gray Otis warned against “hordes of wild Irishmen” coming to America and Noah Webster charged that for every good immigrant, 3 or 4 dangerous ones arrived –whether they were “convicts, fugitives of justice, hirelings of France, or disaffected offscourings of other nations.” These men and their fellow Federalists even believed that Great Britain, France and elsewhere were deporting their most dangerous citizens to the United States. Americans were particularly wary of refugees from revolutionary France and rebellious Ireland who brought their radical ideas about society and government with them and seemed intent on imposing them on the United States. For men like Otis and Webster, these immigrants would never and could never become truly American.

In

the late 1790s, the United States faced a chaotic world. Europe was

at war. The French seemed intent on exporting their radical

revolution. Many Americans wanted to insulate their country from the

chaos and instability they saw elsewhere. Then in the summer of 1796,

France began the Quasi-War –an undeclared naval conflict—with the

United States. President John Adams sent a diplomatic mission to

France in hopes of easing tensions. France refused to negotiate with

the Americans unless the Americans paid for the privilege. When news

of what would be called the XYZ Affair arrived in the United States,

war fever raged. It was against this backdrop of fear and uncertainty

that the Federalist Party decided to move against whom they believed

were the enemies of the republic.

In

the late 1790s, the United States faced a chaotic world. Europe was

at war. The French seemed intent on exporting their radical

revolution. Many Americans wanted to insulate their country from the

chaos and instability they saw elsewhere. Then in the summer of 1796,

France began the Quasi-War –an undeclared naval conflict—with the

United States. President John Adams sent a diplomatic mission to

France in hopes of easing tensions. France refused to negotiate with

the Americans unless the Americans paid for the privilege. When news

of what would be called the XYZ Affair arrived in the United States,

war fever raged. It was against this backdrop of fear and uncertainty

that the Federalist Party decided to move against whom they believed

were the enemies of the republic.

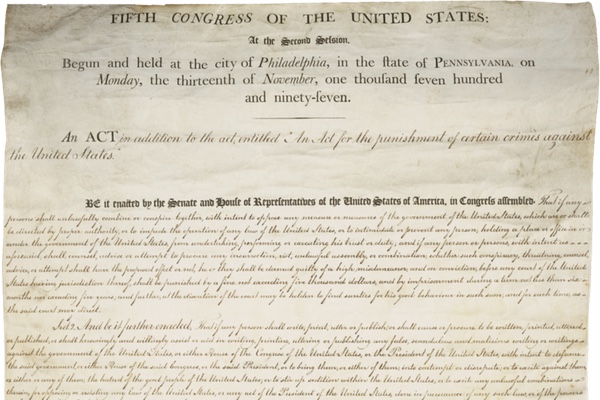

The result was the Alien and Sedition Acts—a set of four laws designed to keep the republic safe. The Naturalization Law increased residency requirements from 5 to 14 years and gave the federal government exclusive power to issue naturalization certificates. Most significantly, it required all non-citizens to register with the federal government. The Alien Enemies Law was a war-time measure which gave the president the power to deport citizens of nations with which the United States was formally at war. Since the United States and France never formally declared war, this law was never invoked. The Alien Friends Law gave the president the power to deport any suspicious aliens without any hearing or access to the court system. Finally, the Sedition Law, the only one of the four laws to act upon American citizens, made criticism of the government a crime.

Federalists were deeply concerned about the loyalty of immigrants. Extending residency requirements and making it harder for aliens to become citizens was one way to protect the nation. Deporting them or threatening to do so was another. While no one was actually deported under the Alien Friends Law, many were watched; many left before they were forced to do so; and some decided not to come to a country where they would just exchange one form of oppression and uncertainty for another. It was not only alien who posed a danger, but Federalists believed that some citizens posed a threat, particularly those who published newspapers which spread radical ideas, advocated opposition to the government, and employed some of those radical immigrants.

The laws were always controversial. Americans went to meetings, approved resolutions, and signed petitions both supporting and opposing the laws as Americans were closely divided. The most famous and infamous protests came from the pens of Thomas Jefferson and James Madison in the Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions, respectively. In Jefferson’s draft of the Kentucky Resolutions, he contended that states as parties to the constitutional compact had the right to judge the actions of the general government. While elections were the first remedy, nullification was another. Madison was more purposely ambiguous in his resolutions –stating that in times of palpable danger states should interpose between the federal government and the people. No states fully supported Virginia and Kentucky and many opposed them. Rather than force the repeal of the laws, Jefferson and Madison would have to wait for them to expire –the Alien Friends law on June 25, 1800 and the Sedition law on March 3, 1801—for their menace to pass.

At its base, the controversy over the Alien and Sedition Acts was about the characteristics of a good republican citizen. Jefferson summed up the dilemma of republican citizenship as a problem of confidence vs. jealousy. Americans understood confidence to mean trusting their leaders to further the common good. Elected officials in turn expected voluntary obedience to the law and government policies from the people. On the other hand, jealousy meant vigilance especially alertness to any abuses of power by government. Federalists favored confidence and Democratic-Republicans privileged jealousy. Federalists argued that confidence gave the government the energy to act when necessary to maintain order and protect the nation. Democratic-Republicans argued that this view gave the government too much unchecked power and would likely lead to violations of the people’s rights. As Jefferson wrote in his draft of the Kentucky Resolutions, “confidence is everywhere the parent of despotism –free government is founded in jealousy, and not in confidence; it is jealousy and not confidence which prescribes limited constitutions....” Jefferson warned against placing unconditional trust in the government and instead urged Americans to be ever watchful of government actions to make sure that rights were not violated and power not abused.

With Jefferson’s victory in the Election of 1800, Federalists became a permanent and weak minority party. Although the people rejected the party that championed the Alien and Sedition Acts, the Federalists’ defeat did not settle the issues debated in the 1790s about the status of immigrants in the United States and the meaning of freedom of speech and the press. Americans debated these issues again during Jefferson’s presidency, during the War of 1812, and continue to do so today.