The FBI Violated a Standard that Goes Back Before Watergate

Those who do not read their history are doomed to repeat it. As former Supreme Court Justice David Souter lamented a few years ago, our nation suffers from civic ignorance. Worse, few know about even recent presidential history. As Souter pointed out, Thomas Jefferson himself warned that “an ignorant people can never remain a free people."

FBI

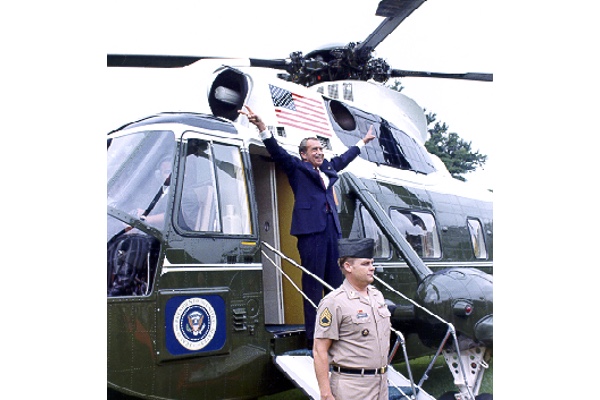

Director James Comey’s recent meddling in a presidential election

should evoke memories of 1972, another presidential election year.

After the break-in at the headquarters of the Democratic National

Committee at the Watergate by burglars affiliated with President

Nixon’s Committee to Re-Elect the President (CRP), the FBI faced a

tricky problem: how to conduct a criminal investigation without

interfering with a presidential contest. How far should the

investigation go? What was fair game and what was out of bounds?

FBI

Director James Comey’s recent meddling in a presidential election

should evoke memories of 1972, another presidential election year.

After the break-in at the headquarters of the Democratic National

Committee at the Watergate by burglars affiliated with President

Nixon’s Committee to Re-Elect the President (CRP), the FBI faced a

tricky problem: how to conduct a criminal investigation without

interfering with a presidential contest. How far should the

investigation go? What was fair game and what was out of bounds?

In 1972, the dilemma manifested itself as a result of money that had been raised by Nixon’s CRP (derisively referred to as “CREEP” by opponents) prior to a change in campaign contribution laws in April 1972. Prior to a certain date, money could be collected anonymously; after disclosure of the contributor’s identity was required. As a result, a flood of money poured into the re-election campaign coffers before the deadline—and questions would inevitably arise as to whether the money was received before or after the cut-off date.

G. Gordon Liddy was a lawyer working for CRP at the time and he handled some of the money and checks that had been sent in with the expectation of anonymity. Liddy, who also worked as one of the White House “plumbers” operation before being sent off the Committee to Re-Elect, made the executive decision to send checks to Miami to be run through bank accounts of some of his recruits who had assisted in some of the plumbers’ illicit jobs, like breaking into the psychiatrist’s office of Pentagon Papers whistleblower Daniel Ellsberg. Liddy’s actions represented a belts and suspenders approach that was not particularly offensive, as the money he was laundering had been received prior to the campaign finance deadline. But he was inadvertently creating a trail that would be uncovered after some of these same Miami operatives were arrested in the Watergate break-in a few months later.

The checks being laundered included contributors from Texas, whose money had been forwarded through a lawyer in Mexico. None of the money was per se used by the Watergate burglars, but it all made its way back to the Committee to Re-Elect the President, which had funded Liddy and his cohorts.

The question for the top criminal lawyer at the Department of Justice was whether to expand the investigation of the break-in to include potential campaign finance violations—a tangential but different inquiry.

John Dean, then the young White House counsel, met with the Attorney General, Richard Kleindienst, and the head of the Department of Justice’s Criminal Division, Henry Petersen, just days after the break-in. Like Comey, Petersen was a person in authority who was affiliated with the opposition party: Petersen was a Democrat in an Administration that was Republican. Petersen had worked for Bobby Kennedy, but he was retained by John Mitchell when he became Attorney General and as a DOJ careerist was promoted to head of the Criminal Division.

Dean related what Petersen said to him about containing the Watergate investigation in his book, Blind Ambition. Knowing there was a potential for overly zealous prosecutors to veer off into the campaign finance question, Petersen assured Dean that the DOJ and the FBI would limit themselves, based on the longstanding tradition of avoiding if possible matters that would appear to be interfering in national elections. The tradition was based on the implicit understanding that the criminal process could be abused in trying to sway elections, especially by the party in power. The policy is an extension of what all prosecutors call “prosecutorial discretion.”

Investigate the break-in, yes. Investigate whether campaign finance laws were violated simply as a result of the Watergate break-in, no.

Petersen told Dean that he had already informed the Assistant United States Attorney General working the case, Earl Silbert, to be careful to stay focused on the matter at hand. “Well, I’ve instructed Earl on the investigation,” Petersen said to Dean. “He knows he’s investigating the break-in. That’s the crime we have in front of us. He knows better than to wander off beyond his authority into other things.”

The Anthony Weiner investigation certainly seems to be a case of the FBI wandering off into a peripheral matter that could be misused to influence the election. The timing alone is highly prejudicial given that the FBI can announce the expanded investigation without having to reveal what it is about due to national security concerns. Comey lambasted Secretary Clinton for her “recklessness,” yet his actions can only be characterized as reckless at best, nefarious at worst. As a top law enforcement officer in a presidential election year, he owed it to the democratic process and to longstanding traditions at the DOJ and the FBI to exercise extreme care when dealing with matters of such gravity, especially at this point in the election process.

Unlike the Nixon Administration, which tried to cover-up its knowledge of who committed the break-in and tried (unsuccessfully) to limit the investigation of the break-in itself, Hillary Clinton has demanded complete disclosure. The mess that has resulted is no doubt to be laid at Clinton’s feet for her decision to use a private server, but until we know more about what is in these nameless emails, it is hard to fail to see this as anything but meddling by the FBI. The delimitation tradition that Petersen followed in 1972 should have been honored in this election absent certain knowledge that some laws were violated, and if that were the case, put the evidence out for the American public to see and to judge in an election that is now upon us.

Because of Comey’s recklessness, we now must guess—a completely indefensible position in which to place the American electorate.