Did You Know the FBI Probe of the Clinton Foundation Began with a Book Written by a Partisan Hack?

Related Link Top 5 Times the FBI intervened to Help the US Right Wing By Juan Cole

On November 1, 2016, just one week in advance of the presidential election, the New York Times reported that over the summer FBI officials had decided, in the heat of a presidential election year, not to pursue a case against the Clinton Foundation and its sources of funding. The case, based out of the FBI’s New York field office, had failed to unearth any substantiated evidence of wrongdoing. Even worse, the preliminary case New York-based FBI agents developed was rooted in news accounts and the partisan political book, Clinton Cash: The Untold Story of How and Why Foreign Governments and Businesses Helped Make Bill and Hillary Rich (Harper Collins, 2015), which claimed the Clintons had accepted foreign funding for their foundation in return for special favors through Hillary’s State Department. Seeing this book for what it really was, Justice Department and senior FBI officials rightly stopped the investigation from advancing. To many, the fact that FBI agents of all people could base an official, if preliminary, FBI investigation on an overtly partisan book seemed on its face absurd and ridiculous. The reality, however, is that this sort of thing is not without precedent. It happened some 75 years before.

In the Fall of 1941, with the Second World War raging in Europe,

President Franklin D. Roosevelt wanted to give the British

aid-short-of-war to allow them to fight the Nazis so Americans

wouldn’t need to. Meanwhile, FDR’s strident and mostly

conservative foreign policy opposition — in the form of the America

First Committee — claimed that any assistance to the Allies would

directly result in American participation in another devastating

world war to the detriment of the country. The national political

debate over American involvement in the Second World War was bitter,

extensive, and only matched historically by the deep divisions

inherent in the later debate over American involvement in Vietnam.

Both sides in the fall of 1941 found themselves in a political

stalemate, with Americans more or less equally divided over the

issue. FDR’s speech writer Robert Sherwood lamented that

“Isolationist sentiment became ever more strident in expression and

aggressive in action, and Roosevelt was relatively powerless to

combat it. He said everything ‘short of war’ that could be said.

He had no more tricks left. The hat from which he had pulled so many

rabbits was empty.” Roosevelt had one more rabbit to pull out of

that hat, however. In an attempt to break this impasse, FDR directed

his attorney general to begin looking into “the money sources

behind the America First Committee.” With (unfounded) rumors

floating about that America First was receiving questionable foreign

(i.e., Nazi) funding, the president thought exposing the issue might

break the foreign policy debate deadlock in his favor.

In the Fall of 1941, with the Second World War raging in Europe,

President Franklin D. Roosevelt wanted to give the British

aid-short-of-war to allow them to fight the Nazis so Americans

wouldn’t need to. Meanwhile, FDR’s strident and mostly

conservative foreign policy opposition — in the form of the America

First Committee — claimed that any assistance to the Allies would

directly result in American participation in another devastating

world war to the detriment of the country. The national political

debate over American involvement in the Second World War was bitter,

extensive, and only matched historically by the deep divisions

inherent in the later debate over American involvement in Vietnam.

Both sides in the fall of 1941 found themselves in a political

stalemate, with Americans more or less equally divided over the

issue. FDR’s speech writer Robert Sherwood lamented that

“Isolationist sentiment became ever more strident in expression and

aggressive in action, and Roosevelt was relatively powerless to

combat it. He said everything ‘short of war’ that could be said.

He had no more tricks left. The hat from which he had pulled so many

rabbits was empty.” Roosevelt had one more rabbit to pull out of

that hat, however. In an attempt to break this impasse, FDR directed

his attorney general to begin looking into “the money sources

behind the America First Committee.” With (unfounded) rumors

floating about that America First was receiving questionable foreign

(i.e., Nazi) funding, the president thought exposing the issue might

break the foreign policy debate deadlock in his favor.

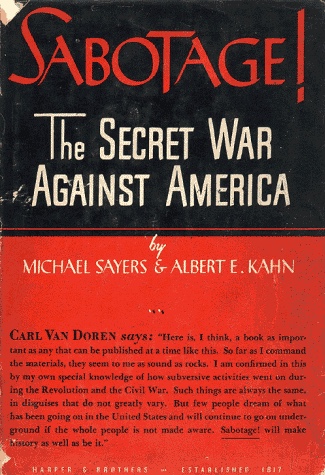

FBI agents thus began an investigation in New York. They based the probe on claims made in a soon-to-be-published, sensational book that the German government was secretly channeling money to fund the America First Committee. The book, co-written by Michael Sayers and Albert Khan, was titled Sabotage! The Secret War Against America (1942). (Ironically, it was published by Harper and Brothers, the corporate ancestor of the publisher of Clinton Cash.) The book’s authors claimed several America First figures had received money from Nazi sources, including one from Ohio, who allegedly accepted $10,000 from the German government to distribute pro-Nazi literature. The authors also claimed that America First took out ad space in an extremist newspaper that also received Nazi funding, the Herald.

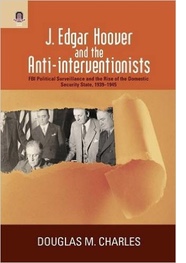

FBI officials believed that if agents could examine the research files used by the authors it would be useful in two ways. First, they believed it would offer them “a broad picture of subversive activities” in America, and, second, it would allow them to build a prosecution of America First. If this avenue failed, FBI officials were told by Harper lawyer Morris Ernst that enough evidence existed to prosecute America First for violating the Foreign Agents Registration Act — the federal law mandating that those receiving money from a foreign power register with the federal government as an agent of that power. Ernst, it should be noted, had an interest in discrediting the America First movement. He had the ear of the president and at one point even suggested the government use tax returns to target the group. At one point he had provided the president with a list of contributors to the America First Committee. In the view of FBI officials, however, Ernst’s other various actions were “aggressive” and J. Edgar Hoover was reluctant to pursue them given their clearly partisan and public nature. Hoover knew not to do anything that might reflect badly on the FBI’s carefully honed public image. Yet FBI agents did attempt to follow up by examining the research file used by the authors of the book.

In this instance, FBI agents were not motivated out of some level of rank partisanship in the New York field office. This is contrary to what happened in the Clinton Cash episode. As one current FBI agent has complained, FBI agents in the New York office were so stridently partisan and anti-Hillary that, in his view, “The FBI is Trumpland.” In the Sabotage case some 75 years earlier, FBI agents investigated under orders from Hoover, who was interested in satisfying the politically partisan interests of the Roosevelt administration. As the only conservative holdover figure in FDR’s government — from the Republican administrations of the 1920s — J. Edgar Hoover had a bureaucratic interest in satisfying FDR’s political and policy interests both to retain his job as FBI director and to expand the FBI’s authority. Hoover’s job and leverage depended on his personal relationship with the president, which, actually, was a close one. Moreover, FBI Director Hoover probably regarded America First, as FDR did, as a Nazi dupe and mouthpiece and thus, in his mind at least, also as un-American.

FBI agents tried for weeks to gain access to Sayers’s and Khan’s research file at Harper and Brothers, but they continually faced one scheduling delay after another. Making little headway in interviewing the book’s authors or even the managers at Harper and Brothers, Justice Department officials eventually assigned the case to its Criminal Division. But the effort to develop something with which to discredit the president’s foreign policy critics came too little, too late because soon thereafter, on December 7, 1941, the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor bringing the United States into the Second World. By the time FBI agents did get the chance to review Sayers’s and Khan’s research file in April 1942 the America First Committee had disbanded and FBI agents had started to question the reliability of the book’s authors owing to their leftist sympathies. In the end agents found the file “to be largely worthless.”

This incident, though, is instructive in several ways. It shows, on the one hand, that historically the FBI is not above engaging in politics. On the other hand, the way the FBI went at it in 1941 was strikingly different than in 2016. In 1941, under J. Edgar Hoover, the FBI was a tightly run ship. Nothing happened without Hoover’s assent. FBI agents did not pursue investigative leads based on their own personal political biases, and any agents who got out of line were harshly punished by the iron-fisted Hoover. Yes, FBI agents pursued an investigative lead in 1941 based on a sensationalist book with an underlying political purpose (to discredit America First) but those agents were following orders from Hoover.

In 2016 FBI agents out of the same New York field office on their own rooted their investigation of the Clinton Foundation firmly in a book that satisfied their own, personal political partisanship. And when their superiors shut down their efforts, according to news reports, anti-Hillary FBI partisans begin leaking information. Unlike Hoover, FBI Director James Comey apparently has something less than firm control over his FBI. Even more, his willingness to testify before Congress about the bureau’s investigation of Hillary Clinton’s emails when no charges were leveled, and then to update Congress on further investigative developments close to a presidential election, broke with decades of FBI tradition. This raises ethical questions. One can only imagine the impact this example of apparent partisanship has had on the bureau’s agents. While it is absolutely true Hoover’s FBI leaked information to sympathetic reporters and friendly legislators to advance its own interests, it is also true that Hoover maintained strict control over this sort of behavior and always did it quietly and obsequiously. Comey, on the other hand, seems to be heading up an FBI going rogue and leaking like a sieve. Comey’s blunders and failed leadership make the likes of J. Edgar Hoover seem somehow stable – and that should send a chill through everyone’s spine.