Meditations of an Old Historian on the Late Election

If anything positive can be said about the appalling results of the election it is that it has stirred some latent public interest in history. At social gatherings ever since I have been asked whether in my professional opinion there has ever been a worse one. My automatic answer at first was no, that we had really hit bottom this time. But I now realize that I overlooked the little matter of the election of 1860 when we literally became, for a time, “two nations.” We did emerge with the Union preserved, getting stronger, and free of slavery – but only after four years of bitter, bloody civil war. I don’t want to “win” any future election that way.

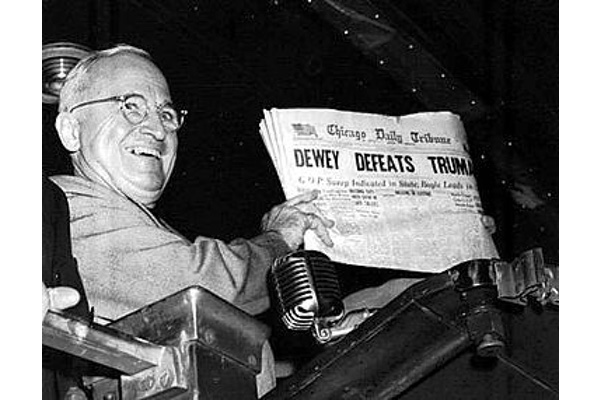

So what, for me, is the most striking thing about this election is that it is such a tremendous upset. There have been plenty of consequential elections that shifted politics into new channels—1828, 1896, 1936, 1968, 1980 come to mind immediately. Some were even “landslides.” But the one that is almost a twin of last week’s was 1948, which I lived through and voted in (for Socialist Norman Thomas.) What they have in common is that they totally overturned the predictions of the so-called experts, and of course, were vastly different in their impact. The surprise election of Truman over Dewey was the postwar renewal of the 1936 ratification of the New Deal.

In 1946, in the immediate reaction to the dislocations and upheavals of demobilization and the whipped-up unity of wartime chauvinism, voters elected what Truman was to call the no good, do nothing Republican 80th Congress which took as its primary objectives restoring the economy of the 1920s in which the government lavishly rewarded big business; crippling labor unions; and pursuing suspected Reds in government. Truman’s win two years later, even while it preserved McCarthy-driven Red scares in the early stages of the Cold War, opened the door to the Eisenhower era of reasonable conservatism. It was likeable “Ike” who said that anyone who hoped to abolish Social Security should have his head examined. It was the giant corporations in the auto and steel and associated industries who signed a truce with labor statesman Walter Reuther, representing auto workers who made up a large part of the movement representing 40 percent of the American work force.

These developments opened the door to good things—decreasing inequality, desegregation of the armed forces and the schools, the emergence of the African-American people’s struggle for their rights, the victories of the Fair Deal, the New Frontier and the Great Society. These were the very things that were challenged in the election of 1968, fought over in the nineteen-seventies, and whose destruction was begun after Reagan was elected in 1980. Trump’s choice has sealed a final victory in the long, hard descent into reaction. In sum, 1948 and 1970 marked the triumph of progressivism more or less in the first half of the twentieth century, and its cold-blooded murder from 1980 onward.

I do take a certain comfort in the confounding of the priesthood of pollsters. A precedent was set in 1936 when a popular news magazine, the Literary Digest, ran a poll that predicted with certainty that Republican Alfred M. Landon would win in 1936. Later they published an edition with the cover page proclaiming IS OUR FACE RED—and soon after went out of business. The “science” of measuring public opinion was then in its infancy, and its growing corps of experts later mocked the magazine’s method, which had relied heavily on postcard and telephone inquiries to affluent subscribers. With the increasing sophistication of computers, and the enormous quantities of available data, the possibilities of estimating election outcomes from small samples of selected populations have grown exponentially and resulted in the Niagaras of predictions clogging the airwaves throughout the ordeal of our impossibly stretched out campaigns. I distrust our over-reliance on digital juggling, conceived originally and primarily for commercial marketing, and very often unfairly influencing election outcomes. A successfully marketed but bad product only harms its buyers, who may eventually catch on and stop buying it. A successfully marketed bad President harms the whole country, and even if the voters soon discover their mistake, we are stuck with him or her for a whole election cycle.

For those of us historians who keep the credo of progressivism there is large-scale fallout from these last decade’ of relative defeat. There’s no longer the animating faith that time is on freedom’s side. The notion of automatic progress is dead, as are most other kinds of sunny nineteenth century determinism—Marxism, with its withering away of the state; Social Darwinism’s premise that evolution works always towards a higher form of civilization and society; evangelical Christianity’s postmillennial ideal that Christ would return after a thousand years of a cleansed and peaceful world made ready for him by the reform efforts of devoted Christians. We will, in my view, want to incorporate into our teaching and writing the notion that merely keeping the earth and its peoples decently sane, just, and free—or in the current state of the environment keeping it at all—is a never-ending battle against high odds with no guarantees of success. The quality of heroism belongs to those who hang on and persevere in their efforts, and sometimes win—for a while.

This is not the place nor the moment to offer prescriptions for action, of which I have none yet. Nor do I need to present my personal historical analysis of the many factors that tumbled us into the pit out of which we must begin to dig ourselves. There are plenty of thoughtful examinations going around on this very site that I would want to digest first.

What I am certain of is the continuing dismay of knowing that while Trump lost the popular vote, there were still some fifty-nine million Americans who voted for him. This is not the nation that I thought I was living in and it’s absolutely shattering. How could I—how could we, supposedly so familiar with our past, have been so blind?

I know that there are conciliatory voices saying that we well-educated and well-off liberals made a great mistake in writing off all Trump supporters as xenophobes, racists, ignoramuses and religious zealots, while ignoring their economic pain and sense of lost status. I can’t quite agree, even though I know at least one or two. They may be entirely decent people in their private lives, but they gave their votes, and what is worse, they gave recognition and legitimacy and worst of all as it turned out, the most powerful office in the world to a man who was all of those things and shows not the remotest sign that he is going to change. They looked away from that reality and they must be held accountable. So must we who voted against them, but our mistakes cannot be equated with the ugly divisiveness and long-lasting venom of theirs. We didn’t create that; it was there, waiting to be activated.

For that reason, calls on us to engage in constructive dialogue that will reunite our “two nations” leave me cold in their present form. If it’s to be an honest search for common ground, they need to admit their error, too. The name-calling didn’t come entirely from the liberal side. Remember their rhetoric, in which we were collectively branded as godless libertines, enablers of terrorism, traitors, protectors of criminal aliens, enemies of Christianity and longstanding Western (i.e., white) civilized norms. When they, or a large majority of them, are as ready to confess error and start with a clean slate as are those who speak up for “healing” then it may be time to listen. Until then, however, it’s my conviction that the only honorable course of action is nonviolent resistance on every political, economic and cultural front—demonstrations, boycotts, letters and petitions, coalitions of opposition in Congress, actions in state legislatures. The America which has had its bad moments, but was the admiration of the world in some of its best, is worth fighting to recapture.