The Loser Takes It All

The US Electoral College system is a version of “first-past-the-post” where the loser can – and sometimes does – win. Now, it needs to be noted from the start that (at the time of writing) not all of Hillary Clinton’s and Donald Trump’s votes have been counted and verified, and the Electoral College will not vote until December 19th. However, if all goes according to plan, barring bizarre irregularities or a landslide of faithless electors, then Donald Trump will assume the presidency on 20 January 2017, as the 45th President and the fifth holder of that office to have finished second in the popular vote, but won the election (at least on their first attempt).

The first occasion on which the second most popular candidate won the presidency takes us back all the way to 1824, when John Quincy Adams finished second with 30.9% of the popular vote to Andrew Jackson’s 41.4%. Here Jackson was the clear winner by plurality, yet he failed to amass over half of the Electoral College votes, as four different candidates won votes from the Electoral College. For the first and, so far, only time, the presidential contest was thrown into the House of Representatives. Even here there was no overall majority winner in the popular vote among the individual representatives, with 41% voting for Adams and 33% for Jackson, but Adams clinched election because each state only had one vote in the House, so Adams’s 54% beat Jackson’s 29% (an echo of the winner-takes-all issue that causes the Electoral College to create second-place winners).

Adams’s election was the largest proportional popular vote deficit ever for a winning candidate – and four years later he was ousted from office in a Jacksonian landslide. Adams’s presidency was tainted by the idea that he had been elected as a part of some “corrupt bargain” between Adams and one of his rivals for the presidency, Henry Clay, and the machinations behind his election undermined his legitimacy from the get go. Indeed, as the Edinburgh Annual Register put it in 1825, “This result … gave grave offence to the democratical party throughout the Union, by whom Jackson was chiefly supported, and who represented it as an act of contempt of the national voice by those who were most religiously bound to respect it.” Four years later, in 1828, Jackson won as the first “Democratic Party” presidential candidate (a party that did not technically exist in 1824) and thus, in some sense, he had become four years earlier the first of five Democrats to lose the presidency but win the popular vote.

In 1876, a decade after the Civil War had ended and the nation was still divided about how to reconstruct the union, the next of the second-place winners took the keys to the Executive Mansion. If 1824 seemed like a “corrupt bargain” it ranks second to the Machiavellian disregard for the views of the electorate shown in 1876. Here Republican Ohio governor Rutherford B. Hayes saw off the challenge of Democratic New York governor Samuel Tilden. Tilden won the popular vote by 50.9% to Hayes’s 47.9% but, more interestingly, lost the Electoral College by a wafer thin 184-185. The result in four states: Florida (more on this one later), South Carolina, Louisiana and Oregon were all contested. In a resounding echo of 2016, but this time across the southern states in particular, there were cries from Republicans of the vote being rigged by the Democrats. Reviewing the situation some months later, the Manchester Guardian noted grimly that “…it is evident from the disclosures already made that the late presidential canvass exceeded anything that has been known in the use of corrupt and violent means” (15 February 1877). Hayes needed all of the contested states in order to win. Ultimately he took them all narrowly – in South Carolina and Florida by fewer than 1,000 votes. The result was not just a subversion of the popular vote, but also doomed the African-American voters in the states of Florida, South Carolina and Louisiana to decades of disenfranchisement. Hayes agreed to remove federal troops (supporting African-American voting rights in the South) from these contested states if they agreed to back his controversial victory. With the so-called “Compromise of 1877” Hayes narrowly secured the presidency, but lost the South to Democratic dominance for almost a century to come.

The third instance of the second-place winner came relatively soon afterwards, in perhaps the least studied of the four “historical” elections, the election of 1888. In this contest, incumbent Democratic president, Grover Cleveland, saw off Republican Benjamin Harrison in the popular vote by a narrow 48.6% to 47.8%. However, the Electoral College vote went firmly against this, awarding Harrison 233 votes to Cleveland’s 168. In an eerie augury of the eve of the 2016 election, on 6 November 1888, the New York Times reported thus: “The close of the campaign finds the Democrats serenely confident of the result and the Republicans lifting up their voices and crying to high heavens to protect them from frauds. They are in no peril of suffering frauds.” However, in fact, it was the Republicans who were most widely accused of trickery and fraud, with Harrison’s campaign accused of buying off voters in his native Indiana. For a third time, the election was won by the popular loser and the winner’s legitimacy was tarnished.

It took more than a century for the fourth occasion when the popular will would not match that of the Electoral College. In November 2000, Democrat Al Gore won 48.4% of the popular vote to Republican George W. Bush’s 47.9. However, Bush just swung the Electoral College vote 271 to 266 following an infamously contentious battle in the state of Florida. Here, Bush beat Gore by just 537 votes after the 5,825,043 dubiously-punched ballots had been tallied. During the recount controversy, Gore called for calm, but warned ominously: “Ignoring votes, means ignoring democracy itself… if we ignore the votes of thousands in Florida in this election, how can you or any American have confidence that your vote will not be ignored in a future election” (Washington Post, 28 November 2000). The controversy focused around the way votes were counted in the state which, as many critics noted, was governed by Bush’s brother Jeb. In the end the US Supreme Court resolved the issue in Bush v. Gore (2000) when they decided by a vote of 5-4 to stop the recounts and let the result stand. For the fourth time, a presidency began with cries of foul play – though unlike the previous three second-place winners, Bush went on to win the popular vote in the subsequent 2004 election.

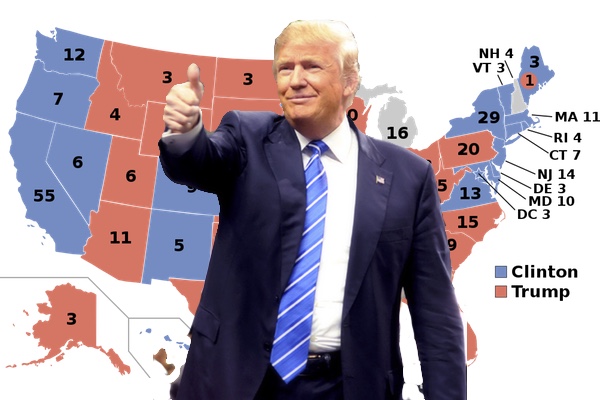

Fast forward sixteen years and we appear to be at occasion number five in US history where, as it stands, Republican Donald Trump looks set to win the presidency via the Electoral College vote and in spite of the popular vote (even if Clinton won the currently contested states, she would still fail to take the Electoral College, and only outlandish miscalculations in the three states still examining votes would hand a national popular vote win to Trump). This time, the cries of foul play and a fixed system came more before the election than after, and – ironically – from the second-place winner’s camp rather than the first-place loser’s. The New York Times claimed on the eve of the election, that – whoever won – the system was “rigged” – by state governments, Russian intelligence, the FBI director, and partisan media, among others (7 November 2016). Yet, despite the indications of almost every opinion poll up to the closing of the polling stations, again the Electoral College system subverted the popular will of the American people. Had the Republicans looked to the past subverted popular elections, they would have seen that any time such an election involved a Republican candidate, their candidate went on to win.

No doubt some will again rally behind the idea of reforming the voting system for the presidency, abolishing the Electoral College and moving to a popular vote. Those opposed to reform will argue that the Electoral College protects the voices of the smaller states, ensures that candidates have to form nationwide “concurrent” majorities, and avoids the nightmare of a national recount. Those in favor of reform will suggest that the Electoral College can (as shown here) subvert the will of the majority, gives unwarranted power to “swing states” like Florida, dampens the challenges from third party candidates, and disillusions and disenfranchises voters in “safe” states (such as Republicans in Hawaii, or Democrats in Wyoming). Yet, the debate over reform or abolition of the Electoral College has been raised hundreds of times over the years to no avail. And, let’s be fair, those amateur psephologists (election geeks) among us might see the flaws in the system, but it does give us a lot to talk about.