Can Republicans and Democrats Treat Each Other with Respect?

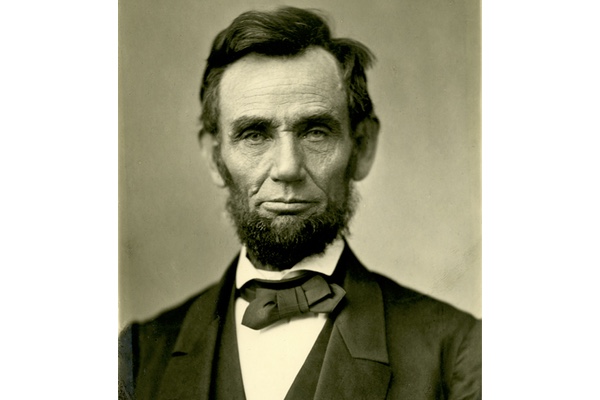

Both Hillary Clinton and Donald J. Trump appealed to Abraham Lincoln’s life and ideas at various points during the recent campaign. Now, in the aftermath of this controversial election, it’s time to heed his advice. Indeed, Americans on both sides of the divide today would do well to reflect on how Lincoln’s approach to politics matured throughout his career.

As

a young man, Lincoln strove to win votes however he could. While

campaigning for the Illinois state legislature in 1832, he once had

to break up a fight in the middle of a speech he was giving.

According to one witness, Lincoln caught “a man by the nape of the

neck and a[ss] of the breeches and toss[ed] him 10 or 12 feet,

easily.” This act “made him many friends,” but not enough to

carry the election. Two years later he won thirty votes by cradling

more wheat than some farm laborers could. That year he won.

As

a young man, Lincoln strove to win votes however he could. While

campaigning for the Illinois state legislature in 1832, he once had

to break up a fight in the middle of a speech he was giving.

According to one witness, Lincoln caught “a man by the nape of the

neck and a[ss] of the breeches and toss[ed] him 10 or 12 feet,

easily.” This act “made him many friends,” but not enough to

carry the election. Two years later he won thirty votes by cradling

more wheat than some farm laborers could. That year he won.

By the 1840s Lincoln found that his sharp wit could carry more votes than his muscle. In 1842, he and his sweetheart, Mary Todd, anonymously wrote several scurrilous newspaper articles about James Shields, a Democratic politician in Illinois. Shields was so angered that he challenged Lincoln to a duel. As the person challenged, Lincoln could determine the rules of the engagement. Since he was 6’4” and known for his wrestling prowess, while Shields was much shorter (and much handier with a pistol), Lincoln stipulated that the two men would stand in a small area and fight it out with cavalry broadswords. If one of them accidentally stepped on the line between them he would “forfeit . . . his life.”

Eventually Shields determined that honor had been met and that the duel was unnecessary. But this incident played an important role in Lincoln’s political life, teaching him that in political debate one should challenge an opponent’s ideas, not to make ad hominem attacks.

Throughout the Antebellum period Southerners sought to silence any opposition to slavery. Congress imposed a “gag rule” on antislavery petitions. One state criminalized speech that had “a tendency to promote discontent among free colored people, or insubordination among slaves.” The punishment for breaking the law ranged from three to twenty-one years in prison at hard labor, or even death. And mobs in both North and South killed white abolitionists, free blacks, and slaves with impunity.

Lincoln addressed the South’s propensity to silence the North in a lecture he delivered at the Cooper Union in New York City in February 1860. He pointed out the ways that Southerners used epithets to refer to Republicans, denouncing them “as reptiles, or, at the best, as no better than outlaws.” Indeed, he continued, “such condemnation of us seems to be an indispensable prerequisite—license, so to speak—among you to be admitted or permitted to speak at all.” Lincoln asked them whether this approach to political speech was “quite just to us, or even to yourselves.”

Lincoln was making an important political point in this final statement. From his perspective, Southerners were depriving themselves of an opportunity to hear an opinion that might be true or persuasive. Pointing to the actions of the radical abolitionist John Brown, Lincoln warned Southern leaders that if they did not permit antislavery voters to voice their opinions peacefully through the political process, that violence like that of John Brown would be their only other recourse. Political dialogue and disagreement, in short, was the best way to engage with an opposition.

In the last two lines of the speech, Lincoln called on Republicans to believe that their arguments were winnable, and to make them despite the fact that they might face personal risks. “Neither let us be slandered from our duty by false accusations against us, nor frightened from it by menaces of destruction to the Government nor of dungeons to ourselves,” Lincoln told the crowd. “LET US HAVE FAITH THAT RIGHT MAKES MIGHT, AND IN THAT FAITH, LET US, TO THE END, DARE TO DO OUR DUTY AS WE UNDERSTAND IT.”

Throughout the Cooper Union address Lincoln urged his listeners to avoid name-calling and superficial arguments. He recommended empathy for political opponents so that people could compromise when possible. And ultimately he argued for citizens to fight for what they believed was right—not fighting in the literal sense, but through speech and persuasion. Doing so would reverse the old aphorism, “might makes right.”

Lincoln’s political wisdom has something to offer Americans of all political stripes in 2016. In the aftermath of the election we have seen incredible anger and frustration on both sides of the political aisle. We have white high school students telling their peers of color that they will be deported, while some Hillary voters proclaim that every Trump voter is racist, misogynistic, sexist, and xenophobic. Since Nov. 8 we’ve seen acts of hate and violence by extremists on both sides. Yet name-calling or trying to silence one’s opponents will not resolve anything. It is better to engage with one another peacefully, introspectively and empathetically—to persuade with actual arguments and understanding—and ultimately to hope that right will make might. As Lincoln said at the end of a vicious and bloody civil war, let us have “malice toward none” and “charity for all.”