So How Did It Work Out After All Those Elections When the Popular & Electoral Votes Were Split?

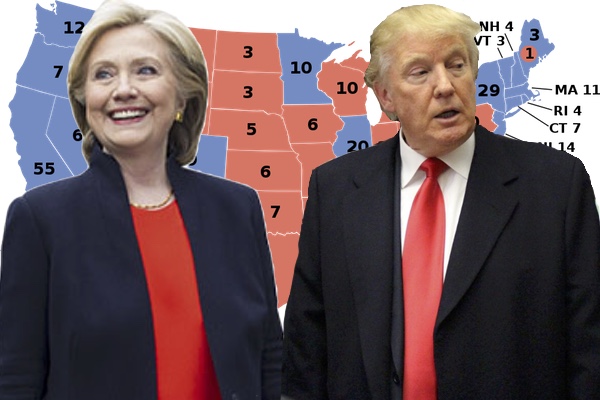

With the conclusion of the 2016 presidential contest between Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump, the United States saw for the fifth time in its history an election where the victor won the electoral vote but lost the popular vote. Contentious and close elections are nothing new to Americans, but these electoral vs popular vote divides are rare. Yet when they have happened, how has it all worked out? A survey of their history is instructive and, while the past does not necessarily predict the future, they may suggest how things potentially could unfold.

The first of these split results was the presidential election of

1824 in which five candidates of the only existing political party —

Thomas Jefferson’s Republican party, as the Federalists went

extinct — vied for the top prize. Among them were William Crawford

of Georgia (who became incapacitated with a medical issue), South

Carolina’s John C. Calhoun (who would settle for the vice

presidency), and Kentuckian and Speaker of the House Henry Clay (who

came in third). Leading the horse race were Secretary of State John

Quincy Adams and General Andrew Jackson. A military hero and popular

figure from the backcountry, Jackson won 153,544 popular votes and 99

electoral votes. Adams, son of the 2nd president and a man who

embodied the political establishment, won 108,740 popular votes and

the second most electoral votes at 84. Given the four-way election,

however, nobody won an electoral majority, throwing the decision to

the House of Representatives, which gave Speaker Clay significant

leverage. Because Adams and Clay both supported federal funding of

internal improvements in the country — developing infrastructure

like roads and canals — and Jackson did not, the House selected

Adams as president.

The first of these split results was the presidential election of

1824 in which five candidates of the only existing political party —

Thomas Jefferson’s Republican party, as the Federalists went

extinct — vied for the top prize. Among them were William Crawford

of Georgia (who became incapacitated with a medical issue), South

Carolina’s John C. Calhoun (who would settle for the vice

presidency), and Kentuckian and Speaker of the House Henry Clay (who

came in third). Leading the horse race were Secretary of State John

Quincy Adams and General Andrew Jackson. A military hero and popular

figure from the backcountry, Jackson won 153,544 popular votes and 99

electoral votes. Adams, son of the 2nd president and a man who

embodied the political establishment, won 108,740 popular votes and

the second most electoral votes at 84. Given the four-way election,

however, nobody won an electoral majority, throwing the decision to

the House of Representatives, which gave Speaker Clay significant

leverage. Because Adams and Clay both supported federal funding of

internal improvements in the country — developing infrastructure

like roads and canals — and Jackson did not, the House selected

Adams as president.

The result was a failed Adams presidency. He had won neither the popular nor electoral votes, and only became president thanks to Henry Clay’s influence; Clay was then made Adams’s secretary of state. Many perceived these developments as a “corrupt bargain” in which the presidency was stolen from Jackson. As such, and given Adams’s lack of domestic political skills and his standoffish personality, his domestic agenda failed. Internal improvements were to be funded by a high tariff on foreign imports, but the law that was passed was a bad one and negatively impacted the economies of different sections of the county. In the subsequent presidential election, Adams lost badly to Jackson who now headed what would be styled the Democratic Party.

The next divided election was the 1876 Hayes-Tilden election, in which the Republican governor of Ohio, Rutherford B. Hayes, won 48% of the popular vote to Democratic governor of New York Samuel J. Tilden’s 51%. Even more, Hayes won 165 electoral votes with disputed votes in Florida, Louisiana, and South Carolina while Tilden came up one shy of a majority at 184. Given this peculiar result and because there was no tie, the Constitution did not offer a resolution. The remedy was the convening of a special federal electoral commission to make a choice and in what has been described as the Compromise of 1877 Southern Democrats supported a Hayes presidency if, among other things, Union troops were removed from the South. This resulted in the end of Republican-led reform efforts to ensure near political equality among African Americans in the South. After 1877, voting rights among African Americans were erased in piecemeal fashion, racial segregation was implemented, and white violence but especially lynchings against African Americans increased significantly.

It only took ten years until Americans saw another divided election. In 1888 Indiana Republican Benjamin Harrison sought to unseat the Democratic President Grover Cleveland. Few issues divided Republicans from Democrats at the time, so the election centered on the sticky issue of the tariff. Democrats favored a low tariff while Republicans favored a high one, and during the election a scandal of sorts erupted when the public got whiff of apparent British interventions and influence in the election over tariff negotiations. The hint that the British backed Cleveland alienated the Irish in New York, costing Cleveland the support of New York, his home state. In the electoral vote, Harrison soundly beat Cleveland with 233 votes to 168. But Harrison came up short in the popular vote, winning 47.9% of it to Cleveland’s 48.6%.

Harrison won the presidency and the GOP took control of all branches of government viewing their win as a mandate. Among other issues, they passed the highest tariff in American history to date. This resulted in GOP mid-term election setbacks. They lost the House to Democrats and reduced their majority hold of the Senate. Then, in the 1892 presidential election, Harrison and Cleveland faced each other again — and again the main issue was the tariff — but this time Cleveland regained the White House while the Populist reform movement among farmers, labor, and reformers began developing rapidly.

The fourth divided election, as we all know, was the 2000 George W. Bush versus Al Gore election in which Gore won the popular vote by 542,179 yet lost the electoral vote 271 to 266 given voting irregularities in Florida and the intervention of the Supreme Court in the recount. The results were a GOP president embracing big government, insurgent war, playing on the politics of fear, while focusing on energizing his base by stressing social and “moral” issues, such as opposition to gay marriage. By the 2006 off-year elections, as Bush became more and more unpopular given his failing wars, the Democrats won big and Barack Obama began his political ascent.

So what’s in store for President Donald Trump? He lost the popular vote, and led a campaign based on sexism, racism, misogyny, Islamophobia, and xenophobia. Can Trump unite Americans or has he irreparably divided them? Trump has promised to improve American infrastructure, like John Quincy Adams, but can he, and will the GOP, deliver? Trump’s voters reacted negatively to the advancement of civil rights, so will those decades-long efforts see a setback like in 1877? Trump has broken with the GOP over free trade and torpedoed the Trans-Pacific Partnership, so where will we stand on issues of trade versus protectionism? Finally, given our recent history of endless wars, while Trump proclaimed himself the most militant person ever, where will this lead us? All of these questions, of course, remain unanswered but history tells us that divided presidential election results typically lead to chaotic political results. Will this pattern hold? Only time will tell.