The Wall Trump Should Build Is Between His Personal Assets and the Public Interest

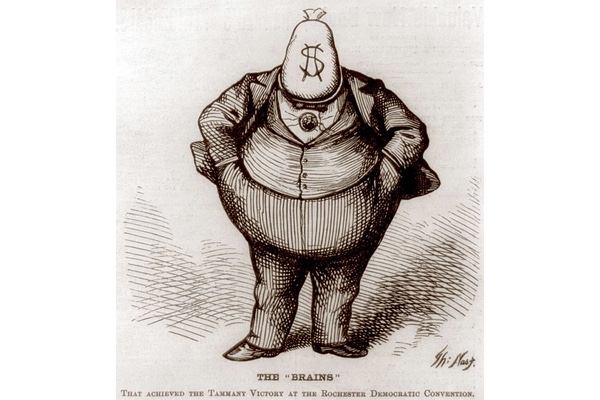

Illustration by Thomas Nast, ridiculing the influence of money in 19th century politics

Recently, I received in the mail a notice from the city of Pittsfield, Massachusetts that, as a member of the Pittsfield Historical Commission, I had to complete my annual review of conflict of interest rules and laws.

Dropping off the signed form at the city clerk’s office gave me pause: Why would I, a volunteer member on a small municipal commission, be subject to conflict of interest rules and regulations, but not the President of the United States?

On the one hand, it’s discouraging that it’s even necessary to remind people that service such as mine is not to enrich oneself, but to fulfill objectives on behalf of a larger community. As a public servant for almost 40 years, I have had to abide by many conflict of interest rules and laws, such as filling out financial disclosure forms and refusing gifts over $50 from any foreign entity.

On the other hand, though, I do understand the need for promoting the public’s trust and confidence in the institutions that serve them and in the people who run those institutions. The motivations in making decisions should be based on the merits of the issue at hand, weighing the benefits and costs to the greater public. We are, after all, human and susceptible to temptation, so such rules and laws are needed to draw the lines clearly for public servants. On more than one occasion over the course of my career, I had cause to refer to the Office of Government Ethics to get a ruling on situations that arose within our work.

I also had good role models. Our Ambassador to Canada, and former Governor of Massachusetts, the late Paul Cellucci, beamed when he showed off the high-end driver he received from the professional golfer Vijay Singh, but he also quickly went to his checkbook to reimburse the cost of the club. Singh earned his visa renewal at the Embassy on his own merit, not on the gift of a golf club.

In my home town of Pittsfield, it does not take much research to uncover past dealings that jar our 2016 sensibilities regarding strict separation of business dealings with public service. In the early 1800s, the first mill operators appealed to their congressman in Washington, Henry Shaw, to support a tariff to raise the price of the imported goods, and help their products compete. A supporter of Henry Clay’s “American System” that included a tariff on imports, Shaw voted for its passage in 1824. The next year, Shaw (who happened to be the humorist Josh Billings’s father) took full advantage of the tariff he helped pass when he led a group of investors to buy land south of Pontoosuc Lake and build a woolen mill, the Pontoosuc Woolen Mill. The national politician Henry Clay returned the favor to Shaw whom he visited on a trip to the Berkshires that, naturally, included a tour of his mill.

Thirty years later, another politician, Thomas Allen, the grandson of a Congregational minister who helped recruit soldiers during the Revolutionary War, moved to Missouri where he made a fortune as an early railroad builder, becoming president of the Pacific Railroad in 1850. The same year, he won election as a state senator and used that position to secure land grants from the state legislature for his railroad. Allen kept his ties to Pittsfield, and used some of his fortune from the railroad business to make the initial large donation to establish the Berkshire Athenaeum on Park Square in 1876.

It would have been right for citizens to question whether the tariff that Shaw voted for was in the country’s best interests or Shaw’s. Likewise, it’s a legitimate question to ask if Allen was serving the people of Missouri in promoting the construction of railroads or his own business interests. Examples like these led to laws enacted as early as the Civil War making it a crime “for Members of Congress and Officers of the Government of the United States from Taking Considerations for Procuring Contracts, Office or Place from the United States.” Civil service reform followed in 1883 and, the law that set up the Office of Government Ethics was passed in 1978 in the wake of Watergate when public confidence in the integrity of government dipped to all-time lows. The new law laid out the rules and penalties relating to financial disclosure, acceptance of gifts, outside earned income and post-government employment, among others.

Massachusetts passed its first conflict of interest law fifteen years before the federal law governing state and municipal employees. Once the federal law was passed though, Massachusetts set up its own ethics commission and added a financial disclosure requirement for political candidates and state employees in "major policy-making positions."

Our incoming president-elect is legally correct in stating that the 1978 federal law exempted the president and vice-president from the conflict of interest requirements. That exemption had more to do with concerns over restricting the president’s ability to have the full range of options in the course of carrying out his duties.

The legal exemption, though, is not the same as Donald Trump’s claim that “a President can’t have a conflict of interest.” Being “legally exempt” is not the kind of statement that builds public confidence in its government and institutions. The line is blurred between his vast empire of business holdings and the decisions he will have to make on tax reform or foreign relations with countries where he conducts business. Former White House Counsel C. Boyden Gray (a Republican) agrees that “presidents should conduct themselves as if conflict of interest laws apply to them.” He was elected, after all, with a promise to “drain the swamp” in Washington, so he really needs to start by leading by example.

Over the next few years, the public will undoubtedly learn more than it ever imagined about the intricacies of conflict of interest law, picking up terms like “nepotism” and “emoluments.” Unless, of course, the incoming president takes the steps needed to ensure the line between his personal assets and the public interest is not blurred. That’s the wall he should build.

It’s what every public servant does.