The Appalling Echo this Historian Hears in Trump’s Rebuke to the Media

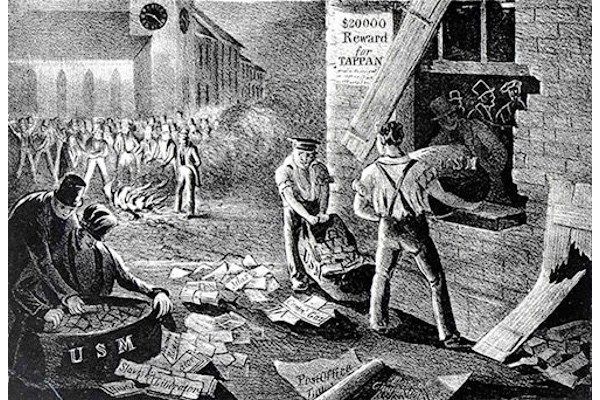

Charleston, South Carolina post office raided by a pro-slavery mob, July 1835

The Trump Administration’s early efforts to undermine facts and journalists it finds objectionable has struck many critics as an un-American assault on First Amendment freedoms. Though the White House’s attempt to denigrate our free press seems to contradict cherished American values, our history shows that powerful governmental forces have often feared a free, fair, and factual dialogue. McCarthy-era witch hunts or the post-World War I Red Scare come to mind. But the best American precedent of denying disagreeable facts and muffling free speech and freedom of the press is undoubtedly the undemocratic anti-abolitionist actions of nineteenth-century slaveholders and their northern political allies.

By the 1830s, proslavery ideologues

asserted that slavery was a “positive good” beneficial to white

and black Southerners alike and refused to tolerate any open national

discussion of the facts of American slavery as it was. When

slaveholders insisted that Congress completely ignore petitions

requesting even modest antislavery legislation, the House passed nine

years of gag rules that automatically rejected the pleas of hundreds

of thousands of petitioners.

By the 1830s, proslavery ideologues

asserted that slavery was a “positive good” beneficial to white

and black Southerners alike and refused to tolerate any open national

discussion of the facts of American slavery as it was. When

slaveholders insisted that Congress completely ignore petitions

requesting even modest antislavery legislation, the House passed nine

years of gag rules that automatically rejected the pleas of hundreds

of thousands of petitioners.

When abolitionists sought to make their case directly to the South – with perhaps the first modern direct mail campaign – slaveholders demanded the right to tamper with US mail. After slaveholding president Andrew Jackson failed to secure legislation authorizing postal censorship, his slaveholding postmaster general simply looked the other way as southern (and some northern) subordinates broke federal law by removing unwelcome publications.

Southern congressmen and state governments even urged new laws to criminalize the printing of antislavery newspapers in the North; no northern state legislature obliged, but in much of the South freedom of the press only went so far as the media remained loyal to slavery. Southern politicians claimed that such restrictions would shield the American people from the schemes of unpatriotic, dishonest agitators. But slaveholders’ actions manifestly demonstrate their anxiety that in a country committed (at least rhetorically) to freedom, they could not ultimately expect to win an extended, open debate. Of even greater concern for many slave masters was the fear that antislavery publications would encourage enslaved people to resist more forcefully.

So proslavery politicians trampled First Amendment principles as they demanded silence and threatened violence. For example, in 1848, after a failed escape attempt by dozens of Washington, D. C. slaves (including people owned by the sitting secretary of the treasury and former first lady Dolley Madison), a proslavery mob gathered to menace the Washington offices of the nation’s leading antislavery newspaper. When New Hampshire’s antislavery senator John P. Hale proposed legislation to restrain future anti-abolitionist rioting in the District, a Mississippi colleague warned that if Hale ever entered the Magnolia State, “He would grace one of the tallest trees of the forest, with a rope around his neck, with the approbation of every virtuous and patriotic citizen.” Hale retorted that if his senatorial adversary was to visit “some of the dark corners of New Hampshire,” he “would find that the people” there “should be very happy to listen to his arguments and engage in an intellectual conflict with him, in which the truth might be elicited.”

Abolitionists and their antislavery allies in the capital craved open discussion and celebrated the give and take that is essential to public discourse in a genuine democracy. Abolitionists believed that if they could share widely enough the facts of slavery’s atrocities—like those recounted in autobiographical “slave narratives” written by the likes of Frederick Douglass, Solomon Northup, or Harriet Jacobs—Americans would be forced to face the contradiction between the Declaration of Independence’s premise that “all men are created equal” and the fact that at any given time between that Declaration’s drafting and the onset of the Civil War, an eighth to a fifth of all Americans were legally “things,” permanently unequal, owned as someone else’s wealth.

But the southern slaveholding minority would tolerate no such discussion. And because of their extraordinary political power within their states and thus within the major national political parties, southern masters found non-slaveholding allies who, for political, economic, or racial reasons, endorsed the suppression of antislavery publications. But in the process politically mobilized abolitionist activists discovered that their voices were not muted but amplified. Now they spoke not just on behalf of enslaved black Southerners but also as the champions of First Amendment freedoms for white northerners. In fighting for freedom of speech and freedom of the press, abolitionists made ever more convincing their claims that southern slavery was fundamentally at odds with American freedom and that the proslavery political establishment’s disregard for white liberty in the North directly connected to the far more extreme denial of black liberty in the South.

So, as we observe the current administration’s efforts to discredit the concept of a free press and an open discussion of verifiable facts, we should be mindful of our history. If Trump Administration officials believe they can advance their policy agenda on its merits, they would be wise to welcome a free and fair “marketplace of ideas.”

If the Trump White House instead seeks, like nineteenth-century proslavery politicians, to secure undemocratic objectives by muzzling unpleasant or disagreeable arguments and facts, then we would do well to remember that those who would speak truth to power can be even more effective when they can stand as champions of the basic freedoms to which our Constitution entitles us all, including those with whom we disagree.