Davos Cosmopolitanism Is Under Attack. But Were the 19th Century Cosmopolitans Like Richard Burton Role Models?

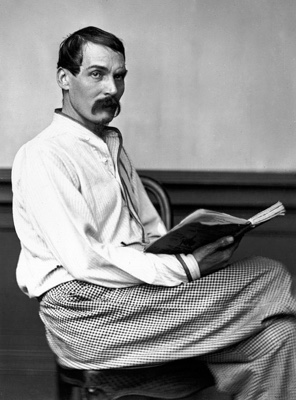

Sir Richard Francis Burton (1821 - 1890)

Capturing an undercurrent of imperial nostalgia in the wake of Brexit and Trump, conservative commentators have gone so far as to invoke Rudyard Kipling, T.E. Lawrence and the Victorian explorer Richard Burton as genuine cosmopolitans in contrast to today’s metropolitan elites. In the aftermath of the election, as a campaign admits that it deployed prejudices because they played well, they may not intuit how apropos a choice Burton proves in an era of post-truth.

For

Burton the cosmopolitan was himself the stuff of a (self-styled)

myth. At a moment when the gut feeling of truthiness gives way to a

conscious disregard for facts, Burton, who was equal parts genius and

conman, may well resonate. He was the consummate purveyor of tall

tales and biases for those seeking to escape the enlightenment of the

metropole.

For

Burton the cosmopolitan was himself the stuff of a (self-styled)

myth. At a moment when the gut feeling of truthiness gives way to a

conscious disregard for facts, Burton, who was equal parts genius and

conman, may well resonate. He was the consummate purveyor of tall

tales and biases for those seeking to escape the enlightenment of the

metropole.

Burton famously sought the source of the Nile and explored forbidden destinations from Mecca to Harrar. The maddening thing about him is that for all his accomplishments, he insisted in claiming ever more fantastical feats. Burton aced exams in a half dozen languages during his service in the British East India Company in the 1840s, but would claim mastery of two dozen more, including Arabic, which he did not pass, and Sanskrit, which he may not have studied. Burton could pass for a Muslim, or at least play the part, but he also claimed to have been initiated into secret rites as a Hindu Brahmin, and to have become a dervish who performed feats of divination. Little wonder he is reborn in countless fictionalizations and biographies.

Burton became a counter-cultural hero in Bohemian circles for the unwelcome truths he brought back to London from the wider world about Britain’s delusions of imperial grandeur and the folly of its civilizing mission. These truths he stuffed into his prolific travelogues, literary excursions, and infamous commentary to the Arabian Nights. But is cosmopolitanism the right word to describe the outrage with which he sought to challenge assumptions and inhibitions of London society? Giving offence was his thing. Burton, spinner of tales, spoke untruth to power.

Burton was well aware of the power his reputation for worldly travel and experience gave him over his interlocutors. Burton understood that his legend was his greatest strength. He welcomed rumors that he had committed every cardinal sin, killed a boy en route to Mecca, and tasted strange flesh in the kingdom of Dahomey. Presiding over discussions of phallic worship and homosexuality at meetings of his Cannibal Club in a restaurant at Leicester Square, he flaunted every taboo.

There is perhaps much for the liberal and the postmodern to admire in the Victorian explorer. Burton believed all claims to truth to be constructions, the product of particular histories and cultures. This was manifest in a curiosity and empathy for different forms of belief, notably Islam and Mormonism. And Burton is remembered by gay rights activists as a pioneer, having sketched a global history of homosexuality in an appendix to his Arabian Nights in an act of defiance against its criminalization in England in 1885.

Yet much of Burton’s counter-cultural appeal to his contemporaries lay in his political incorrectness. At his least sympathetic, in his travelogues of Central Africa, Burton sometimes presents a (non)WestWorld, a playground where the adventurer could break taboos with impunity. (Burton is the hero of that other 1970s fable of sex, violence, and reincarnation—Riverworld).

If Burton seems to have abandoned the worst of his stereotypes of Black Africans over time, this only highlights the callousness with which he was willing to trot them out to enliven his Arabian Nights commentary. In need of copy, and shielding his plagiarism from earlier translators, Burton recycled the most outrageous tidbits of prejudice from his traveler’s notebooks, whether he still believed them or not.

Burton is indeed a cosmopolitan for our (post-truth) era.

Yet perhaps the relevant political lesson here is that the labor of working through cultural difference is not the preserve of a league of extraordinary gentlemen. It is the work of a wider range of actors, not only among but outside the global elite, including the local language teachers, guides and interpreters who facilitate the cultural immersion and self-actualization of cosmopolites like Burton, both then and now. As the movement of such figures into Europe, the UK and the United States is further curtailed, this is a good moment to uncover their stories—in which an important truth of cosmopolitanism from the margins may lie.