Cries of Violating the Logan Act Are Frequent

Michael Flynn

The resignation of General Michael Flynn over revelations that he had misled the White House about an improper conversation with the Russian ambassador has caused a furor and raised more questions about the relationship between Trump administration figures and Russia.

One conversation Flynn had with

Russian Ambassador Sergey Kislyak

occurred the same day the Obama administration issued

new economic sanctions against Russia for allegedly meddling in the

U.S. presidential election. Initially, Flynn denied they discussed

the sanctions, but later admitted they had.

One conversation Flynn had with

Russian Ambassador Sergey Kislyak

occurred the same day the Obama administration issued

new economic sanctions against Russia for allegedly meddling in the

U.S. presidential election. Initially, Flynn denied they discussed

the sanctions, but later admitted they had.

Flynn’s actions, taken before President Trump’s inauguration, have been interpreted as a violation of the Logan Act. This broad law was passed at the very end of the eighteenth century and named for George Logan, a Quaker physician and farmer from Pennsylvania who was highly esteemed by Thomas Jefferson. During the undeclared naval war between the U.S. and France in 1798-99, Logan went to France to try to broker a peace. The Federalists in Congress—Jefferson’s political foes--subsequently passed the law that prohibits a private citizen from engaging in diplomacy with a foreign government that has a dispute with the United States.

The specter of the Logan Act has been raised numerous times since 1799, yet there has been only one indictment under the law—of a Kentucky newspaper—and no convictions. Among those who have been accused of violating it are the Rev. Jesse Jackson, Rep. Nancy Pelosi, Rep. John Boehner and even Trump himself, when he appeared during his campaign to be urging the Russian hackers to find Hillary Clinton’s “missing” emails. It has often been used by the party out of power to sling arrows at the party in power.

Trump isn’t the first president-in-waiting to deal with a trigger-happy emissary. So did President-elect Franklin Delano Roosevelt during the 1932-33 interregnum. The emissary was a man named William Christian Bullitt.

Bullitt had been a diplomat in the Wilson administration and one of the youngest members of the delegation that went to France to negotiate the Treaty of Versailles. Wilson sent him on a secret mission to Russia, where he met with Vladimir Lenin, and returned urging the president to recognize the Bolshevik government. Wilson declined. Deeply disillusioned by that experience, Bullitt left the State Department and lived in Europe throughout the 1920s, marrying (and divorcing) the widow of American communist John Reed.

Seeking to return to diplomatic work, he met with FDR shortly after his election in 1932 and offered to visit European leaders, at his own expense, and discuss the outstanding war debt owed to the United States. The debts were tremendous—Great Britain owed $4.5 billion, France owed $3.9 billion and Russia’s debt was estimated at $75 million or more. (That amounts to more than $148 billion in current dollars.) An installment was due on Dec. 15 and there was great concern that the European players would default.

Bullitt met with Ramsay MacDonald, the prime minister of Great Britain, French Premier Edouard Herriot and the German foreign minister, sending messages in code to Roosevelt via a third party. He returned to the United States before Christmas and briefed the president-elect in person. Nothing was settled on the war debt question, but Bullitt did gather a good bit of information that Roosevelt’s secretary of state-designate Cordell Hull deemed “interesting and useful.”

He did make one major miscalculation. “Hitler is finished,” he declared, “—not as an agitator or as leader of an aggressive minority, but as a possible dictator.” One month later, Hitler was named chancellor, and after that his rise was unstoppable.

Roosevelt, who would not take office until March 4, was so pleased that he dispatched Bullitt on another round of visits in January. This time he communicated directly to Roosevelt via FDR’s private secretary, Marguerite LeHand. Unfortunately, word leaked out about the trip. Damaging headlines appeared such as “Roosevelt ‘Secret Agent’ is Reported in London.” Indiana Senator Joe Robinson demanded, “Who is this man Bullitt?... I think the State Department should immediately apprehend him.” Roosevelt, a bit shamefaced, denied that Bullitt was his emissary.

Bullitt cut his trip short and returned to the United States in mid-February with his collar turned up and a hat pulled low over his face, hiding out in a friend’s apartment for several days. However, he was never indicted, and other than a jeer directed at him by Louisiana Senator Huey Long—“Damn near sent you to jail for twenty years, hey, boy?”—that was that. Why did Bullitt survive his Logan Act escapade while Flynn did not?

The biggest reason was that the country was facing such major crises during Bullitt’s time that no one could pay attention to minor ones for long. The banking system was headed off a cliff, with close to 3,000 banks failing in the first months of the year. Unemployment had reached 25 percent. Finally, on February 15, the day before Bullitt’s return, there was an assassination attempt on FDR’s life in Miami.

By the time Bullitt began lobbying hard for a position at the State Department in the spring of 1933, Congress was immersed in passing major pieces of New Deal legislation, as well as partially repealing Prohibition. The actions of one freelance diplomat, which had never yielded any results, good or bad, were easily forgotten. Also, unlike Trump and Flynn, there had been no suspicion about Roosevelt and Bullitt having inappropriate ties with government leaders in Europe.

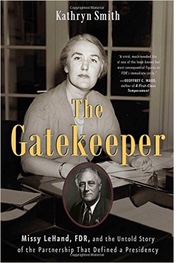

Bullitt’s diplomatic experience and, in particular, his insider’s knowledge about post-revolutionary Russia, won him an appointment with the State Department in May 1933. (It probably didn’t hurt that Bullitt had some powerful people in his court, including Raymond Moley, the chief member of the Brain Trust, and Missy LeHand, with whom he soon embarked on a long-term romance.) In late 1933 he became the first U.S. ambassador to the Soviet Union. He later served with distinction as ambassador to France.

As for George Logan, the man for whom the Logan Act was named, he was elected U.S. senator from Pennsylvania in 1800 and served six years in the Congress that had sought to punish him.