There’s One Last Big-Ticket Item on Trump’s Agenda: A War on Drugs

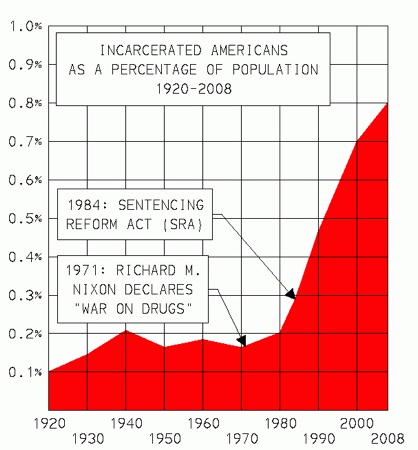

Graph demonstrating increases in United States incarceration rate

The weeks since Trump took office with a pledge to make America wealthy/safe/proud/great again have been tumultuous ones. He has tested the nation’s checks and balances with a series of aggressive executive actions and abrupt policy shifts, on everything from the border wall, the structure of the National Security Council, immigration, attacks on the judiciary, and the selection of Cabinet appointees diametrically opposed to the mission of the agency they are intended to lead.

None of these moves are truly intended to increase the efficiency of national policy. Trump is, if nothing else, a master of branding and his policy moves have been largely symbolic; he’s sending a message about his values and his vision for the United States.

But hang on, because there is more to come and, aside from jobs, there’s still one big ticket item on his to-do list: drugs.

The threat posed by drugs was a consistent theme during the campaign and often lumped with immigration, globalization, and violent crime as part of a rising lawlessness that threatens the American people. Trump reiterated this theme in his apocalyptic inaugural address, pitting “the forgotten men and women of our country” against foreign enemies who drain jobs and wealth and replace them with poverty, crime, gangs, and drugs—all under the watch of political elites who did nothing to stop the “American carnage.” Never mind that Trump is also something of a robber baron and never mind his myriad conflicts of interest, this style of rhetoric says: look there—that is the enemy, the other.

Students of America’s many drug wars have been watching these developments with real trepidation, because we’ve heard this message before. The drug war has always fed on social and political turmoil and functioned as a way to consolidate both political authority and a largely moral and intolerant brand of American identity. In short, it’s not a question of if Trump will declare war on drugs but when.

And, in fact, the opening shots have already been fired. Trump has promised a return to “law and order” to a gathering of police chiefs and sworn to be “ruthless” in taking the “fight to the drug cartels.” The day after he made these remarks, Trump welcomed Alabama Senator Jeff Sessions as his new Attorney General and used the occasion to sign three new executive orders: instructing the Department of Justice to aggressively prosecute crimes against law enforcement officers, create a new Task Force on Crime Reduction and Public Safety, and increase interagency efforts to combat international drug traffickers.

While Trump’s talk of criminal cartels “destroying the blood of our youth” smacks of racial hygiene and fascism, the drug war has essentially always been understood in terms that link biology, morality, and identity. Like many of Trump’s policies, the fight against drugs packs a big symbolic punch. Richard Nixon and Ronald Reagan, the presidents most closely associated with the war on drugs, both rendered the conflict in similar fashion and for similar reasons. Nixon described drug addiction as “a problem which afflicts both the body and the soul of America,” and Reagan, while urging Americans to “Just Say No,” called drug abuse “a repudiation of everything America is.”

The country’s struggle with drugs has a much longer history than most people realize, with roots that stretch well over 100 years into the past. From early U.S. concern over opium addiction in China and the colonial Philippines, the establishment of the first federal control laws, into the beginnings of global enforcement at mid-century, and throughout the presidencies of Nixon and Reagan, American drug policy has consistently turned on issues of symbolic—rather than scientific—importance. Questions about the hazards and benefits of globalization, the role of the U.S. in the world, national security, nature vs. nurture, race and crime, the social contract, and—most importantly—American identity have proven far more determinative than the pharmacology of drugs or the particulars of any given drug epidemic. Many of these tensions continue to define American political culture today.

With the drug problem historically framed in cultural and ideological terms, control and enforcement strategy have focused almost exclusively on punitive policing and supply-side solutions. Rather than rely on comparatively “soft” public health strategies to reduce demand, American policymakers have demonstrated a clear preference for going after bad guys—like foreign traffickers, street-level dealers, and deviant junkies. Despite its obvious practical shortcomings, this adversarial drug war framework prevails because it skirts internal responsibility for the drug problem; drugs are a scourge perpetrated against the American people by outside powers, rather than a domestic social problem tied to America’s own internal contradictions and predilections. And one of the consequences is that we overlooked the risk posed by the growth of the legal narcotics industry.

The American Society of Addiction Medicine estimates that in 2015—the most recent year for which there is good data—around two million Americans suffered from a substance abuse disorder involving opioids. Of those, nearly 600,000 were active heroin users, and four out of five new heroin users began with a prescription opioid. That same year, the number of deaths specifically attributed to heroin overdose (12,989) eclipsed the number attributed to gun violence (12,979). In short, the problem is growing and its causes have more to do with legal practice and industry than criminal trafficking.

According to data provided by the Center for Disease Control, the rates of opioid prescription and overdose have both quadrupled since the start of the millennium, and the influx of legal opioids has created new heroin markets throughout the country. Ironically, the problem is particularly concentrated among older, white, working class populations in areas like the Rust Belt, Appalachia and the Deep South—the same areas that turned out in strength for Trump in November. Broadening the scope beyond opioids, the National Institute on Drug Abuse estimates that the collective abuse of alcohol, tobacco, and illicit drugs is a $700 billion a year problem.

The question is: what is Trump going to do about it?

In his most direct remarks on the campaign trail, Trump acknowledged the need for expanded treatment options, but he also promised a return to the punitive and supply-side strategies that have done demonstrably little to solve the drug problem, including the use of mandatory minimum sentencing and a general escalation of street-level enforcement. And, of course, he also promised a wall, telling his supporters, “A wall will not only keep out dangerous cartels and criminals, but it will also keep out the drugs and heroin poisoning our youth.” The actual efficacy or viability of the wall remains very much in doubt, even within Trump’s own party. But that’s also beside the point; the wall—much like the Muslim/travel ban—is a gesture that signifies a besieged nation in need of a strongman to lead it.

Trump’s willful conflation of illegal immigration and the drug problem is no real surprise. Trump, after all, first seized political relevancy by casting doubt on the citizenship of Barack Obama, and his great ally in the birtherism conspiracy was ex-DEA agent Joe Arpaio, who drew national attention by proclaiming himself “America’s toughest sheriff” and fulminating against illegal immigration as the source of all of America’s problems. (Arpaio is still at the birther thing, by the way.) The notion that Obama is not a U.S. citizen is a proven falsehood, but the rhetoric and cultural beliefs the conspiracy signaled clearly played with that segment of the electorate dismayed by the election of America’s first black president.

A major indicator of Trump’s intentions comes from his selection of Sessions as Attorney General. This is a man who was deemed too racist to win a federal judgeship in 1986 and once joked that he thought the KKK was ok but for their pot use, so it’s unlikely that Sessions will prioritize a healthy respect for civil rights over Trump’s calls for aggressive drug enforcement. Indeed, Sessions has reportedly been a determinative influence on Trump’s hard-line positions and – as White House Press Secretary recently indicated – is likely to pursue a confrontational approach with the twenty-nine states that have voted to legalize marijuana, setting up yet another potential constitutional crisis.

It’s all but certain that Mexico will be a primary antagonist in any Trump drug war. When Trump declared his candidacy for office, he did so with the charge that Mexico actively exports drugs, crime, and rapists to the United States. Within days of entering the White House, he caused yet another controversy with joking/not-joking remarks about sending the U.S. military to deal with Mexico’s “bad hombres.”

China, another campaign trail punching bag, will also play an important role on the foreign policy side. China has long been the world’s largest supplier of synthetic drugs—including fentanyl, a powerful narcotic implicated in recent spikes in overdose rates. But China also seems to be cracking down on illicit production and is an area where the DEA has been making notable progress with quiet diplomacy instead of more confrontational tactics.

On the domestic front, the major policy decisions revolve around policing vs. treatment. Trump has already threatened to send the feds into Chicago to quell the city’s gun violence, but it’s doubtful he’s going to send the feds into places like Alabama, Tennessee, Ohio, West Virginia, and Hew Hampshire—states that have some of the highest densities of opiates and the highest rates of overdose.

The ostensible “whitening” of heroin is a real dilemma for the Trump administration. It’s always been difficult for the authorities to parse the difference between dealer and user, and Trump is probably not going to wage drug war on his own voters. But expanding treatment options is going to be terribly difficult in the face of GOP plans to dismantle the Affordable Care Act, which extended new coverage for drug and alcohol disorders. It also remains to be seen if Trump is willing to confront Big Pharma in the same manner that he has rattled his Twitter account at General Motors and Boeing.

The biggest uncertainty looming over all of this, however, is figuring out how much is bluster and how much of Trump’s tough talk signals actual changes in policy. The DEA has acquired wide-ranging law enforcement authority in its nearly 45-year history, both at home and abroad. Even as a mere rhetorical device shorn of any real policy shifts, the drug war is a source of power and it’s likely only a matter of time before Trump attempts to claim it. We’ll know more when the first report of the newly created Task Force on Crime Reduction and Public Safety is published four months from now.

The most likely scenario is that Trump will mostly ignore the specifics of the opioid epidemic and stick with the supply-side enforcement tactics that appeal to his bombastic and adversarial style. To address demand is to admit weakness, and, in Trump’s worldview (such as anyone can know it), the “forgotten people” need jobs, not coddling or rehab. Instead, Trump will use the drug issue to reinforce his basic theme of a blighted America that begs for decisive leadership. He will focus on urban gang violence (which has a limited connection to the opioid crisis), double-down on his confrontation with Mexico, and use legal pot and China’s role as synthetic supplier as pawns in his gamesmanship to extract economic concessions from the states and foreign rivals.

That’s a best-case scenario. All bets are off if Trump embraces the mantle of drug warrior with the enthusiasm of Reagan. And all the while, the drug crisis and the injustices of the American police and legal system will almost certainly grow worse.

There is, however, one glimmer of hope. Trump will be the first to tell you that he’s a great deal maker; now that we’ve seen the “whitening” of heroin perhaps he will seize the opportunity that lies before him and strike a grand bargain that moves national policy toward a more effective balance between law enforcement and the humane treatment of American addiction. But I wouldn’t hold my breath.